This essay accompanies the presentation of Mongrel's BlackLash as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

At the turn of the millennium and even earlier, games had a much greater impact on American culture than contemporary art. Unlike other mediums, games have an interactive dimension that allows for deep affective investment. No surprise then that at the horizon of gaming’s figurative puberty, artists were playing with the medium: among others, there was Manetas’s Flames (1997), Thomson and Craighead’s Space Invaders-format meditation on authorship Trigger Happy (1998), Natalie Bookchin’s Borges adaption Intruder (1999), Dutch collective JODI’s disorienting, minimalist Wolfenstein 3D mod SOD (1999), and British collective Mongrel’s BlackLash (1998). This latter work was particularly important for its repudiation of utopian virtuality, examining the specific context of gaming and its prominent stereotyping of blackness.

1998 marked a horizon of vast potential for gaming: in the sixth console generation, technological advancements allowed for more realistic graphics, and the astronomic rise of game sales broadened the market, ushering in a shift in focus toward teen and adult gamers rather than kids. The hacker ethos of the 1980s was merging with gaming culture, evidenced by modding communities for games like Half-Life (1998) and the beginnings of a now-flourishing indie game market. Nintendo’s family-friendly grip on the industry had loosened, allowing new players like Sony and Microsoft to step in and begin establishing their own gaming empires.

However, these developments did not address the problems of earlier gaming ideology, leading to the new horizon — in many cases — simply replicating these issues. For example, the early waves of gaming in the US were predominantly white: white male developers created white male characters for presumed white male players. Avatars of color only appeared as stereotypes and punching bags. Orpheus Hanley, a black American composer and sound designer who worked at Midway Games, describes the situation: “In the 80's and 90's you never saw black characters. If there were black ones, they would get beat up, really whumped so fast, before they had time to get into character.”1

Taking cues from modding aesthetics of the time but with an eye toward the historical precedents of the new horizon of gaming, the British collective Mongrel2 inverted the paradigm Hanley describes with their 1998 Macintosh game, BlackLash. Instead of making black characters bear the brunt of physical violence, the game features a black protagonist doling out the attacks against a variety of antiblack aggressors. BlackLash finds the slippage between the “hood” and the “information superhighway,” excavating the market-driven stereotyping of blackness in gaming and virtuality to “battle the forces of evil that plot to convict or eliminate you from the streets.”3

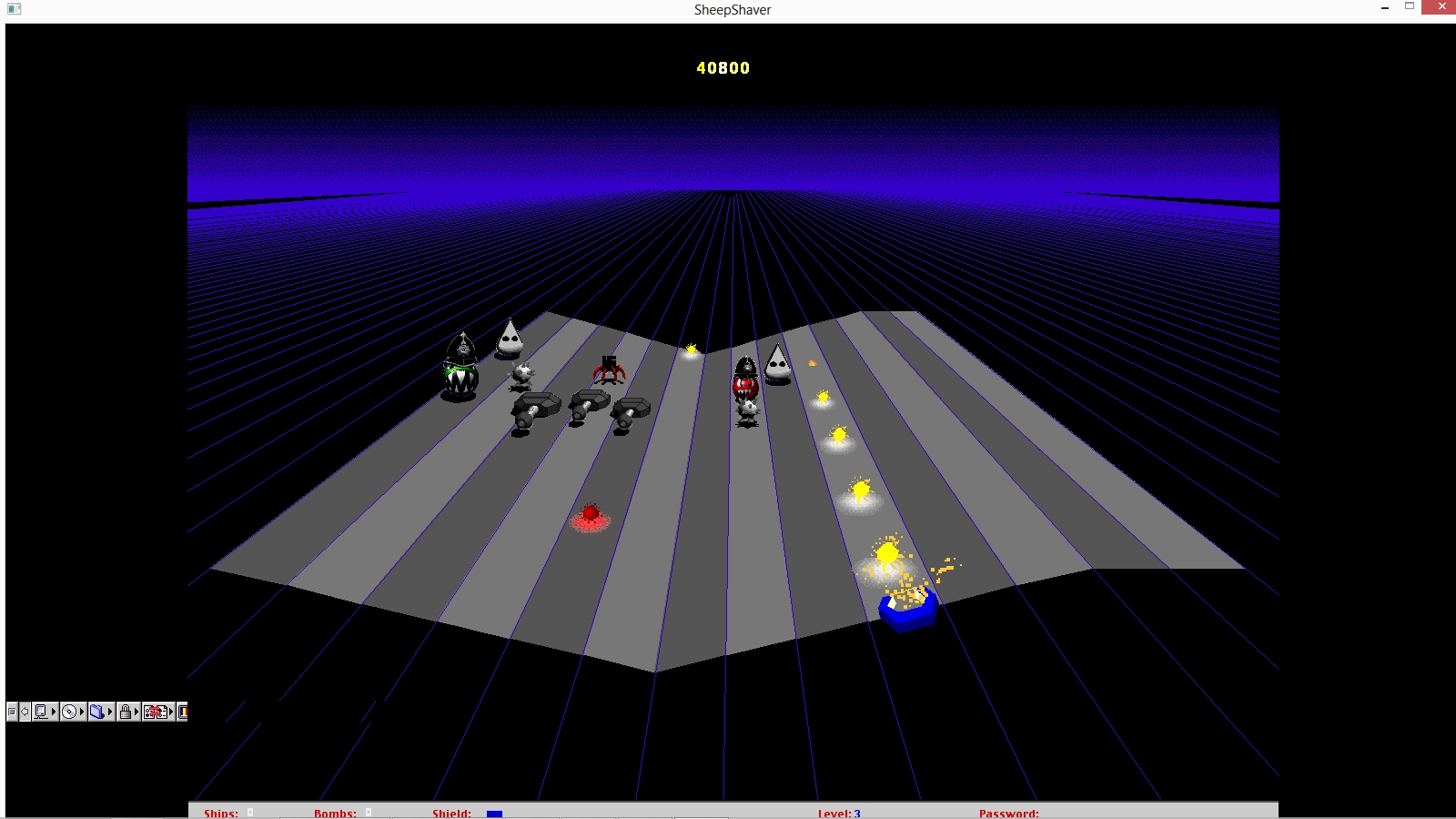

screenshot from BlackLash.

Working from 1995-2008, Mongrel worked to fuse “a challenge to the conception of cybercultures as ‘race neutral’ with a corresponding refusal of the contemporary invocation of a multiculturalism-beyond-conflict.”4 Through sardonic irony, unauthorized software modification, hacktivism, false corporations, and other forms of culture jamming, the group pilloried the hegemonic ideologies of post-Thatcher Britain and celebrated “the methods of an 'ignorant' and 'filthy' London street culture.”5 In vernacular aesthetics they saw not only the potential for greater reach but deeper critique. Their foray into gaming was no different: Mongrel member Richard Pierre-Davis states that Mongrel “hacked another game and created a game called BlackLash…I was fed up with companies making black games with no relation to black people whatsoever.”6

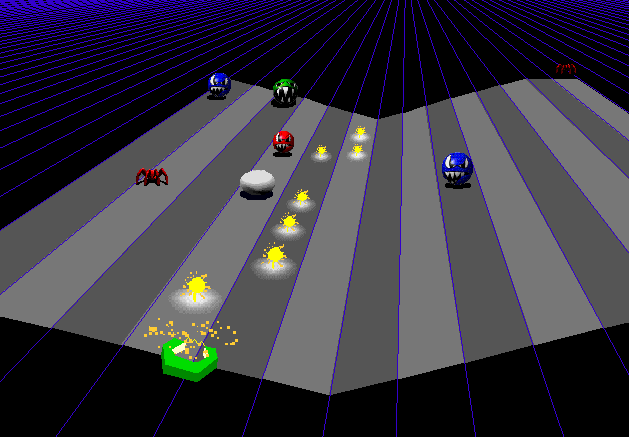

Released for Macintosh in 1998, BlackLash is a mod of a 1995 Mac game called Macattack in which you maneuver a spaceship in various pseudo-3D planes divided into lanes, shooting enemies to score as many points and survive as long as possible. In BlackLash, the spaceship is replaced with four black stereotypes as playing options: professional, crime-lord, lover, dry-cleaner. Enemy ships become “white wigged judges, cops, hypodermic needles, Ku-Klux-Klan heads, Nazi spiders,”7 and others with roles in the oppression and violence against black people. Dated 7 November 2070, the game copy states:

“The filth is still in command of society and the streets, making sure only the selected few can escape the shit hole. The authorities have unleashed their law enforcers to crack down on the undesirables and maintain control of the streets contaminating all areas with guns and drugs. Here is your chance to kick some arse and annihilate the powers that be and smack them into the next millennium."

The game also features a presumably appropriated Wu-Tang Clan soundtrack.

The author losing on level 1 with 2350 points.

Like some other examples of videogame art at the time, BlackLash foregoes 3D realism, instead sourcing a title that was already ancient in gaming terms. Not only does this properly situate modding culture in an older, originary hacker ethos; by juxtaposing earlier gaming aesthetics with the heavily stereotyped nonwhite characters in the gaming landscape of 1998, Mongrel suggested a connection between the two which begs exploring. This older focus also ties the new wave of gaming and market-driven stereotyping to the unacknowledged contribution of non-white youth to the early gaming boom: as Greg Tate argues, heavy gameplay by young black and Latino men in late seventies arcades was a direct contributor to the flourishing of the gaming industry.8 If the stereotypes in games in the two decades that followed were some sort of conciliation in light of this, they were a huge failure, and the tech-driven utopianism of turn-of-century gaming simply continued to erase this unacknowledged contribution in the face of an increasingly diverse consumer base.

The earlier-mentioned 1999 article that quotes Hanley—a high-profile New York Times piece by Michel Marriott—frames the time of its writing as a paradigm shift where in the sixth generation of games,

“as a result of a series of rapid developments both technological and sociological, blacks and members of other minorities are being represented in more and more computer games as fully realized characters… In a broad range of new releases like Wu-Tang: Shaolin Style, Urban Chaos, Shadow Man, and Ready 2 Rumble Boxing, nonwhite characters are stars rather than bit players.”9

In Marriott’s understanding, the horizon of greater graphical and conceptual realism also meant a more equitable ecology of visual difference in games.

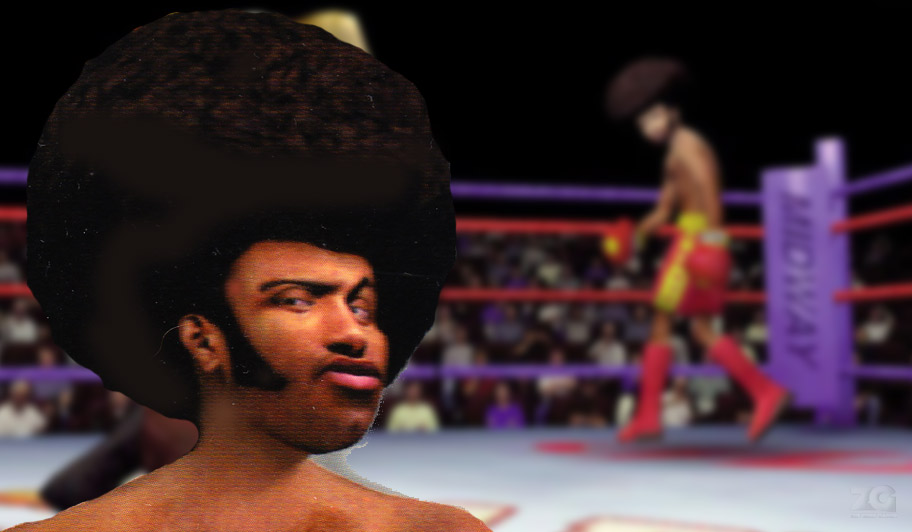

However, in reality nonwhite characters in games at the time continued and exacerbated stereotypes of old gaming, ranging from the comic relief of Ready 2 Rumble’s infamous Afro Thunder—actually modeled on Orpheus Hanley10—to violently absurd, such as the protagonist of Acclaim’s Shadow Man, a black cab driver who has been turned into a “supreme zombie-warrior slave.”11 A 2011 survey of 150 games found that 100% of black male characters were portrayed as either athletic, violent, or both.12 As well, then and now, games generally portrayed women as nubile objects to save, fuck, kill, or fulfill some other “gameplay” function.13

Afro Thunder from Ready 2 Rumble (1999). Image courtesy Midway Games.

Journalist and media executive Adam Clayton Powell III, who at the time was vice president of technology and programming at the Freedom Forum, was quoted in Marriott’s article describing the computer games industry and its prevalence of stereotyped characters as “high-tech blackface.”14 Given that games aspire to profitability, we might conclude, like scholar of digital culture and black cinema Anna Everett, that such high-tech blackface and other encrypted racist and orientalist messaging have a profit motive along with their naturalization of hegemonic ideology.15 These flat black avatars are easy ways to spice up the visual aspect of games for a presumed white audience hungry for ‘safe’ encounters with otherness.

Of course, the problem of “high-tech blackface” will continue as long as game development is primarily white.16 While white developers may sometimes meticulously develop full-fledged nonwhite characters—like the acclaimed half-French, half-Haitian Aveline in Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation (2012), set in 18th-century Louisiana—the critical nuance of lived difference will always escape even most thorough research. Moreover, given the outcry in recent years at games like FIFA 17 featuring a black protagonist17 or survival game Rust randomly assigning race and gender to players,18 it is clear gamers value choice more than difference itself, chafing at being forced to play as non-white, non-male characters. The putatively safe encounter with difference promised by virtual identity flux becomes foreclosed for the white male audience when difference, as it is in reality, is not a costume choice but a random, imposed fact. Likewise, BlackLash—despite its intentions—is not free of the “white touch.”

screen shot from MacAttack.

Indeed, the perpetual forward motion of the game's tubular vector spaces is redolent of the dominant metaphor for the digital at the time: the “information superhighway,” and the enemies embody the insidious ideologies crawling around in it. The game points to the violence hidden in utopian metaphors of seamless connection, speed, and ahistorical globality, as well as the resilience required to navigate this naivete. Even at low difficulty levels, the game does call for some dexterity, particularly due to the KKK enemies: upon being shot or reaching the end of the vector space, each Klan member hatches into two Nazi spiders which land on adjacent columns of the space. At higher difficulty levels, even a slight misstep can lead to an absurd proliferation of Nazi spiders at the screen edge. This speaks to the stickiness of these violent ideologies, which in the game’s universe (and likely in ours) are thriving in 2070.

BlackLash leverages the market logic of stereotypes in the industry to gamify the nightmare deep at the heart of white multiculturalism: black retribution. However, this gamification also points to the fetish for critical black aesthetics in progressive culture. This fear perversely generates a performative identification with blackness to erase one’s complicity in antiblack violence — as Meryl Streep put it when asked about black representation in film, “we’re all Africans.”19 BlackLash also points to the origins of high-tech blackface in older virtual aesthetics. While performative identity morphing was a common aspect of 1990s digital culture,20 the political reality of lived difference was rarely acknowledged, rendering moot whatever idealistic liberatory potential to be claimed in cyber-fluidity. As such, BlackLash seems implicitly aimed toward a white audience, asking it to confront its stereotypes about black men, the marginalized condition of black America, and the mainstream representation of the ‘inner city.’

Despite being billed as “the game the streets have been waiting for,” the necessary affective investment in the stereotypical character options is only really potentially subversive for a white gamer, since for a black gamer this is just another instance of being forced to identify with a stereotype (even a super random one like dry-cleaner). Notably, however, these were not present in the demo version I played, and the promise of these tropes upon payment for the full game is perhaps a wry comment on the commodification of identity. And of course, the potential gratification of shooting the sordid cast of enemies has not aged well in the context of nihilistic sandbox games like the GTA series, where the premise is being able to ‘do whatever you want.’ Nevertheless, BlackLash is an early attempt to inject explicitly political content into a game from either the industry or the art world, presaging the current climate of criticality in both.

We can assume Mongrel could have modded Half-Life to execute the BlackLash concept if they wanted. But the choice to work with a vector graphics game likely made things easier and faster; it also allows the audience to reflect on the ways the supposed development of gaming only replicates its older, originary stereotypes as ostensibly “blacks and members of other minorities are being represented in more and more computer games as fully realized characters.”21 More realistic virtual environments are only a new skin for the same tropes, more and more advances in high-tech blackface.

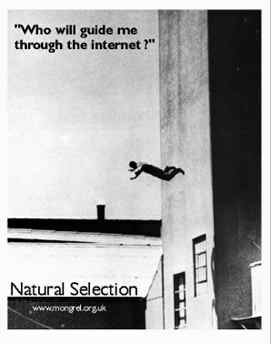

Image from poster advertising Mongrel's Natural Selection (1999), a search engine that illuminated the omnipresence of white supremacist material online. A component of the National Heritage campaign.

The speed of deployment for BlackLash was important because the game was a facet of larger Mongrel projects at the time. With the hacktivist re-education project Natural Selection (1999), Mongrel disrupted various popular search engines such that when users typed in racial slurs, they were directed to a small network of art projects tackling new technologizations of racism, including Mongrel’s own BlackLash and Heritage Gold (1998), Mervin Jarman’s Yardie Immigration Advisor (1998), Hakim Bey’s Islam and Eugenics (1997), and others. Further, Natural Selection was part of an even larger Mongrel project, National Heritage, named after the UK’s arts funding allocation department. National Heritage began in 1997 and consisted of “street poster / newspaper publication, a WWW search engine, and a gallery installation”22 to show the ways that, as Graham Harwood states, “racial dichotomy is the heritage of the nation… and multiculturalism is their excuse for keeping power.”23

BlackLash thus operates both as a standalone product and as a facet of a wider agitprop project using tools of digital and mass media to disseminate anti-hegemonic content. Working in inherently commodified forms like videogames, search engines, and consumer applications, the collective critiqued the ways that putatively radical technologies easily worked in service of national and corporate projects. As well, they embodied the problem of radicality: the necessity of simultaneously imagining alternate worlds and using all available tools, since as Joseph Beuys put it you cannot wait for a tool without blood on it. In all of their projects, Mongrel committed to a refusal to provide easily digestible solutions to the violence of multiracial global capitalism, opting instead to thrust audiences into interactive networked and software experiences to encounter our own investments in the power structure, and maybe even have fun in our self-critique.

Footnotes:

1. Marriott 1999

2. Mongrel was formed around 1995 by Graham Harwood, Matsuko Yokokoji, and Richard Pierre Davis, with Mervin Jarman joining later. Harwood and Yokokoji met at Guildhall University; the others met at Artec, the Arts Technology Centre in London

3. http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/mongrel/home/faqs/ns.htm

4. McGahan 2004: 46

5. Lovink 1998

6. Everett 2001 : 109

7. Nideffer 2003

8. Dery 1994: 209

9. Ibid.

10. Marriott 1999

11. As described by Shadow Man game designer Guy Miller.

12. Burgess et al 2011

13. The extensive work of journalist and media critic Anita Sarkeesian details this well for the contemporary gaming context.

14. Marriott 1999

15. Everett 2001: 124

16. In 2015 the International Game Developers Association found that out of nearly 3,000 surveyed developers only 3% of game developers were black, while 76% were white; 75% of all surveyed were men.

17. https://news.vice.com/article/people-are-mad-they-have-to-play-a-black-character-in-fifa-17

18. http://steamed.kotaku.com/rust-chooses-players-race-for-them-things-get-messy-1693426299

20. McGahan 2004: 9

21. Marriott 1999

22. http://v2.nl/archive/works/national-heritage

23. Lovink 1998

Sources:

Burgess, M. C. R., Dill, K. E., Stermer, S. P., Burgess, S. R., & Brown, B. P. 2011. Playing with prejudice: The prevalence and consequences of racial stereotypes in videogames. Media Psychology 14.3: 289-311.

Dery, Mark (ed). 1994. Flame Wars: The Discourses of Cyberculture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Duggan, Maeve. 2015. Games and Gamers. Pew Research Center.

Everett, Anna. 2001. Digital Diaspora: A Race for Cyberspace. Albany: SUNY Press.

Lovink, Geert. 1998. National Heritage and the Natural Selection Search Engine: Interview with

Harwood and Matsuko of Mongrel (London) {AT} OpenX, Ars Electronica. Nettime.

Marriott, Michel. 1999. Blood, Gore, Sex and Now: Race. The New York Times.

McGahan, Christopher. 2004. Race-ing for Cybercultures: The Performance of Minoritarian Cultural Work as Challenge to Presumptive Whiteness on the Internet. PhD Diss., New York University.

Nideffer, Robert F. 2003. Game Engines as Creative Frameworks. Self-published.