Image: Josh Kline for DIS Images.

The imminent rollback of net neutrality in the United States signals the end of an important, consumer-oriented sort of internet freedom. No longer will companies be prohibited from blocking certain services or websites (so they can then sell access piecemeal in increasingly exorbitant packages), thus solidifying the internet as a privatized, highly classed space.

This is contrary to the ideal of the internet as a great equalizer for all voices, and represents a chilling omen for the so-called “Information Revolution”–the kind of sinister corporate entrenchment the cyberpunks tried in their goofy way to warn us about. But any user who not only shops, but works primarily online has also felt the looming specter of net privatization for a long time—at least as far back as the inception of Web 2.0, when the internet largely took on the shape and character that we recognize today.

As early as 1996 (before the advent of Google), R. U. Sirius, co-founder and former editor-in-chief of cyberpunk magazine Mondo 2000, lamented presciently to journalist Jon Lebkowsky the emptiness of the myth of the internet as some great equalizer, saying:

You’ve basically got the breakdown of nation states into global economies simultaneous with the atomization of individuals or their balkanization into disconnected sub-groups, because digital technology conflates space while decentralizing communication and attention. The result is a clear playing field for a mutating corporate oligarchy, which is what we have. I mean, people think it’s really liberating because the old industrial ruling class has been liquefied and it’s possible for young players to amass extraordinary instant dynasties. But it’s savage and inhuman.

Beneath a small cadre of very well-paid columnists and other assorted nepotism cases exists an overflowing morass of labor supply–writers, editors, artists and so on who are trying to make use of the internet for professional purposes, but who in many cases lack both the capital and networking ability to springboard their small online hustles into sustainable careers. Meanwhile, large sections of the internet have been carved out and wholly controlled by major corporations and crowdsourcing and marketplace platforms. The virtual land is farmed for content, from which platform holders skim off profit in exchange for use of the platform. Of course, this results in a general funnelling of profit upward, away from the people actually creating most of the content.

Outside of a shrinking elite, this class of artisans and intellectuals has only become more proletarianized over time. This will only get worse the more endowments and other forms of public arts funding dry up, the more austerity and gentrification immiserate people’s living conditions, and the more companies are able to get away with exploiting the labor of online workers for laughably small payouts. It has always been difficult for people outside the more privileged classes to hack it as artists and intellectuals, but the break with tradition that the internet was originally believed to represent has now given way to a form of virtual feudalism.

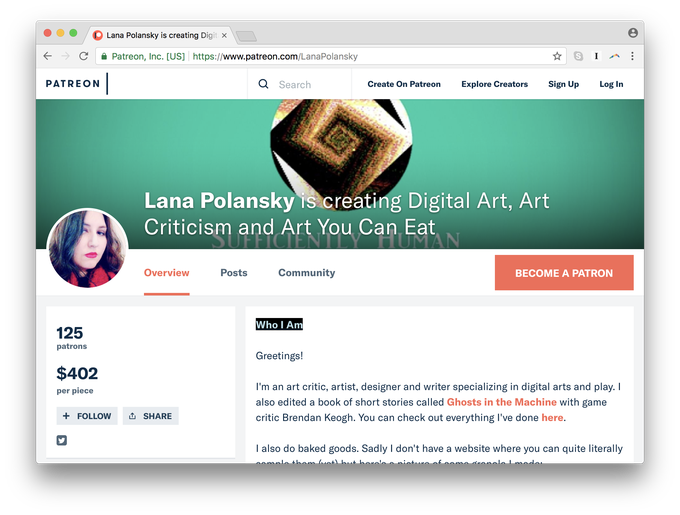

These circumstances have set the table for sites like Patreon to brand themselves as a savior-like market solution for independent, often struggling artists. Before I go any further, I must admit that I use it. In fact, at this moment it accounts for most of my income (the rest is supplemented by contract gigs such like the one that produced this article.) Many friends and peers also have Patreon pages, sometimes as a complement to profiles on other platforms like Etsy or Redbubble. Maybe they’ve run the odd Indiegogo campaign to get their independent film project off the ground. Maybe all that wasn’t enough, especially in an emergency, so bereft of savings they were forced to use GoFundMe or YouCaring to help them pay for amenities or take the edge off a steep medical bill. The main distinction between Patreon and other sites resides in the fact that Patreon is designed to offer a regular subscription service, meaning it offers an appealing consistency compared to other sites.

Like many people, I have a love-hate (increasingly, just hate) relationship with Patreon. I know exactly how I’m being exploited and yet, without this platform I have no idea how I’d manage a steady, monthly income in my line of work. I make a middling but comfortable amount thanks to Patreon subscriptions that allows me to maintain my personal site, and gives me the stability to seek out other work at a more reasonable pace. Contract gigs like writing for Rhizome only go so far and are replete with exploitative practices all their own; not to mention, of course, the inevitable dry spells. At least Patreon always pays out on the first of the month, just in time for rent. Patreon, much like other crowdfunding-style sites like IndieGoGo or Kickstarter, is relatively easy to use, and offers sellers the opportunity to connect with many more people directly. By bypassing traditional gatekeepers and their usurious percentages, one can (at least in theory) make more money and be subjected to less egregious exploitation.

A few power users have managed to propel themselves to riches and success thanks to Patreon, but these lucky few are in the extreme minority. Many are more likely to bring in a couple hundred bucks a month making games, $60 per piece to make videos or perhaps considerably less–a minimal but still significant sum for people struggling to find any reliable, stable income. In many cases, patrons are also creators, meaning that lower-level earners often use Patreon as a sort of mutual aid service, circulating a small pool of capital from one user to another. This felt like a worthy trade-off with tolerating Patreon’s profit-skimming and its steadily degenerating user interface, but hostile new policy changes threaten to overturn that balance.

Last week, Patreon announced on its blog that it plans to roll out a new payment structure that it promises will allow users to take home a greater share of their earnings–“exactly 95%,” the post claims. What became immediately clear, however, was that this new structure—essentially a regressive tax that passes the “interchange” of processing fees onto patrons, as lawyer, writer and Patreon user Matt Bruenig pointed out–actually only really benefits Patreon itself and a handful of users, while severely undercutting its less successful users.

In general, these platforms turn a profit by charging users a processing fee in exchange for use of the site to sell their wares or receive donations, much like how rentiers charge tenants for use of a physical property. Donation site GoFundMe takes a five per cent cut plus another three per cent in processing fees, while YouCaring only charges for processing. Print-on-demand sites like Redbubble and Society6 set a base price for different items, leaving vendors to set their own markup percentage.

Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, and up until recently, Patreon charge a hefty five per cent (plus credit processing fees) per payment cycle. With this change, however, Patreon still takes its five per cent cut, but instead of pulling a two to ten per cent transaction fee out of the payout total at the end of each payment cycle, now the service plans to take a “2.9% + $0.35” cut out of every individual pledge. This essentially eliminates low-level pledge amounts as viable for many patrons, who often support multiple creators with small pledges, and hits people relying on one dollar pledges especially hard. Even the relatively popular leftist podcast, Delete Your Account, tweeted out a screenshot of all the patrons they have lost since the change, as did short story writer Kameron Hurley.

In an update to the post, Patreon insists that this is not a money-grab for Patreon, and instead argues that it was simply the best way to balance third-party fees with their desire to get their patrons the best payout percentage possible. (One of their examples includes a person complaining that 1K was taken out of their 11K lump sum–an already unthinkably high payout for most people actually using the site.) Self-appointed mediator and popular Patreon creator Jeph Jacques quoted CEO Jack Conte as admitting that they “absolutely fucked up that rollout,” suggesting to many that Conte thinks the problem is how the change was framed, rather than any fundamental issue with the change itself. However, a June 2017 post by tech CEO Brian Balfour that was widely disseminated on Twitter reveals something much more sinister than simple precious ignorance. The piece, entitled “Inside the 6 Hypotheses that Doubled Patreon’s Activation Success,” is mostly business mumbo-jumbo, but a telling quote from product manager Tal Raviv stands out:

"We'd rather have our GMV be made up of fewer, but truly life-changed creators rather than a lot of creators making a few dollars."

In other words, Patreon is actually very comfortable undermining lower earners on a practical and ideological level, even if a few bucks for rent or bills may actually be life-changing to some people. One would think, given its past reliance on a vast pool of content creators for income, that the decision to cull the smaller earners would be out of step with its own profit motive–but to Patreon and its investors, these accounts appear to merely represent a blemish and a hassle.

The payment restructuring policy is a testament to Silicon Valley greed and callous, ignorant flippancy toward the misery of others, all in an effort to disempower a massive and unruly labor pool. And it isn’t only the low earners who face uncertain futures on the platform.

Up until recently, Daniel Cooper wrote for Engadget, Patreon “offered a broad latitude for projects that contained erotic content.” Patreon has also, albeit inconsistently, publicly defended the right of adult creators to make money, going so far as to win a legal battle against PayPal over its refusal to accept transactions for pornographic material. For many online sex workers, this meant that Patreon represented an important, relatively safe niche outside the restrictive and deeply exploitative confines of the billion-dollar porn industry. As sex worker Liara Roux told Samantha Cole for Motherboard, “Yes, we can post on Pornhub, which runs mostly off content stolen from us... Where are our rights? Why should we have to be kicked off every platform again and again?"

They may be kicked off again, though Patreon remains vague on actual policy enforcement. The amended terms of service—which Cooper explains was ostensibly meant to crack down on hate speech and illegal content in light of Patreon’s suspension of far-right “journalist” Lauren Southern’s account—is viewed as a slap in the face by many sex workers, who published an open letter and petition addressed to the site’s CEO. It’s also deeply hypocritical, considering up until recently the platform has historically had no compunction about skimming profit off of published works that directly violate its own TOS, created by people who have in the past attempted to sabotage the livelihoods of other users, most notably during the height of Gamergate.

Yet Conte denies that this will lead to any mass shutdown of accounts. Indeed, Patreon still refuses to actually define what they mean by “pornography” or “adult content”, and remain cagey about how these rules will be enforced in the future. Patreon’s waffling over the years on pornography seems to suggest that it wants to have its cake and eat it too—as part of its new program to protect its image, it wants to appear saintly without taking a real position one way or another. This logic follows the same pattern as the payment restructuring changes. Patreon doesn’t want to lose high-volume creators, but it’s also gambling on the likelihood that it can sacrifice a few—or even many—smaller-time users if it means the site can maintain a positive relationship with investors and influence-peddlers. This means sacrificing sex workers and poorer users while simultaneously attempting to avoid conflict with noncommittal reassurances. This is the logic of a gentrifier.

All of this serves to reveal the great lie at the center of the “gig economy.” The Silicon Valley ideology behind sites like Patreon insists that the “gig economy” is a boon to young creators, where anyone and everyone could be a successful entrepreneur if they just have enough drive and gumption. Supposedly, this is meant to free us from the shackles of traditional employment.

In reality, sites like Patreon thrive off of other people’s work exactly because companies that could employ them opt instead for contracting and outsourcing, which atomizes workers by turning them into direct competitors and rendering them much more exploitable. They generate brand recognition as rebel alternatives by making lots of tempting promises and ensuring ease of use, until ultimately metastasizing into yet another tech monopoly that suddenly needs to gate out the undesirables. And as much as they claim to operate as alternatives, they still need to interact with credit card companies and other payment services, all of which siphon money off of online transactions. These same conditions–the continuing accumulation of power and capital by the few at the expense of the many– are what beckoned the end of net neutrality even as the corporate web was still taking shape. It’s also what explains the backlash against Gothamist and Fusion writers who attempted to organize their workplaces.

The same forces dictate how print-on-demand sites like Society6 can get away with repackaging artists’ work into calendars without ever paying those creators a dime. Meanwhile, numerous craftspeople who use these sites to sell their designs have accused major fashion retailers like Zara and H&M of stealing their work. This isn’t much different from sex workers or journalists seeking alternatives to going underpaid, getting plagiarized or robbed of compensation, or being denied opportunities, only to have the sites offering those opportunities squeeze profit out of them.

At their most sordid, online funding platforms have found a profitable niche in healthcare funding—or to pay for other essentials like rent or groceries. Money-raising sites in general rely on power users who can go viral, but donation sites take that logic to its cruelest conclusion. “Virality” is hard to achieve for a sex worker or a podcaster, but it’s an inhumane demand on the sick and poor that could only exist in an inhumane society. As Anne Helen Peterson wrote in “The Real Peril of Crowdfunding Health Care,” “That doesn’t mean we should stop giving. But it does mean we should stop mistaking stopping a leak for fixing the plumbing.”

Yes, sites like Patreon can buoy up individuals who otherwise might have to risk destitution or quit their craft, but the entire economic apparatus that enables their existence also guarantees that they will earn less over time, on platforms that offer none of the guarantees or benefits that real employment can. The same old gatekeepers are still very much in place, and Patreon relies on the same old meritocratic fantasy that we could all be in that place too, with hard work and the power of positivity.

The only response to the problem of charity crowdfunding is socialized healthcare, much like the only solution to the end of net neutrality is to nationalize the internet and treat it like a public utility. Likewise, “content creation” workers are forced to rediscover the power of organizing, while recognizing a shared struggle not just with other exploited “gig economy” workers like Uber and Amazon drivers, but with workers writ large. Where this can’t manifest in traditional workplace organizing, genuine mutual aid and cooperative, creator-owned funding tools could represent an actual alternative. Patreon, like every other feudal lordship on the internet, is filling a void in society that was put there by design. By design, we can also get rid of it.