The Download is a series of Rhizome commissions that considers posted files, the act of downloading, and the user’s desktop as the space of exhibition. Elisa Giardina Papa's Technologies of Care, the latest in the series, is now on the front page.

“What are you up to?” asks Worker 7: bot? virtual boyfriend in a computer-generated voice. She replies that she’s busy. As the conversation unfolds, the artist and the online worker, who may or may not be a bot, struggle to understand and connect with each other.

Empathy, digital labor, and new ways to serve and care on the network are the subjects explored in Elisa Giardina Papa’s Technologies of Care, commissioned by Rhizome for the Download. Giardina Papa presents portraits of online workers in a 26MB ZIP file; six are identified as women, plus the possible bot. Each portrait is its own folder, activated by an HTML file marked “play_it.” Seven browser-based conversations are included in the Rhizome download, but Giardina Papa has produced a total of 25 for installation in “Cyphoria,” a section of the 16th Art Quadrennial in Rome curated by Domenico Quaranta.

In one of the dialogues, Giardina Papa describes to Worker 7 that her interest is in women who perform new types of network-based affective labor: “forms of work that are intended to produce emotional experiences in people.” As presented in Technologies of Care, the conversations sketch out distinct positions: the artist plays the role of the researcher, inquiring into the nature of this outsourced work; the workers reply. The sessions took place via Skype, chat, text messaging, and shared text docs, and traces of these platforms are evident throughout.

Giardina Papa hired the workers she interviews. In other words, the artist here is also a client, collaborating in the construction of her own work. “If you have more questions about me, you can ask, ok?!” (Worker 4.) At times, we’re keenly aware that the interview we’re listening to is itself a paid transaction: work negotiated with the artist, who will use the exchange as raw material. These workers are working. Using freelancer platforms like Fiverr and Upwork, the artist reached out to skilled employees and negotiated their conditions. Unlike marketplaces like Mechanical Turk, these platforms allow for direct contact with the service provider, which Giardina Papa used in order to explain her research in advance and confirm rates with the workers.

With Worker 7, the transaction teeters. The bot’s nagging demands (“I miss you!” “what are you up to? “are you mad at me?”) and Elisa’s replies (“I am at work now. actually I have to run into class, can I text you later?”) ask us to consider the emotional space of the artist as a digital worker herself, and the artist’s labor enters the scene explicitly. Evidence of these negotiations in Technologies of Care is scant, but they manage to cast authorship and control into precarious light. The exchange with Worker 7 is the only interview where Giardina Papa is asked questions in return. “I don’t understand, you think I’m getting paid to chat you up?” he/it asks. The bot reverses the game.

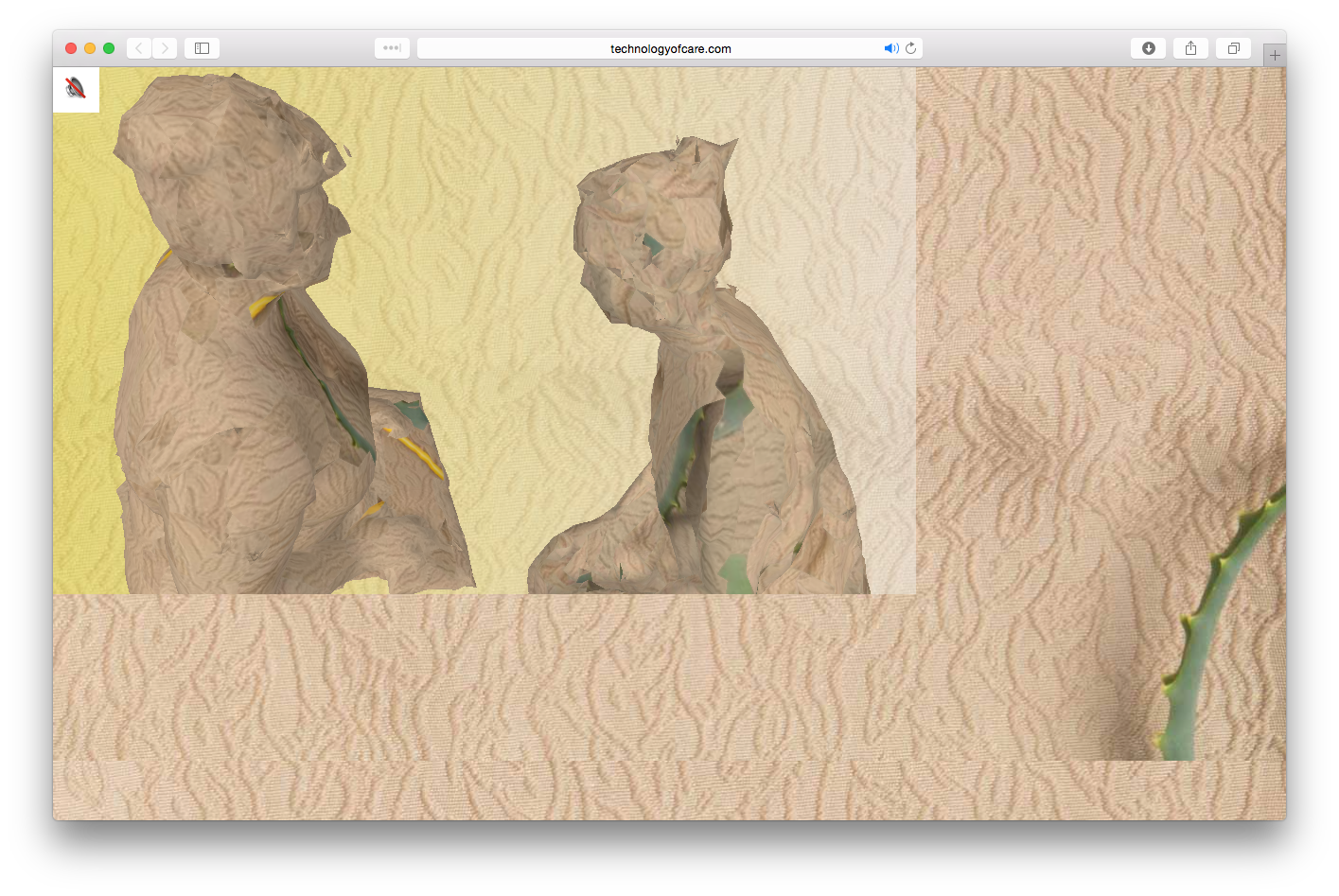

For each episode, a script takes over the user’s browser with flowing sound, text, and images, informed by details from the interviews. It’s a downloaded work, but Technologies of Care is not entirely local—digital 3D models of scanned shapes and silhouettes based on textures borrowed from the workers’ domestic environments, hosted on remote servers, are served up and animated on the spot. It's a real-time performance, an on- and offline collaboration in the browser. Outsourced work and service of another kind.

Giardina Papa visualizes—and gives voice to—invisible caregivers on the network: laborers who provide microservices, fetish work, and emotional support. We are introduced to an ASMR artist, an online dating coach, a fairytale author and video performer, a social media fan, a researcher and nail wraps designer, and a customer service operator. She finds these freelancers in Brazil, Greece, the Philippines, Venezuela, and the US, working anonymously through third-party companies that profit from these connections. Except for the virtual boyfriend, all of the interviews are performed as flat, female-sounding voices. Sometimes the interviewer and the interviewee are rendered as the same English-speaking voice. The need to modulate presentation through gender, voice, or language on the network is central here: how work is negotiated, how stories are managed. Worker 1 reveals that she and her daughter work together under a single “male” account on Fiverr—it’s an example of the way identity is performed under precarity.

The sessions read like ethnographic research but onscreen they play out like vibrant paintings. Within Technologies of Care’s even pace, distinct individuals and stories surface; details like Worker 1’s “slave-like” jobs and customers that “need to be nurtured” (Worker 3) suggest that these women are engaging with new modes of working, caring, and production that are complicated, at best. The domestic textures visualized by Giardina Papa are familiar; they humanize the anonymous caregivers, but maybe also echo the downloader’s own physical environment. Technologies of Care asks us to pay attention to these relationships, to the spaces between voices—to consider how close watching and listening to others on the network might link us together from all sides of the screen.

Click to download work:

The Rhizome Commissions Program is supported by Jerome Foundation, GIPHY, American Chai Trust, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.