The Download is a series of Rhizome commissions that considers posted files, the act of downloading, and the user’s desktop as the space of exhibition.

Zac’s Freight Elevator by Dennis Cooper is part of The Download, and the zip file is available here.

On Thursday, November 16, there will be a night of interpretative readings of Dennis Cooper’s GIF novels at New Museum. More information and tickets available here.

On June 27, 2016, Google deactivated the popular blog of writer and artist Dennis Cooper. Visitors to the site were shown this message:

Did you expect to see your blog here? See: ‘I can’t find my blog on the Web, where is it?’”

Fourteen years of artistic output archived on the Google-owned Blogger site appeared to be gone, along with Cooper’s latest work, Zac’s Freight Elevator, a novel composed of hundreds of found GIFs. The epic work-in-progress was stored on private pages on the site.

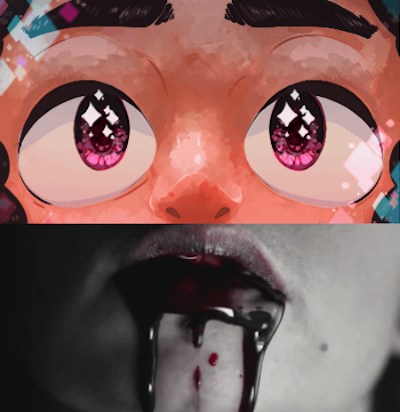

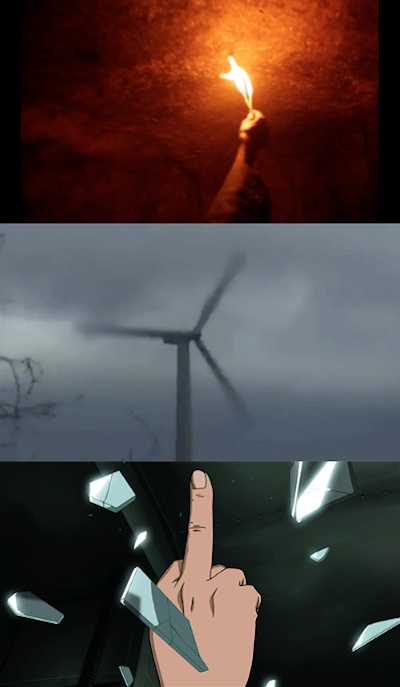

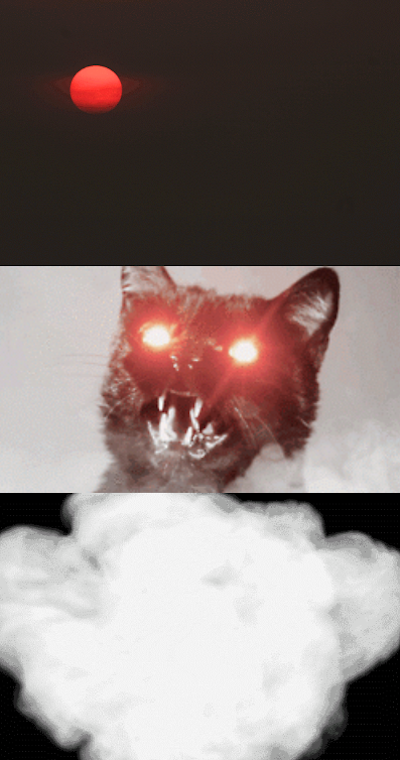

At the time, Cooper had already published two other GIF works: a novel (Zac’s Haunted House, 2015) and a collection of stories and poetry (Zac’s Control Panel, 2015). These took the form of simple browser-based websites, experienced offline (available as ZIP downloads at Kiddiepunk). To create his image-based narratives, Cooper arranges the found GIFs into vertical sequences, two or three at a time, and then stacks them into tall columns, which are scrolled. Earlier versions of the GIF works originally appeared as long blog posts.

Cooper has a deep history with experimental publishing, having started the zine Little Caesar (“a literary journal with an anarchist, punk rock spirit”) in 1978, and he continues to maintain his own small press, Little House on the Bowery. He was an early blogger, and the online space that he nurtured functioned like a public extension of his artistic practice. Deep mixes of images, videos, music, excerpts from books, notes, and sampled correspondence were featured daily, sometimes around specific themes like male escorts, horror films, weird phenomena, film directors, or composers.

Google offered no explanation when it deactivated the site, and Cooper struggled to get information from the company for two months. He used Facebook to update friends and fans, posting links to the spectacular international coverage the situation was garnering (with headlines like “Dennis Cooper: Deleted by Google” and “The Blog that Disappeared”). And after an intense period of legal discussions and negotiations, Google finally explained that the act stemmed from a single complaint. An image, posted ten years prior, had been mistakenly identified as child pornography. On August 26 Cooper announced on Facebook that Google had returned his data and that he was relaunching his blog, which he now maintains on Wordpress.

Lost for two months but now complete, Zac’s Freight Elevator is presented here as a Rhizome Download (in collaboration with Kiddiepunk).

The urgency of the work as a rescued object is in sharp contrast with the immutability of its form. Organized into six chapters, each of the 608 found GIFs in the novel has a history of distributed authorship, continuing to exist simultaneously in any number of contexts, having been copied, stored, and served up on the web countless times. Each GIF contains its own trajectory; with a bit of sleuthing, other histories are glimpsed. An animation of a walking man that appears early on in Chapter 1 seems to have been featured on the site Lyst.org in 2004–05, but remains accessible in an archive. Further down the page in Chapter 1, a black-and-white anime-style animated GIF that could easily be seen as a quick one- or two-image sequence turns out to be, upon close examination, an elaborate 150-second animation. It’s a Gravity Falls fan fiction, an intense scene between the twins Mabel and Dipper Pines, originally posted on DeviantArt. By pairing it with a mysterious swarm of black dots moving in and out of focus, Cooper suggests something nameless, shapeless, and haunting. One pictures Cooper browsing, searching, and curating the GIFs from all corners of the web in the sculpting of Zac’s Freight Elevator. Assembled and neatly stacked into sequences, these re-authored GIFs are perfect examples of “poor media”—compressed forms that privilege accessibility, remixability, and circulation over quality. GIFs are meant to be shared. GIFs persist. And for artists who extend their practice to online platforms, dispersion of files may be more than making public — perhaps it’s also a kind of preservation.

At a recent film screening in NYC, Cooper said that he sees GIFs as language, as individual words or paragraphs. “I create fiction without writing,” he explained, though by stringing together hundreds of GIFs he performs another kind of writing. The sequences are uncanny; meaning accumulates in the browser window as the reader scrolls through stacked GIFs, shifting from clip to clip. Out-of-sync oscillations seem to sound out, giving the work a somewhat aural quality. Individual characters and plot lines are less resolute and appear more like semiotic gestures: the young boy, the older man, the screaming mouth, the suicidal blow. Pictured are bodies that flow in and out of sexuality and violence, play-acting roles. Imaginary scenes are sketched out for consideration.

Experienced as stacks of meaning, Zac’s Freight Elevator is a masterful work of montage. In early cinema, images piled up on top of each other to create accumulating layers of meaning, reverberating in the deep space between the viewer and the screen. Cooper’s GIF novels echo this pile-up, but in a vertical way—they resemble endlessly scrolling Tumblr pages (as well as his own blog), inviting us to decode the relationships between signs streaming by, a relentless production machine of emotion. Cooper’s GIF novels may look like Tumblr, but they recall older form of reading, like the emakimono (“paper scrolls”) of medieval Japan: long-form, continuous image-based sequences that are carefully controlled by the reader. Cooper “folds up” the narrative into chapters, reminding us that early scrolls were eventually folded up to form “pages,” and then bound (the codex).

Cooper preserves his GIF novels by spreading them. Files that replicate on the internet are safeguarded; copies persist, traceable both on and off the network. Given Cooper’s recent problems with Google, let’s see Zac’s Freight Elevator as a work of visual literature that sustains itself by staying in motion. Maybe it’s a radical notion, an act of resistance against the corporate Terms of Service paradigm that threatens entire archives with a single glance. The animated GIF reminds us, perhaps naively, that internet culture can be material for a deep archeology of shared authorship and meaning. Publishing a GIF novel in the form of a freely downloadable ZIP file preserves the work, protects the artist, and extends the generosity. The Rhizome Commissions Program is supported by Jerome Foundation, GIPHY, American Chai Trust, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

The Rhizome Commissions Program is supported by Jerome Foundation, GIPHY, American Chai Trust, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.