The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Elizaveta Shneyderman: Your work Porn Interventions complicates the user relationship to virtual imagery. Instead of the free flow of sexualized bodies, as you describe, users are confronted with something far more critical and strange. By melding both an affective and physical understanding of bodies on the screen, the work deconstructs the trope emerging out of a construction itself. In general with your work, you notice a blip in technology’s capacity to destabilize and you render visible that network of assumptions behind it. Beyond gendered interventions of technology and technofeminist fetishization, could you speak to this interest of conflating technology with identity? Do you consider exposing the methodology of a medium an inherently feminist act?

Faith Holland: I’m part of the first generation that grew up online. I did a tremendous amount of identity building. And because technology and the web have been rapidly changing (beginning with semi-private access to AOL around 1995), I’ve done it over and over again. From carefully composed AOL profiles that maxed out available character counts and alternating capitalization (like the origin of my most enduring handle, aSuGaRHiGh) to the creation of purposefully esoteric interests and mood-defining avatars on LiveJournal, to the endless process of defining oneself on Facebook, representing myself online is a life-long project.

The identity building I started to do online coincided perfectly with the onset of puberty. The performance of gender was always an obvious element of socializing on the web, even more obvious at that time than socializing off screen. So, while I don’t think deconstructing the functionality of technology is inherently feminist (if only!), that was always and inevitably going to be part of my interpretation because it was so deeply ingrained in those early experiences. For me, it’s been really fruitful to go back and think about those experiences alongside the prevailing post-body ideologies of the early web. When I think about technology—then and now—it’s steeped in bodies: the bodies that want to know a/s/l, the bodies visualized and circulating, the bodies that are tapping and caressing in their interaction with the screen.

Faith Holland, Woven Network in Lube (2013)

ES: I am wondering whether it’s possible to address the contemporaneous tendency to turn all matters of language into signification. In your video Artist Statement, you begin to scrawl “My art subverts representations of…” before quickly rescinding and reverting. Do you think language is afforded too much power? Is there something to be gained of the ineffable?

FH: Language is extremely powerful and not to be underestimated. But it also exists to be subverted and manipulated, and thus rightfully deserves scrutiny. Thinking about this post-election, I wonder if the web has helped us to critique and improve language. I’m thinking specifically of all the rallying against ‘alt right’ as a dangerous, deceptive euphemism for neo-Nazi. Or the increasing usage of the singular ‘they’ as a gender-neutral term.

Artist Statement, funnily, is the oldest piece on mine on my website and the oldest that I still show with any frequency. It’s a parody of art-world speak, as I had just entered graduate school when I made it and was immersed in the problem of how and what to communicate, in written language and images. Accessibility is important to me as an artist; my work would ideally be legible and hold meaning to any audience who would care to engage with it. At the same time, my work is research-based and conceptual; I want there to be depth for those who are willing to take the time to plumb it. So, I have increasingly moved toward accessible imagery and language that points toward deeper issues. In short, I always try to make my work function on multiple levels: one of immediate engagement and one that rewards further thinking. All of the projects on my website include some kind of description that hopefully makes my intentions decodable without closing down meaning—and there’s always more there that I don’t grasp, but others might. One of my projects, VVVVVV, includes a bibliography of research about pornography, histories of the web, and feminist theory, which I’ve continued to draw from for all subsequent work. It might be time to do an extended version, actually. I often receive emails asking for additional research materials related to my work.

The ineffable is maybe a driving factor in making images—how can we think through words, feelings, ideas, and phenomena visually? The translation to the visual is always imperfect and therefore always feeds new work.

Surfing the Void, from VVVVVV (2012)

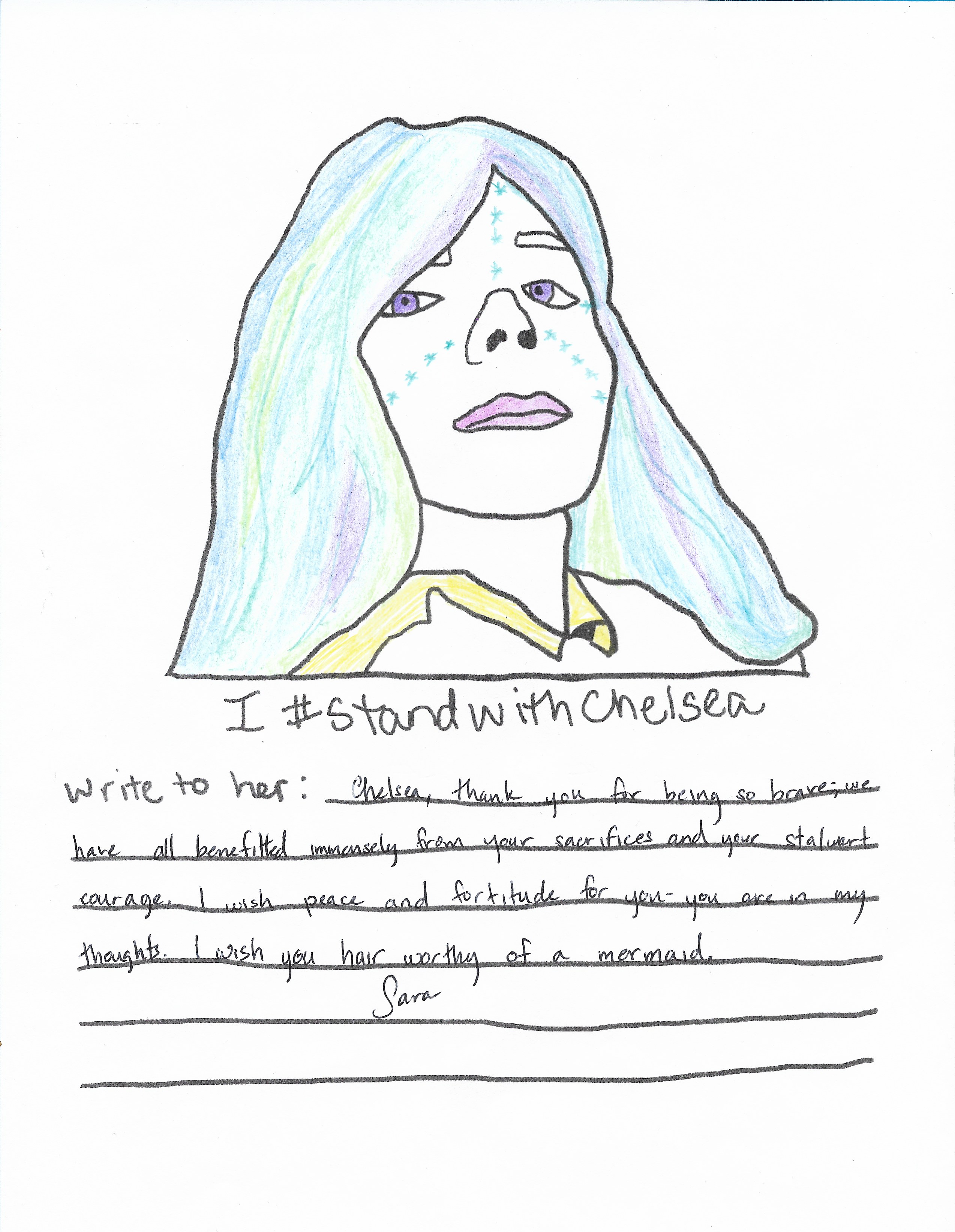

ES: You are well versed in vernacular clickbait. Much of your work—I am thinking of Porn Interventions in particular—is site-specific to a screen, existing willfully on platforms that provide them their necessary context. I really enjoy that #SaveChelseaManning diverges from this model, and involves ongoing action and activism from you. Could you speak more about your relationship to the body off-screen?

FH: #SaveChelseaManning was different in a few ways—it was also a collaboration with poet Sara Jane Stoner, who wrote a piece and performed it the first time the work was shown. Most of what I made for that project were GIFs, Chelsea Manning Fan Art, but it was important that the work not only be about Chelsea, but for her. So I wanted to give everyone an easy means to participate and make something for Chelsea that could be sent to her directly in the mail. I also mailed her still images from each of the GIFs.

#SaveChelseaManning, Pelican Bomb installation (2016)

In regards to the off-screen body, what occupies a lot of my thinking is the place where the body meets the screen—the touchscreen. This went from futuristic to commonplace in a nanosecond at some point in the late aughts and continues to be a subject of fascination for me. What happens when conduits seemingly disappear—like mouses and keyboards—and we appear to be interacting more directly with the screen? Screens are more bodily than ever; we touch them all day, they hug our bodies in our pockets, they recognize our bodies’ imprints, we sleep next to them at night so that we can reach for them first thing in the morning. In my work I like to think beyond these intimate everyday interactions towards exaggerated gestures that draw attention to the behaviors we’re already engaging in.

And I couldn’t fully think through this issue of physicality and the digital without physical works. So my practice inevitably moved more towards sculpture and installation. I also just have a strong desire to pour lube on wires and other technologies!

ES: What’s behind your motivation to enact the web culture of the 1990s? What is the continued role of nostalgia for net artists, if any? Can you talk about your inclination towards this (analog, pixelated, glitch) aesthetic sensibility?

FH: Looking back at the 90s remains important because the distribution of power on the web was, for that brief moment, totally different than it is today. Early web users were much more engaged in generating form, whereas now there are so many services that predefine forms and only allow us to generate content (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, RedTube, and others—the list is very long). So the user-generated aesthetics of that time are remarkably different from the ones we’re currently used to now that corporations are always framing our content. Recalling those ‘nostalgic’ aesthetics is, for me, an attempt to reclaim or re-assert a need for that kind of user-control and user-creation that can exist outside of corporate walled gardens.

ES: What does a “radical,” female-gendered project look like these days?

FH: Radical is a tricky word and one that I don’t necessarily care to use. For me, interesting work being made in the name of feminism is not necessarily radical, but rather addresses fairly simple and fundamental problems like intersectionality (which, to think once again about the power of language and technology, my spellcheck doesn’t recognize) and thinking harder than just leveraging socially acceptable feminine (white, cis, skinny, etc.) bodies. To me, those intersectional issues shouldn’t be considered ‘radical’ but they remain underrepresented, as the same artistic formulas of ‘art by women’ get replayed over and over again.

Questionnaire

Age: 31

Location: New York

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I grew up around computers. I remember having a program on our first computer before the age of 5 that I would run from a floppy and could ‘color’ (it was a monochrome screen) different pictures, especially dinosaurs. Then I would print them out—it was a hybrid digital analog process. But I really got into art through photography, starting with a digital camera, moving into film, and then coming back around to digital late as a graduate student.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I studied Media Studies at Vassar College. That’s where I first started to think about pornography seriously. Then, after a gap, I did my MFA at the School of Visual Arts in the Photography, Video, and Related Media department. I moved through the program title quite literally—photography, video, and then “related”—in that order.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I love to teach and can sometimes make money that way, but never enough to sustain myself. I also do and have done: copywriting, photo/video production, social media management, bookkeeping, arts administration, and basically anything else that comes my way. Finding work seems to always occupy my time.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)

Header Image: Faith Holland, Queer Connections (2016)