This text accompanies the presentation of Data Diaries as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

“People were listening to nothing but machines. And these machines weren’t playing songs, or anything even remotely narrative, but instead seemed to be playing loops. Simple loops. Loops that seemed to be stuck! Five minutes would pass, and there would hardly be any difference in the music. This was pure, cheap, plastic, battery-powered machine music.” —Cory Arcangel

“We are drawn into the pattern and held inside it, impaled, as it were, on its bristling hooks and spines. This pattern is a mind-trap, we are hooked, and this causes us to relate in a certain way to the artifact which the pattern embellishes.” —Alfred Gell

The background patterns on Cory Arcangel’s Data Diaries website (2003) bristle with hooks and spines. Small sets of grayscale points, repeating endlessly, create patterns that crackle with static. They’ve been gentrified by my retina screen, losing some of their rawness and crunch, but they still catch my mind, transporting me to Liverpool, 2004.

Cory came to Liverpool that year for a residency and exhibition, toting under his arm a giant roll of black-and-white screen prints. They were the leftovers from The Infinite Fill Show, an open-submission exhibition that he and Jamie Arcangel staged at Foxy Production in New York. They invited artists to submit works using the kind of repeating, black-and-white patterns that were used to give a sense of depth on the monochromatic displays of early Macintosh computers.

Remember back when computers couldn’t display colors? Think 1984, 1985,...Back before computers could airbrush, show photos, write emails, or play music they were black and white. To make up for the lack of colors, computers used 16-bit monochrome patterns to fake color. These patterns are called INFINITE FILL PATTERNS!

Infinite, because the computer would repeat them again and again, potentially endlessly. The infinite of infinite fill was the promise of algorithmic automation, of endless repetition with no material cost, at the stroke of a key. Remediating the patterns in analog form involved the opposite: a huge amount of material and labor.

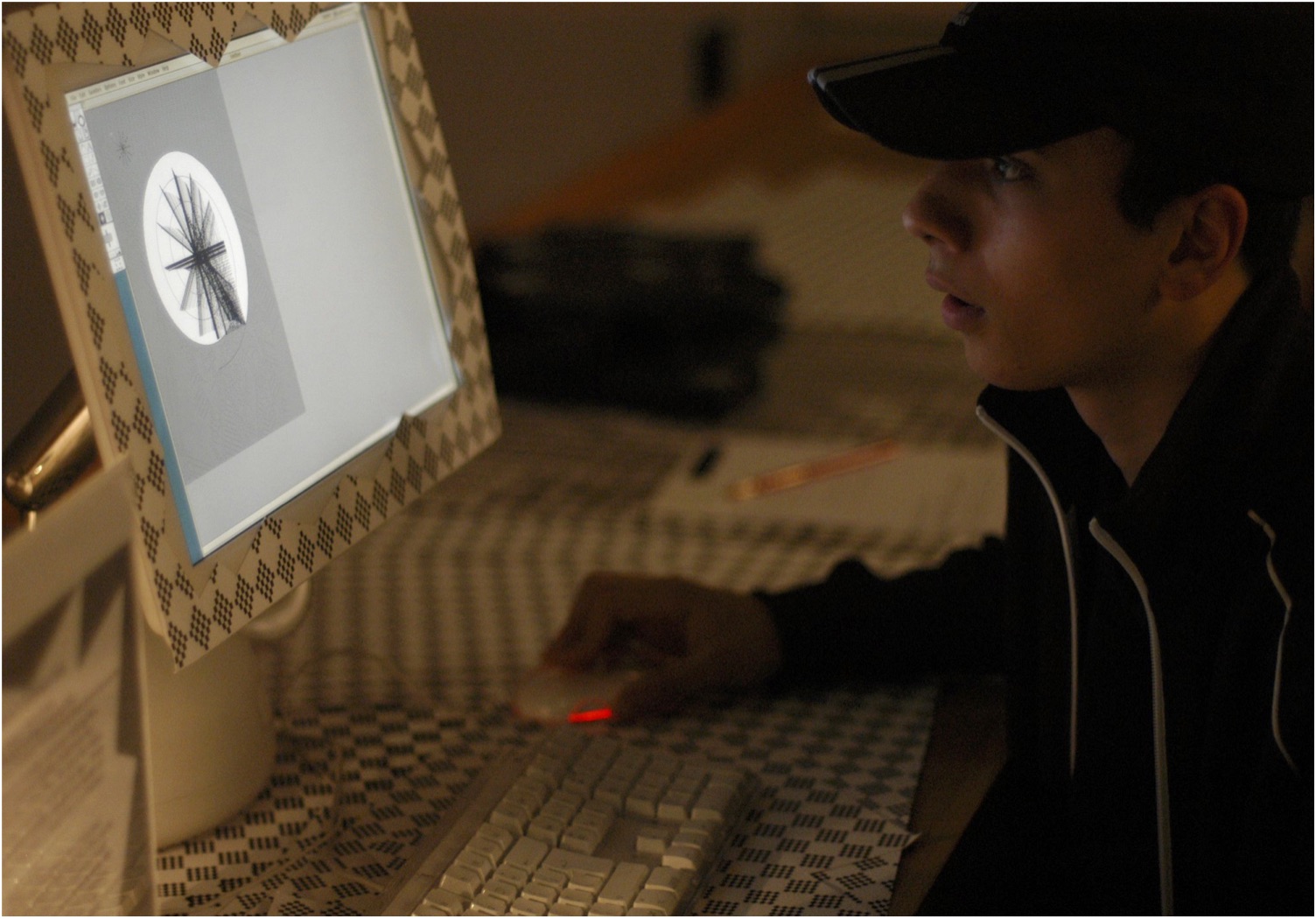

Cory’s project in Liverpool included a residency with FACT, a media arts center where I worked as a curator. He’d been invited under the auspices of the collaboration program, which paired contemporary artists with local community groups to create new works. His plan was to create infinite fill patterns and animations with a group of young people, members of a youth group called Interchill, and to set up an open-access green screen video studio.

The infinite fill pattern turned out to be a perfect basis for this collaboration, and not only because of their extreme simplicity. The results, with their black-and-white, low-tech aesthetic, seemed to strike some nerve for the Liverpool youth of 2004. They set up a green screen studio in the space, covered it in infinite fill patterns, designed infinite fill animations for the chromakey, made infinite fill clothes, and recorded carefully choreographed dance numbers to DJ Casper and Jamelia.

When the exhibition opened, members of the public could use the space to create their own videos, taking the VHS tapes home with them. I walked into the center one evening to find music playing at high volume while a group of kids rapped in front of infinite fill quasars. Grime, with its pared-down beats and its raw, blown-out sound, had emerged from the pirate radio stations in London and take its place in the hardcore continuum of UK music. The 16-bit infinite fill patterns were almost a visual analog for the alternating patterns of eight-bar rhythms used in many grime tracks, not to mention their protean, low-tech sound.

The affinity is more than coincidence. In making use of template-driven digital production, Cory follows in the footsteps of Kraftwerk by way of techno pioneer Jeff Mills, a trajectory charted by writer and artist Kodwo Eshun in his 1999 book More Brilliant Than the Sun:

As Kraftwerk realized, sound machinery de-skills and dephysicalizes music, allowing “thinking and hearing” precedence over “gymnastics.” Practicing is no longer necessary. The musician becomes an electronic programmer, a push-button percussionist who taps ENTER with the fingertips.

Embracing the tools of automation at the expense of traditional authorship, Cory is the push-button percussionist of the art world. But throughout his embrace of the digital, he differs with Kraftwerk by placing emphasis on materiality. In the case of the infinite fill zone, he placed focus on the form and function of infinite fill patterns in the digital realm, while also remediating them into a series of new analog substrates, from textile to VHS.

Per Eshun, it was Jeff Mills who famously played with the materiality of techno music and its substrates.

Pulsating lock grooves, pauses between tracks, reverse grooves, wider than normal grooves: Mills uses a series of remastering operations to alter the direction of revolution: neither forward nor reverse but cyclic.

Working within templates, but making subtle interventions into their materiality, Arcangel mines a similarly cyclic and materialist artistic vein. However, the gesture of inhabiting the machine meant something different for Mills than it does for Arcangel. Mills is a black artist from Detroit who rose to prominence in a city where workers, many of them black, could once earn a salary on the assembly line, buy a house, and organize. By the 1980s, this was no longer the case. Mills brought a radical black politics to his techno music, particularly as part of Underground Resistance (UR), which argued for a possibility of self-reinvention through technology, through techno.

Instead of retreating from machinic mutation back into an ethics of sound, UR is mutation-positive. The sampler is a mandate to recombinate—so it’s useless lamenting appropriation. Resisting replication is like doing without oxygen. the sampler doesn’t care who you are.

The sampler may not care who you are, but Eshun argues elsewhere in More Brilliant than the Sun that white culture can never achieve the alien, mutant status embraced by UR. And of course the gesture of inhabiting the machine, of embodying the principles of automation and mutation and replication, could never mean the same thing for Cory, a white Buffalonian, that it meant for Mills. Likewise, the use of lo-fi technology to create deceptively simple patterns that repeat ad infinitum could never mean the same thing for Arcangel that it meant for Youngstar.

For Eshun, white culture’s embrace of automation tends not toward mutation but toward fascination. But Arcangel finds another way. His use of automation focuses so heavily on the mundane that it can feel like a cynical take on the changing role of the artist in digital culture, a joke about the fruitlessness of cultural production in the digital age. He programs his home computer, but doesn’t bring himself into the future. Instead, he programs himself into a loop.

Welcome to the Infinite Fill Zone began from a mundane position, but it opened up into a riot of sound and pattern–thanks to the work of the participants in Arcangel’s workshop. Data Diaries, which used infinite fill patterns as a visual motif, is more typical of the truly rote, repetitive nature of much of Arcangel’s work. In this case, he followed the same process each day, translating the contents of his hard drive (a data-trash mixture of human-readable and machine-readable information) into abstract imagery.

It is clear from Arcangel’s work that he loves this repetition; the infinite fill patterns that decorate the Data Diaries website express this love. This love for the rote and the repetitive is what keeps him from falling into white culture’s usual trap of mere fascination with technology’s newness.

For evidence, look beyond the infinite fill zone to what is perhaps the most Cory of all Cory projects, AUDMCRS. The project was a meticulous online catalog of a record collection sourced from underground dance DJ Joshua Ryan. In an interview accompanying the project’s launch as part of the First Look online exhibition series at New Museum in 2013, Lauren Cornell asked Arcangel why he wanted to devote himself to such an “obsessive, time-consuming project.” His response:

I guess I wanted to treat these records with the utmost respect. You knew me in the ’90s so you know I went through a pretty hard techno/trance phase. This culture means a lot to me and I wanted to portray that. Treating them this way also plays with the discrepancy between the current cultural worth of these records (zero) and the true long-term value of them (unlimited).

For Cory, the loop is an undervalued cultural form; the fact that dance music production is template-driven, near-automated, should not detract from its cultural value.

The question of value is central. Several times throughout More Brilliant than the Sun, Eshun quotes Human Use of Human Beings by cybernetics pioneer Norbert Wiener, a text that foresaw a devaluation of human labor, and therefore human life, in the computer age. Writing in the years after World War II, as the American workforce was retrained to produce cars and television sets, Weiner noted that “the automatic machine is the precise economic equivalent of slave labor.” For Eshun, this helps explain both Black music’s embrace of the machine, and the critical establishment’s failure to take machine-made music seriously.

This is why, in Arcangel’s work, it is particularly important to understand the embrace of the repetitive, the machine-made, the seemingly mundane, as a political position driven by affection and care. For the teenagers in Liverpool who worked with him, this was implicitly obvious. They didn’t have access to the world of contemporary art, but they had a certain knowledge that came from their place of birth, a defiantly working-class port city that had been a point on the triangle of the transatlantic slave trade, and later became a battleground in the struggle for labor rights and human dignity under Thatcher. They saw the potential in turning a limited palette into a riot of pattern and volume, and they did so with gusto.