This interview accompanies the presentation of Hell in Lamb UC as part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Pedro Vélez, Hell in Lamb UC, 2003-2007

Simone Krug: How did Hell in Lamb UC start? What was the impetus?

Pedro Vélez: I wanted to use MySpace as a platform to create a narrative about Hunter S. Thompson's book, The Rum Diary. I also took characters from the other stuff that I was making in 2001-2003 and applied these characters and ideas in a freeform narrative about the book.

I've always been interested in journalism, so it had to do with whether the facts presented in the book were facts or not. The MySpace piece was a way to debunk the idea that Hunter S. Thompson spent more than six months in Puerto Rico. It was also about the idea of the colonizer exploiting the island and its resources to write his own book of fantasies and how he could get away with it.

SK: Hell in Lamb UC was both the name of the broader project and also the name of one of the four fictional characters in the MySpace work. You had four different accounts and you created this narrative in which different individuals would communicate with one another so that it became a theatrical, almost staged play taking place on the internet. Could you expand on how the project worked?

PV: I tried to have these four fictional characters on MySpace talk to each other via each other's walls. When you read the text they were like riddles. You had to figure out what they were trying to say. I had four different email accounts with different pictures to produce each profile. I had to log into one account, post whatever I needed to post, close that email, go to the next email, and then post other information.

SK: What was appealing to you about MySpace as a platform compared to what else was available, like Livejournal or Facebook (accessed only by users with an @edu account at the time)? Was it MySpace’s ubiquity and popularity?

PV: It was easy to use. You could post any type of image or video. I was making photographs and posters that had a specific look that MySpace’s aesthetic was close to. It was also very gossipy. People wouldn’t write on a wall, it was just a journal where you wrote personal stuff. I found that idea of a personal journal that everybody could look at interesting. I was interested in the voyeuristic interface.

I had previously worked online in collaboration with other people during the very slow dial-up era. You would send an email or you would write on a message board, and somebody would send me an image to post on our fan zine online, and it would take three hours to upload. And then the text took another day. I used MySpace as a tool because it was really fast. I liked the immediacy. Within journalism, you knew it was going to change the idea of writing. I thought about how those platforms could develop, or how they could be useful for what I was trying to do as an artist.

SK: Did Hell in Lamb UC belong to a larger body of work that you were making at the time? Or ideas about social media performance that you were thinking about then or think about today as an artist?

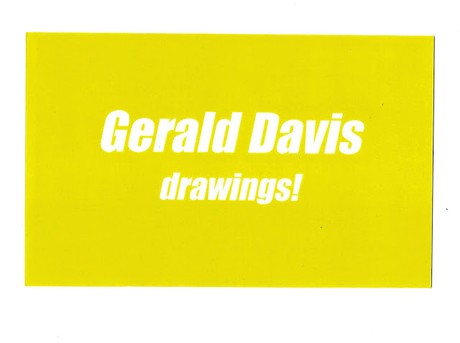

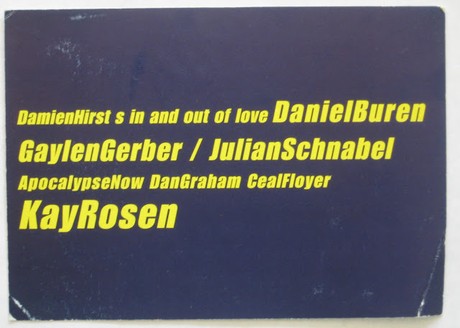

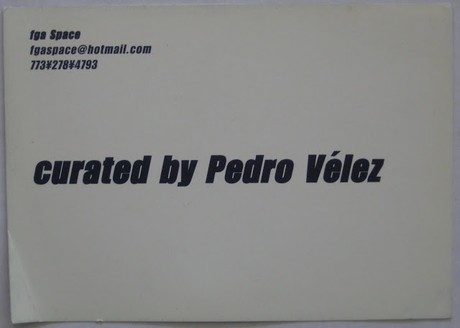

PV: Around 1997-1999 I made fake TV shows I called Fake Shows. There were invitations for events that only existed on a postcard with an email, no address. But that was limited and I wanted to reach a wider audience. Then things like MySpace came along and then I was looking for free access to a platform to exploit those ideas in a larger context. It was all related. In 2001 I also curated an online show for Gerald Davis hosted on GeoCities. These were drawings made for this one particular show, which took a week to set up because it was still dial-up. I had somebody writing the code because I'm not a computer whiz. We would also go to this message board page for criticism in Chicago called the FGA. As technology got better and you could upload stuff faster, it evolved rather quickly. It was a natural progression. I also distributed soundtracks and sound shows through the internet.

Postcard for “Drawings,” online exhibition hosted on Geocities (2000).

Postcard for a Fake Show, 1999. Limited edition of 3,000 distributed freely in 1999 with the economic support of John T. Belk

SK: Like the flyers for the fake art shows and the performances, the idea of fiction—playing with ideas that are real and not real, seems instrumental in your work. You’ve also called Hell in Lamb UC a “faux over faux” multimedia piece. Could you tell me more about the main characters—Hell in Lamb UC, Ann Lee, Staged Metal Party, and Hunter S. Thompson (sometimes called "Hunter God FS").

PV: Hunter Thompson was the writer but instead of Thompson it's just God. It's a joke but it also comes from Godfuck. I think I heard that in a movie. The whole idea of Ann Lee as a character was in response to Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huygue’s Ann Lee project. I came up with Staged Metal Party because I did this party at my place in Condado in San Juan every Friday where I would ask guests if they would allow me to take photographs. We would make flyers, but the idea was to photograph people having fun and partying, not wasted.

SK: There was this particular party aesthetic in the mid and early 2000s when digital cameras became smaller and people were able to photograph the party scene. I’m familiar with these images from New York and Los Angeles. Were you working along those lines within the same aesthetic?

PV: Yes, but in my work this wasn’t straightforward, there was a lot of sarcasm. So when you look at the Staged Metal Party page, you'll see that I adjusted the colors of the MySpace page to the colors in the photograph. And at the time I used this tiny Sony camera. The Staged Metal Party character also had to do with glam metal band Ratt member Robin Crosby, who died of an overdose but also had AIDS. I tried to portray the hangover of the party as a guilt trip about his death. Heavy metal was over. It was a different era. I tried to depict that washed out feeling of those ’80s bands and the excess and decadence but then also the feeling of sadness. My parties were never really about having a perfectly good time. I tried to include politics in that character.

SK: What about Hell in Lamb UC? Where does that name come from?

PV: In my cultural context on the island of Puerto Rico, the lamb represents us as a people, colonized by the Spaniards and then by the Americans. The idea of innocence, Catholicism, ritual, and the lamb of god. Lamb UC also references college party culture. I've always used the UC or a font which looks like university. I did a show in Miami in 2003 with Hell in Lamb UC as the title. That's also when I used the character Ann Lee for the first time, when I make the comparison to college party culture. And to me the blabber used by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe to justify their purchase and exploitation of the Ann Lee character was easy to deconstruct, which was accepted in the art world like a fact or a fashionable justification for the project. I'm glad I stuck with it because now people have condemned their work.

SK: Many of the images of women in this project are disturbing. What did you use to make these women look like they've been abused and what is the reference?

PV: It's acrylic paint. In Hell in Lamb UC, it refers to Chenault, one of the main characters from The Rum Diary who is raped and abducted by a guy from the island. The protagonist, who I'll guess is Hunter, suffers for a few pages but doesn't really care or try to find her. For him she was a hassle. Chenault is the alter ego or the subconscious voice of Ann Lee within those two characters on the MySpace page.

SK: How does this work exactly?

PV: One character already has the experience of being abducted and exploited and she tries to tell Ann Lee. The way I see it, she's almost like a therapist. But we're speaking about art. I cannot give you a clear, concise idea of what I was trying to do because I'm pretty sure I wasn't even aware of what we were trying to do half of the time.

SK: Did you get feedback in which people had specific issues with these pieces? Obviously these images of abuse are disturbing. Did people push back against them?

PV: I saw this image of the beat up woman as critique of commercial advertisement and society and their standards of beauty. I understand now and accept that some of it was problematic in the beginning. I did not get much pushback at that time. But also it was because at that time the people who would review my work were mostly men. Those are still the images of straight male desire. It was later on that I was criticized and people asked me questions about this work. Not at the time, though.

SK: But you see them differently with the perspective and distance of time now?

PV: Oh yeah. And I have taken some out of circulation, I have destroyed work of that time which I don't think fit the idea or the critique that I was trying to make. I have removed the ones that are more exposed. Or if the model asked me to not show those images again.

SK: How were these works shown? There's the Hell in Lamb UC poster from 2005 that was a physical, tangible object, but did most people see them from home on MySpace or did you print them out and exhibit them in gallery spaces?

PV: Online it was mostly a gossipy thing. The photographs are from real people who knew other people who posed for the photographs. But a lot of the comments and a lot of the riddles actually led to events or facts. I was commenting on the scene in New York or Puerto Rico so it wasn't all fictional. You have to figure out the riddle.

SK: That's so inscrutable and enigmatic. It's interesting that some of the narratives here reference real events or real things happening in the art world.

PV: I would send announcements every month whenever I would change the content and I worked really hard to have people look at it constantly, to make it go viral.

SK: How would you get people to come to the site?

PV: Send emails, post photographs, send flyers, the basic thing one does to promote a show. But instead of giving you all the information, people would see a photograph of this art dealer sleeping on a bed almost naked. And then you would see that image on one of the characters’ pages, and then things spread like fire. In galleries, I would show the posters. When you see each image on the MySpace page, it’s an actual photo file piece that's not just online. I would make banners, fan zines, and flyers for the exhibitions. We tried to have a computer at the space, but it wasn't personal so I opted to announce the project on a simple flyer on the wall as an art piece and then have people go to the MySpace page instead of setting up the computer in the gallery. That's not the experience that I wanted. I wanted people to interact as if it was gossip.

SK: Could you speak more about being a male in your thirties, an older demographic and age group to be using MySpace at a time when so many people on the platform were teenagers. Was there ever a moment where you felt this age gap or difference and did that have any effect on your work?

PV: I was not on MySpace to produce a personal journal or to cry to the camera. I also needed to adjust certain looks and certain colors and certain ways of speaking to that type of demographic. I wouldn't be able to make a sarcastic or ironic Staged Metal Party profile or persona anymore. I didn't know all the people at the party at the time, but I couldn't do that today. Technology has changed so quickly that I wouldn't have the time to study the aesthetic of new platforms. Right now, I'm interested mostly in politics and the economic downfall of Puerto Rico.

SK: Let's transition and speak more about Ann Lee, the Japanese Anime Ann Lee character which Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno bought the rights to, retired, and then killed. You've made works that argue for her life. This quote is apt: "You cannot kill Ann Lee, she is alive in Puerto Rico. Go fuck yourselves." How did you get involved with that particular narrative?

PV: It had to do with Elián González, the young child who was brought over to the US by his mother who later died and he was abducted by the US government to be returned to Cuba. At the same time these two European artists bought the rights to another child, Ann Lee. These were two children that were put in the public eye, where people made decisions about them. To me that was exploitative, it was also tied to colonization and to race because the macho men are the ones from Latin America, not the European guys. Likewise with Elián González, they are Cuban. His dad wanted him back but this rich Cuban philanthropist living in the US wanted to keep Elián in the US. It was trouble over children between those two different worlds. It was troublesome to me that our politics could determine the lives of certain people, especially in the case of Elián.

I know I'm speaking about Ann Lee as if she is a real person like Elián, although she’s a character. But the art world was invested in it. The issue had to do with morality. As an artist, you participate in society. When I go to my studio, I don't become neutral. I'm always the same person I am in my studio or outside of the studio. So I just simply don’t agree with the fact that artists live in this separate world which is devoid of morality or value or politics. So I would make that connection between those two children.

SK: Honing in on Ann Lee, Heather Warren-Crow writes that you critique the Eurocentrism and neo-colonialism of Huygue and Parreno’s works. And there's obviously the stereotype that she also discusses of white French men buying, animating, and then killing this Japanese Manga girl character, which is a way of silencing her. How did you play with or try to subvert that idea in making her a character in the Hell in Lamb UC MySpace piece? Or do you reject that idea?

PV: When I made the original image of Ann Lee in the poster, I was essentially saying she's on this island in the Caribbean, she's fine. I was creating psychological space for her for people who would look at the piece. I didn't have and I still don't have the economic power to liberate her. But I did have a moral voice back then and I still do. In the end, though I become part of the problem.

That poster, that image will never be sold. For the Whitney piece, it was a reminder going back to my original work, saying Ann Lee is alive and well in Puerto Rico. Now she has a family and here she is. I think the critical discussion about Ann Lee that finally happened a couple years ago that comes from women in the field changes the perspective. At that time it was mostly guys writing in the main media and art magazines. Things have changed and now we have more writers of color, more access, more gender diversity. I think that the battle is going to be won. Not in terms of liberating the idea of Ann Lee or the concept, or taking back those rights. There's a discussion that exists, which didn't have the same visibility ten years ago.

SK: Why do you transform this manga cartoon into a real girl? What's real here and what's supposed to be fake

PV: It's hard to gather. The Ann Lee in the MySpace is not the same Ann Lee from the original photograph of Ann Lee. That's why she might look younger. That was my artistic freedom. That was a decision I had to make because, at that time, the original photograph of Ann Lee was my girlfriend.

SK: Which Ann Lee is which? There’s the Ann Lee Lives picture from 2003, which is a photograph with the text for Huygue and Parreno. And then there's also the Ann Lee character within the Hell in Lamb UC MySpace project, right? And they're different.

PV: They're both supposed to be Ann Lee, but in terms of aesthetic decisions when I made the MySpace piece I couldn’t ask her for permission to use her photograph on the MySpace page. And then the Ann Lee from the Whitney, which is the same Ann Lee from the original photograph, I encountered again about ten years later and then I had permission to photograph her again.

SK: By implicating this character into your work, what were you trying to save her from? And why were you compelled to insert her into the social media, social networking, site of MySpace specifically?

PV:. All these online projects came about because I either wasn't allowed to publish certain writings or because there just wasn’t enough space for me to talk about these things in a magazine. How could people be saying that this Ann Lee was a conceptual masterpiece when there's all these ethical problems with the piece? How come nobody sees that these are two grown men buying a girl, a child? And for people to be claiming that it’s a conceptual masterpiece. MySpace was great to send out signals and S.O.S. For me, it was about justice.

SK: Heather Warren-Crow both praises your Ann Lee work and is critical of it. She writes that for you as well as for Huygue, Parreno, and their collaborators, Ann Lee is understood as a void that is receptive to new narratives. So these two white European men take this character and kill her, but then at the same time you go back and try to save her. What do you make of Warren-Crow’s critique?

PV: I wasn't surprised. Those photographs were stereotypes of certain imagery even though I was trying to be critical. I was trying to critique societal standards, morality and the economics behind the production of propaganda. I don't feel Warren-Crow was unfair, either. I think she made very important observations regarding patriarchy and gender which I couldn’t fully see from my privileged position, that of a young artist, back then, and I have applied and even corrected some of that ignorance in my practice. It was great criticism on her part. But also I think when she wrote the book she didn't get to see its completion in the Whitney and she never experienced my Twitter projects which came after that.

SK: Why did you move away from internet-based work and was Hell in Lamb UC your only foray into what one might call a net-based piece?

PV: I don't stick to one medium. At one point I made conceptual art, and in the beginning I made paintings and did printed ephemera, and then I was a critic for a long time. With the 2014 Whitney show I shut down that chapter of posters and photographs. Now I'm back into painting. And there's different reasons for that, but they have to do with this moment in my career. They have to do with the market. Or what can I produce so I can sell so I can pay the bills. It’s not that I don't love painting,but what I need to say now, in Trump’s era, is better digested with painting.

At the moment I’m working on a series of large paintings that also incorporate photography, dealing with the Jones Act (Merchant Marine Act of the 1920s) which is a regulation imposing punitive fees and taxes to any foreign ships entering our waters and ports. This regulation has been one of the many ills affecting our economic development and was the source of renewed controversy during Trump’s tragic visit to Puerto Rico after María. It is worth noting that my original name in Twitter when it began was Jones District, so we’ve come full circle.