This article accompanies the presentation of Alexei Shulgin's Form Art as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Alexei Shulgin was one of the most popular and influential members of the notorious net.art “movement” of the nineties. If net art (without the period) is a diffuse field of practice, net.art (stylized with the period) was more like an artistic avant-garde, attracting a fluid group of artists who shared antiestablishment politics and an interest in creating new social and artistic contexts through the internet. Shulgin was part of this group from its beginnings in the mid-1990s when German artist and activist Pit Schultz organized a group show in Berlin in 1995 entitled net.art, including artists such as Vuk Cosic and Heath Bunting. Form Art was one of Shulgin's most visual works from this period.

Known for his sense of humor and his clever art interventions, Shulgin acted as a net.art intermediary. He showed other artists (like Olia Lialina) the internet, built context with projects like Introduction to net.art (an online text written together with the artist Natalie Bookchin), and even sowed confusion with his prank mail "Net.Art—the origin," sent to the nettime mailing list, an important forum for the discussion of early net art and culture. In that email, he claimed that the term net.art, stylized with the period, had been lifted by Vuk Cosic from a garbled email. The latter is one of only a few highly persistent myths in net art history, and it is entirely false.

Alexei Shulgin's 1997 performance Cyberknowledge for Real People marked a turn in my own thinking about net.art. For that project, he handed out printed collections of critical texts, previously distributed only online, to shoppers in Vienna. This showed that net.art was not medium specific at all, which until then was the predominant theory; it did not have to be experienced online. After the turbulent transformative period of the net.art death declarations at the turn of the millennium, Shulgin organized several influential software art festivals, as well as the online software art repository runme.org with the media theorist Olga Goriunova and with active contribution from media artists Alex McLean and Amy Alexander. For the past few years Alexei Shulgin has been part of the Electroboutique collaborative, with Aristarkh Chernyshev, spending most of his time in Moscow.

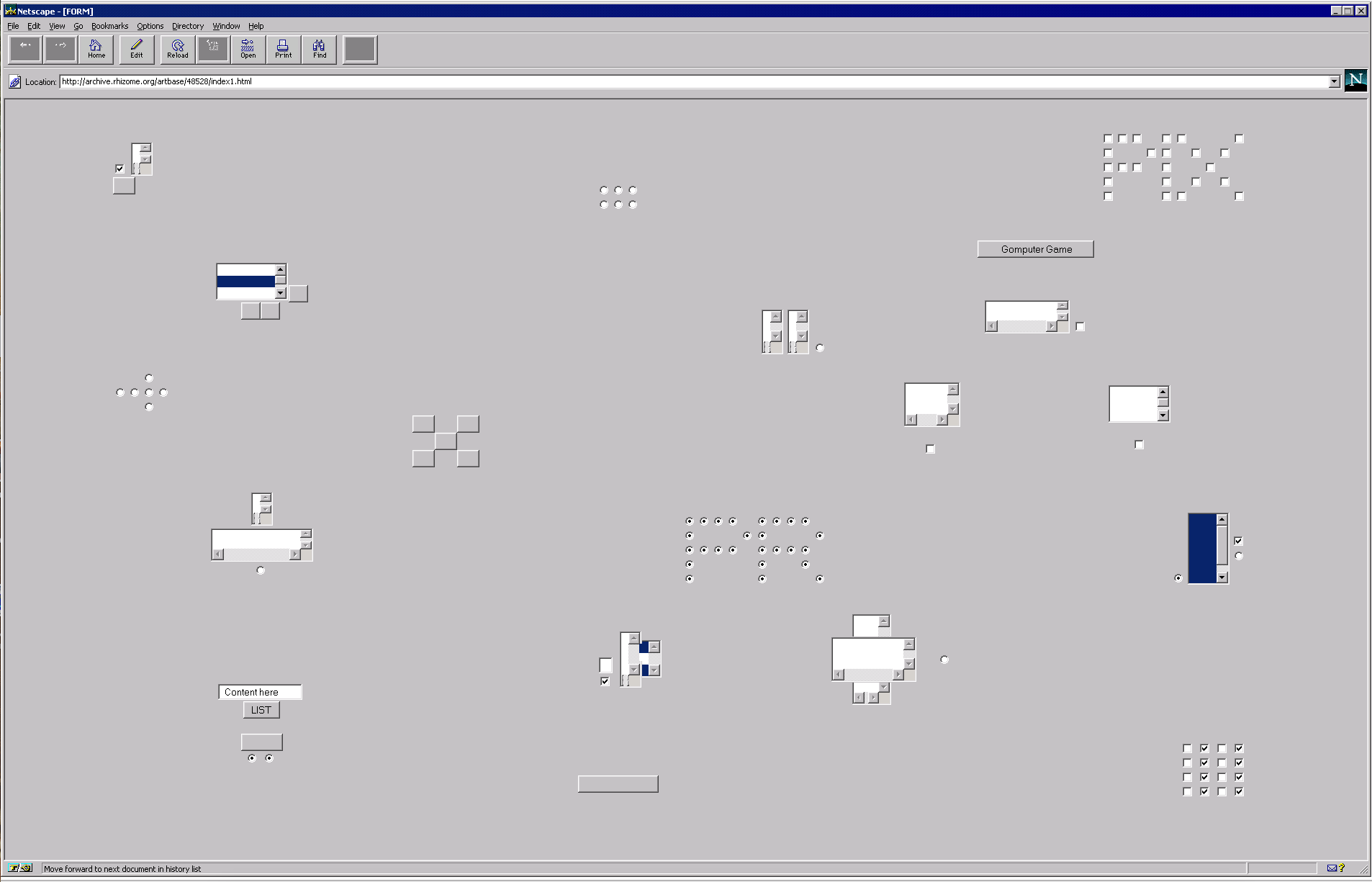

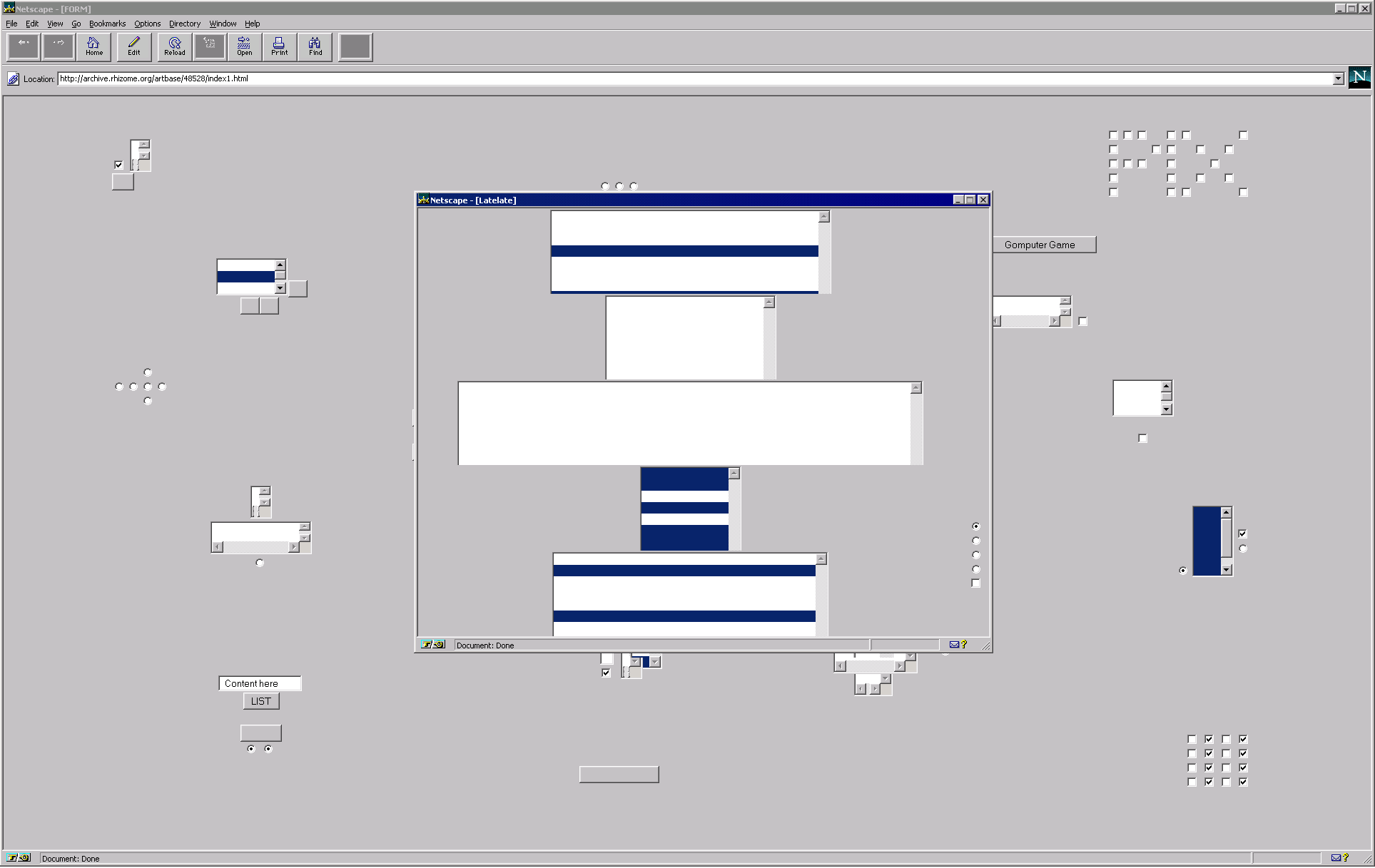

Alexei Shulgin's Form Art seems an odd duck in his oeuvre. It is at first glance a purely formalist experiment with web “forms,” the buttons and boxes that were used as click-and-select interface objects in web pages. Form Art however quickly became a niche art form with a short-lived but dedicated cult following, much like spam art and ASCII video. Form Art made a lasting impression because of its simplicity in shape and color (all grey), making it emblematic for early web aesthetics, and because of Shulgin's success in turning Form Art into another communal net.art open work. What makes Form Art so appealing is how its near-brutal modernist aesthetic relates to the visual overload of the web. Form Art accidentally managed to build a bridge between the avant-gardes of both the beginning and the end of the twentieth century.

What follows is an interview between Alexei Shulgin and me, conducted via email in January 2017.

Josephine Bosma: Form Art was one of many experiments you did with the internet. How do you look back on it?

Alexei Shulgin: It has become one of the most popular of my net projects of that time. This was probably because it focused on the (for that time) new aesthetics of the web interface. I made it during a residency at C3 in Budapest in May 1997. The C3 residency was a great opportunity—the perfect conditions for working on this project, for which I had already quite a clear idea of what I wanted to do. The idea to do a formalist project like Form Art came after I went through a period of jealousy towards Jodi, who were so great in doing that.

I had those buttons, test areas, checkboxes in my mind for a while. The initial idea was to use them not as they were supposed to be used—as input interfaces—but to focus on their shapes, their position on a page, and to try to animate them. Think: “Misuse of technology,” absurdist mega-interfaces. Bringing them in focus was a declaration of the fact that a computer interface is not a “transparent” invisible layer to be taken for granted, but something that defines the way we are forced to work and even think. And that it is made by the technology developers.

Alexei Shulgin, Form Art, seen via Netscape 3.04 in oldweb.today

JB: How do you see Form Art in relation to your other works?

AS: As a “net artist” I don’t think I had any particular style. In the 1990s it was so exciting to play around with the internet—exploring both its aesthetic and communication aspects. More than that, I was absolutely sure that art after the internet would never be the same and that from now on an artist does not need to play traditional career games, including maintaining his or her own style. I was open to any idea about the internet as an artistic medium or as a channel for art distribution that could have come to mind. From the perspective of today, one might say I was a rather experimental net artist.

JB: Are you saying that Form Art was just one experiment among other experiments you did?

AS: I was interested in various aspects of the internet: collaboration, communication, crowdsourcing, data search and data mining, context mixing. I was not very consistent in what I was doing. Form Art, as I said, was a research in form, but it was also followed by the Form Art Competition that was announced in the framework of Ars Electronica (AE). It was an act of parasiting on AE's symbolic capital. AE is known for its competition and its main art award, Prix Ars Electronica. This award was being criticized for not being objective and there were complaints that the jury members didn’t even look at the submissions. So, instead of this “corrupt” competition I decided to organize a “fair” one.

JB: How did the Form Art Competition go?

AS: By that time I was the only expert in the new art form that was Form Art. So, naturally, I appointed myself as the only jury member. I announced the prize—1000 dollars. That was a risky move: by the time of the announcement I didn’t have the budget confirmed (in the end AE paid my winners). To make long story short—I had a few dozen submissions. That was a surprise! Some submissions were very complex and smart. It was exciting that so many people took the idea and made something. And of course that was thanks to the power of the internet, which delivered the information to them. Basically, I organized the international competition on my own with the help of mailing lists, AE’s symbolic capital, and a small budget. I selected two winners and one honorary mention.

JB: Is it your only non-collaborative work?

AS: In a way this one was collaboration as well. I worked on it together with Laszlo Valko, who did valuable JavaScript coding work. I asked C3 for some JavaScript support and they introduced me to him. He was quite young but already the author of a thick book on programming. It was a great pleasure working with him. Ususally, it takes time to deliver an art concept to a coder. They wouldn't understand right away if something non-pragmatical, like blinking radio-buttons or self-scrolling pages, should be developed. Luckily, Laszlo and I had great understanding between ourselves. Unfortunately, I have never seen him since the project has ended.

And then, after I developed the core principles of Form Art I of course announced the competition, where other artists could submit their Form Art projects. And they did!

JB: What would Form Art in the year 2017 look like? Would it be possible to make it at all?

AS: I don’t think it would be possible today, because those input interface elements of a browser I was playing with have now lost their distinctive shapes. They now appear in thousands of shapes created by web designers, and therefore don’t manifest any new aesthetics. New aesthetics today come from things like neural networks, so nowadays we have a young net artist named Google.

JB: You don't really answer my question on how you look back on it, how you see it from today's perspective.

AS: Well I think I said something on that when I was saying how exciting it was to work on the project. In general, now I am having mixed feelings about early net art because I see how the strategies developed by net artists are now used by corporations and in politics. But that's the destiny of avantgarde art—developing communication and aesthetic tools for the future capitalists and politicians.