This article accompanies the presentation of A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century as part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

The history of computing can be read in manifestos. Outsized ambition and sudden breaks with the status quo have been enabled by computing’s many revolutions: freedom from longhand mental labor, from the mainframe, from the phone line, from the mainstream media, from the linear.

The ur-file is Ted Nelson’s 1974 Computer Lib/Dream Machines, a starry-eyed hypertext chapbook, which established the baseline politics of computer revolutionaries: corporate mainframe bad, personal computer good.

In his preface to Computer Lib, Stewart Brand articulates the bad using a female metaphor. “Big Nurse,” he calls it, after Ken Kesey’s Nurse Ratchet.1 Implying that while the mainframe infantilizes us as it abuses us, the personal computer sets us free. The theme continues ten years later, in The Conscience of a Hacker, the next-most seminal of the early computer manifestos. This one pits hacker against teacher:

I’ve listened to teachers explain for the fifteenth time how to reduce a fraction. I understand it. “No, Ms. Smith, I didn’t show my work. I did it in my head…”

Damn kid. Probably copied it. They’re all alike.

I made a discovery today. I found a computer.2

Nurse Ratchet, Ms. Smith: these dowagers of female bossiness are the authorities against which the hackers and techno-utopians of early internet culture rebel. What a weird reading, in a patriarchy. In a technology ecosystem so infrastructurally male, the Man is a man. VNS Matrix’s The Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century couldn’t have come fast enough.

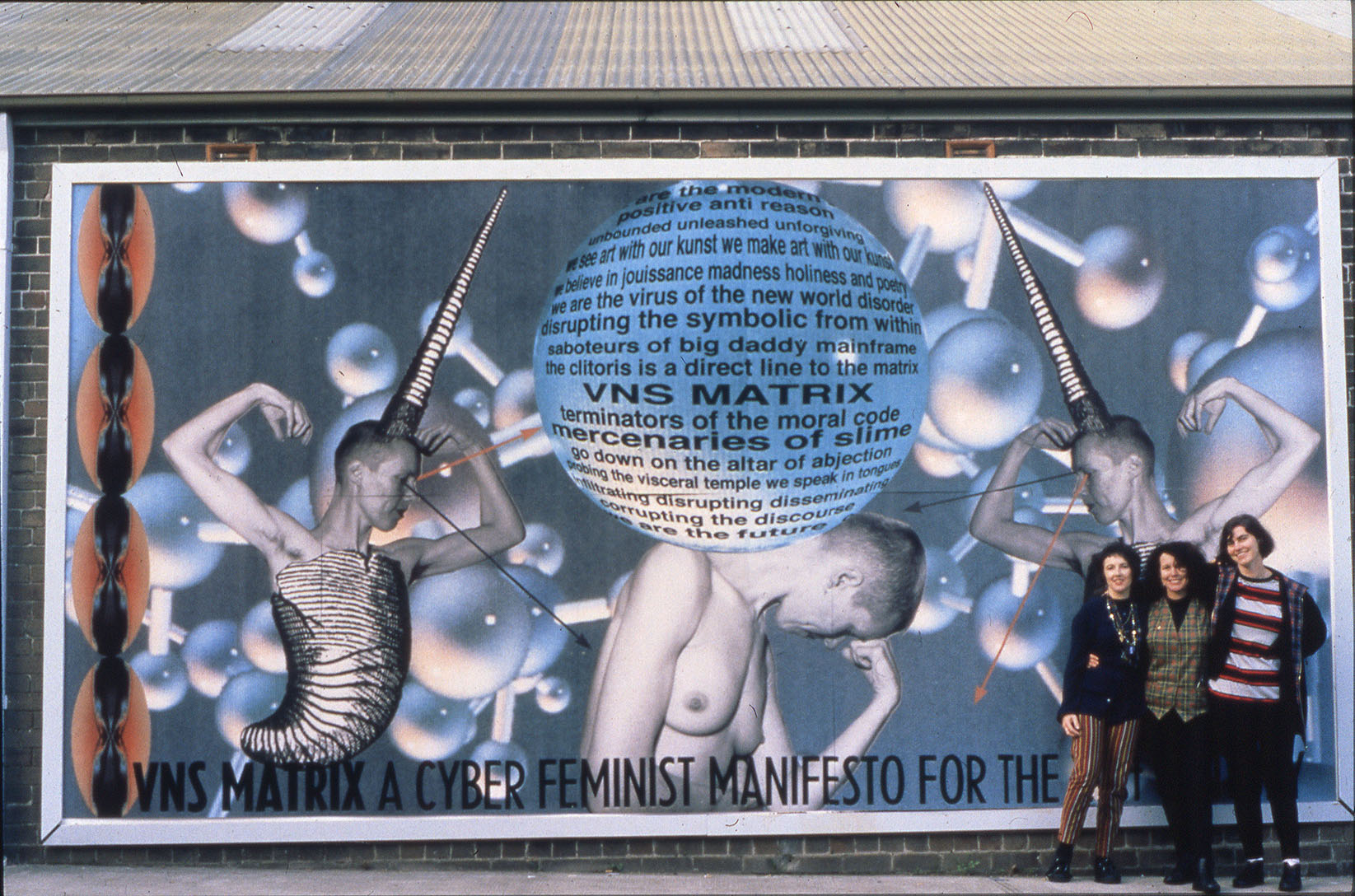

VNS Matrix was four women from Australia: Josephine Starrs, Julianne Pierce, Francesca da Rimini, and Virginia Barratt. The semiofficial genesis story is that "VNS Matrix emerged from the cyberswamp during a southern Australian summer circa 1991, on a mission to hijack the toys from technocowboys and remap cyberculture with a feminist bent.”3 Their work, which spans video, installation, game design, and texts, contains a lot of these portmanteau words—cyberswamp, technospace—and a suite of recurring characters, like a world.

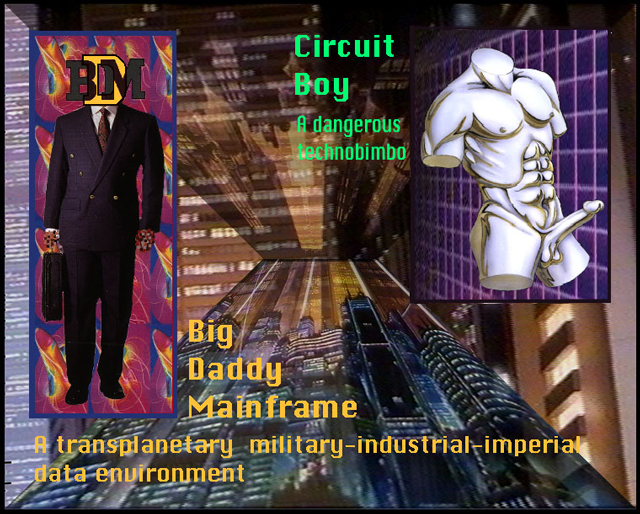

There is no Big Nurse in the VNS Matrix manifesto, and no Ms. Smith. In A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, us is a “modern cunt,” and them has a name: Big Daddy Mainframe. He is an Oedipal embodiment of the techno-industrial complex; cybersluts must slime his databanks to end the rule of phallic power. It is as much an exercise in worldbuilding as a manifesto. Later, in their computer game All New Gen , VNS Matrix would flesh out this world, depicting Big Daddy Mainframe as a Wall Street suit with a corporate logo where his head should be—a cyberpunk Magritte. His henchmen are “Circuit Boy, Streetfighter, and other total dicks.”

Still from All New Gen

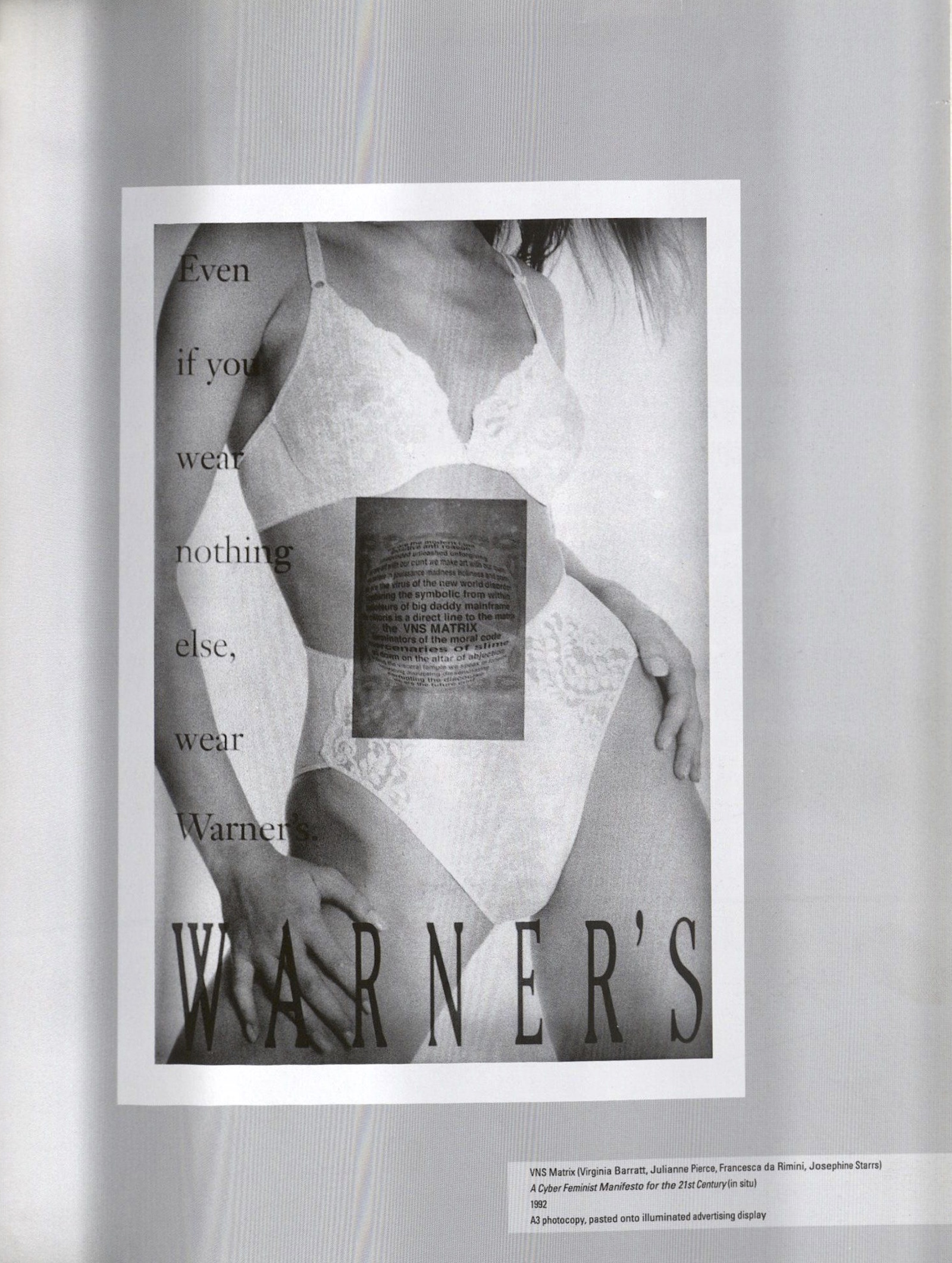

VNS Matrix wrote their manifesto in 1991, two years before there was a decent browser with which to surf the web. It began as a printed A4 size flyer, with the short text mapped onto a sphere bordered by a vagina motif. “We went around the city and pasted it up, you know, with the flour paste,” da Rimini remembers. “Then we actually had to repaste over them a couple of days later, because we had a spelling mistake.”4

VNS Matrix, A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century (1991). Photograph of A3 photocopy, wheatpasted onto advertising light box, from Art + Text no. 42, May 1992.

They sent it by fax to Kathy Acker and Sandy Stone and Wired and Mondo, and later circulated it on LambdaMOO and IRC channels. They left piles of posters at art galleries, and created a billboard version, eighteen feet long, for exhibition. The text bulged from one spherical fragment of DNA, accompanied by images of a chimera unicorn in a shell. When the billboard was mounted on the side of the Tin Sheds gallery in Sydney, a student from Britain photographed, framed, and brought it back to her professor, the cultural theorist Sadie Plant, who was working on a curriculum around the same themes. In her 1997 book Zeroes + Ones, Plant draws the link between VNS Matrix and Donna Haraway and explains that when they write “the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix,” they mean both the womb—matrix is Latin—and “the abstract networks of communication…increasingly assembling themselves.”5

Sadie Plant and VNS Matrix are considered co-authors of the word “cyberfeminism.” Science fiction people call this Steam Engine Time: that moment in history when a technology, or an idea, is so bound to happen that it’s invented by several people at once. Like the steam engine, cyberfeminism was inevitable. Many of its early champions were feminist artists moving online, people like Faith Wilding and Lynn Hershman Leeson. In the late 1970s, consciousness-raising happened in living rooms, with groups of women sharing experiences, but it had global ambitions. The internet collapsed the difference, creating the global living room, where nurses and teachers could be hackers too.

Cyberfeminism took up the techno-utopian tone of of early internet culture and turned it on its head. It was a tone inherited from Ted Nelson, Stewart Brand, and the West Coast cyberhippies who believed computer-mediated communication would create a “civilization of the mind,” as another computer manifesto, John Perry Barlow’s 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” described it.6 But for VNS Matrix, cyberspace was never free of the body. “Lots of computer technophiles,” Starrs said in 1992, “jack into the machine and want to forget about the body, to reject the meat of the body. In our work we’re not finished with the body, the body is an important site for feminists.”7 Not a civilization of the mind—a world of slime.

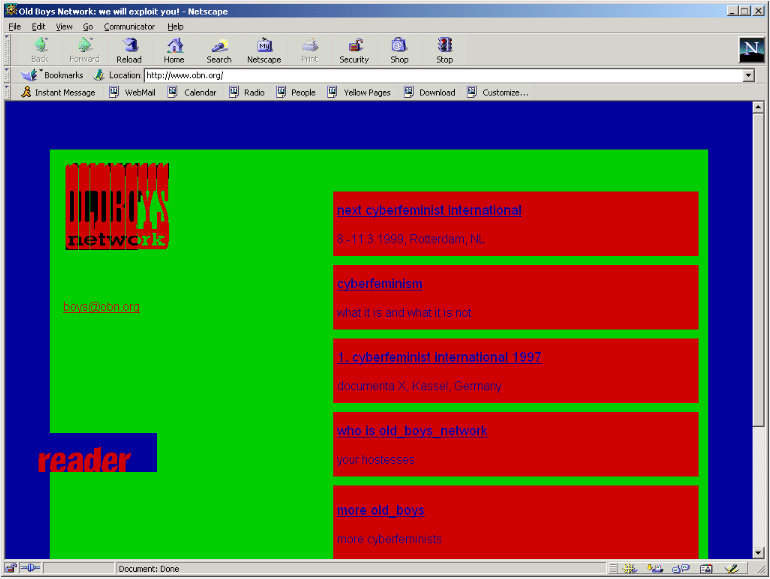

The world sketched out in the manifesto was soon clamoring with voices. In 1997, a group organized by the Old Boys’ Network assembled in Kassel for the First Cyberfeminist International, piggybacking on Documenta X, to clarify and discuss the intent of the movement. It seems they couldn’t agree; they wrote cyberfeminism’s second manifesto, The 100 Anti-Theses of Cyberfeminism. It listed everything cyberfeminism was not. This included not a media-hoax, not postmodern, keine praxis, and “not about boring toys for boring boys.”8

Screenshot of Old Boys' Network website, crawled by Internet Archive in 1999. Via Oldweb.today.

Cyberfeminism was nothing if not many different, often contradictory, movements at once. “Cyberfeminism only exists in the plural,” pronounced the Swiss art critic Yvonne Volkart at the second International two years later.9 It could never be trusted to mean any single, specific approach to feminism at the dawn of the internet. The internet tends to refute specificity, favoring instead the multiple, making cyberfeminism—in all its slipperiness—if nothing else, representative of the medium.

And such slipperiness is human, which VNS Matrix’s The Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century establishes clearly. This might be the manifesto’s most lasting note. It is a bodily text: in seventeen lines, it covers cunts, the clitoris, tongues, slimes, orgasm, and a virus. Doing so, it articulates feminism on the internet as visceral—related to viscera, slime, wetware, and birth. It still feels that way: messy, howling, but very much alive.

-

1. Nick Montfort and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, The New Media Reader (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 301.

2. Manifestos for The Internet Age (greyscale press, 2015), 32.

3. http://motherboard.vice.com/read/an-oral-history-of-the-first-cyberfeminists-vns-matrix

4. Interview via Skype with Francesca da Rimini conducted by Aria Dean and Michael Connor, October 24, 2016.

5. Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones: Digital Women + The New Technoculture (London: Fourth Estate, 1997), 59.

6. Manifestos for The Internet Age (greyscale press, 2015), 39.

7. Interview with VNS Matrix by Bernadette Flynn, 1992.