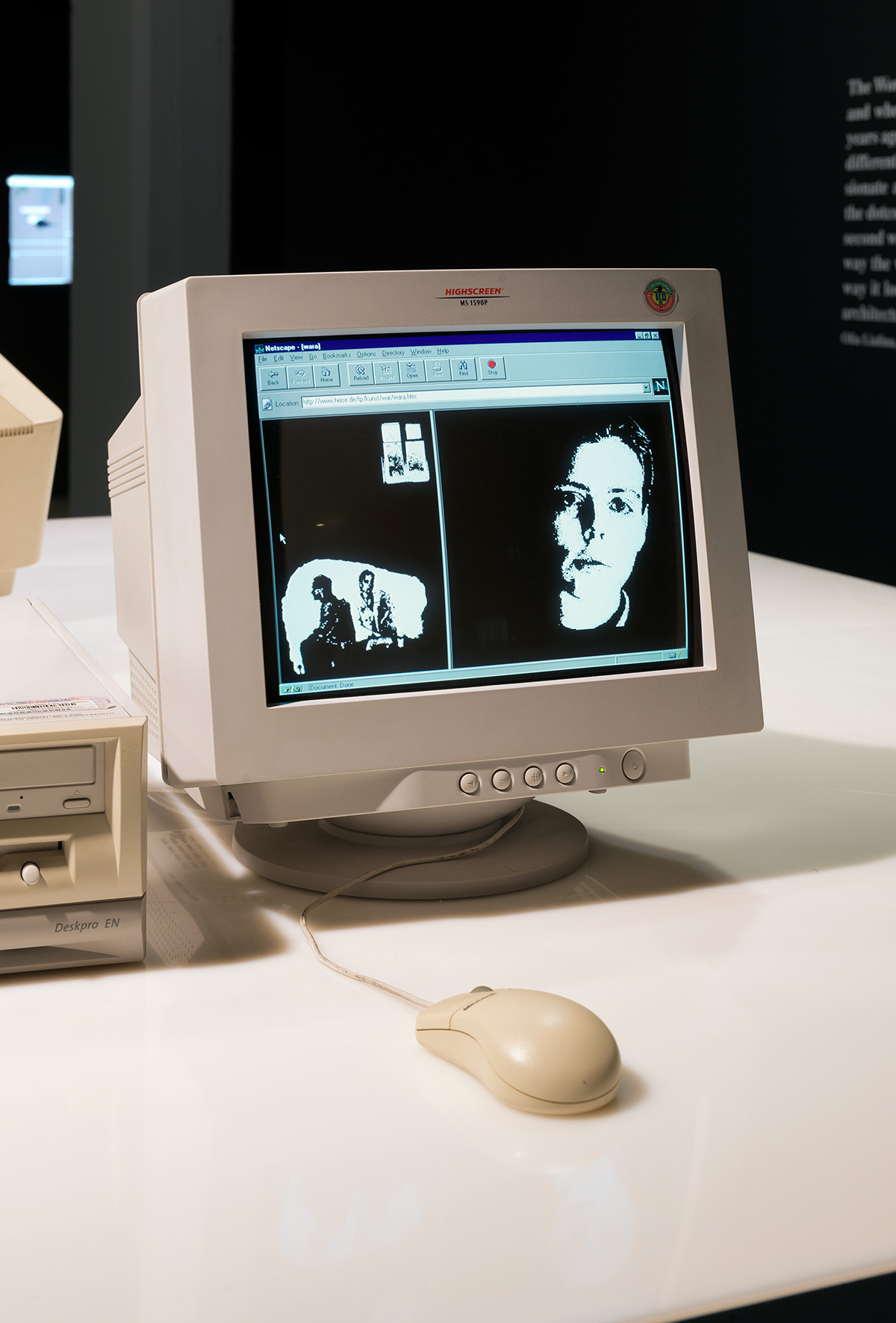

This article accompanies the presentation of Olia Lialina's My Boyfriend Came Back from the War as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

An earlier version of this article was published in MBCBFTW: online since 1996, and appears here with permission from H3K.

“If something is in the net, it should speak in net.language,” net artist Olia Lialina told critic Josephine Bosma during an interview at Ljudmila Media Lab in Ljubljana in May 1997.1 Eight months earlier, Lialina had created and published her first work of net art, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (MBCBFTW). Through hypertext, black-and-white bitmap images and the frames of a web browser, the work tells the story of an awkward reunion between a young woman and her boyfriend. They sit together without making eye contact and their conversation is at cross-purposes: an affair is alluded to; the trauma of war looms over the encounter; a marriage proposal is made and deferred.

With its use of browser frames, hypertext and images (both animated and still) to share a personal story, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War quickly earned critical attention and today is one of the most widely cited examples of the artistic use of HTML on the early web. Despite the novelty of its approach and the euphoria surrounding its then-futuristic medium, it evokes a somber, melancholic mood. The medium of the web promised connection, but the story the work tells is one of estrangement, of the impossibility of relationships under conditions of geopolitical conflict. Nevertheless, the melancholic tone of My Boyfriend Came Back from the War reflects a core function of net.language, as articulated in Lialina's body of work as a whole: the elaboration of memory.

Web Language

Bosma’s interview with Lialina took place against the backdrop of a conference, organized by the nettime mailing list, that convened a network of artists, thinkers and activists who shared an interest in the creative and political possibilities of the internet. They had escaped to a back room while “an American history lesson of the internet” went on in the front; the headlined topics included “What is net-art?” and “on/offline publishing,” “media activism,” and “The Beast – the East.” Some discussions focused on the role of the Soros Foundation in the region – “our dear Uncle from America,” as participants facetiously called its founder, in an attempt to “discuss his almost obscene power position in Eastern Europe.” 2

It was a time in which the web “was a novel and astonishing thing and its very existence seemed problematical,” to borrow from Christian Metz’s description of early cinema. 3 Everything needed to be theorized and the nettime conference was an important context for this.

During their conversation, Lialina told Bosma that her approach to My Boyfriend Came Back from the War reflected her interest in applying a cinematic language to the net. After making it, though, she became more interested in “net.language itself” and questioned whether it was specific enough to the context of the net. “This story can exist on cd-rom or you can make a video out of it,” she told Bosma. 4

The dot between net and language, presumably inserted by Bosma during transcription, mirrored the punctuation of “net.art,” the term coined by Pit Schultz for a 1995 exhibition and later popularized by Slovenian artist Vuk Cosic to describe artists who embraced the web as medium and context. In particular, the term has been associated with Cosic’s May 1996 conference “Net.Art Per Se,” an important meeting of artists associated with the early web. (Lialina was not involved; her first work of net art appeared several months later.) Net.art at that time often took the form of web pages or websites, but it also involved other internet-based applications such as email, as well as more tangible materials and practices such as chalk graffiti or live performance. (Cosic even told Bosma that the nettime conference itself, as a convening of a network, could be considered net.art.) 5 Thus, the term should be understood in a very broad sense. However, Lialina’s discussion of it with Bosma focuses in particular on the context of the web and My Boyfriend Came Back from the War was created specifically to be experienced in a web browser (given, for example, the use of frames.) Thus, the language at stake in her work can be understood as the language of the web specifically.

Lialina’s focus on language makes it hard not to think of the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who wrote (in 1934) of cinema’s emergence from theater:

In the early 1920s we all came to the Soviet cinema as something not yet existent. We came upon no ready-built city; there were no squares, no streets laid out; not even little crooked lanes and blind alleys, such as we may find in the cinemetropolis of our day. We came like bedouins or goldseekers to a place with unimaginably great possibilities, only a small section of which has even now been developed.6

What was at stake for Eisenstein in creating this new language begins to become clear later in the essay, when he describes film-language of the revolutionary period “as an expression of cinema thinking, when the cinema was called upon to embody the philosophy and ideology of the victorious proletariat.” “Film-language” was needed in order to express broader societal ideas that perhaps could not have been fully expressed by other means.

To understand what societal ideas are at stake in the net.language advanced by Lialina, it is necessary to begin with a consideration of formal aspects of her first artwork for the web.

SPATIAL MONTAGE

“My boyfriend came back from the war. After dinner they left us alone.”

Underlined white text appears in the upper right-hand corner of a black browser window. No typeface is specified, so the text renders in the browser’s default font. The text remains white when clicked, and on return visits.

Today, few websites would leave typeface unspecified, but this practice was the standard in the very early days of the web, circa 1993. According to Lialina, this early style reflected:

the belief of the early 1990s that any visual design should be left at the discretion of the user. Page authors wouldn't define colors, fonts margins and line-lengths. In turn end users set their preferences for colors, fonts, links, graphics in their browsers, according to their needs or taste. Not a big deal, one can say, to decide if to see all the pages of the internet on a white or a gray background. But don't think about colors, think about the concept – each user was defining the look of the whole WWW for themselves. 7

The browser was also an editor and users were given latitude to display web pages in the way they preferred. This was a marked departure from print-based publishing, in which the typeface was determined at the time of publication, not reading, but it was common practice only for a short time. Lialina goes on to describe the transition, over the next several years, to a vernacular web in which the creators of pages began to play with decorative formatting, often by changing the color of text. By the time of My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, this more decorative approach to text styling would have been the norm.

The text in My Boyfriend Came Back from the War still allows plenty of latitude for style to be dictated by the user, but defines a specific color. It also assigns the same color to the text no matter what state of usage it is in—a departure from convention. The typical approach was to change the color of linked text when clicked by the user and to display previously followed links in a different color as well. Lialina chose to restrict her typeface (in any state) to white, rather than giving this kind of responsive feedback to the user. This color is clearly of great importance—it sets up a color scheme that continues on the next page.

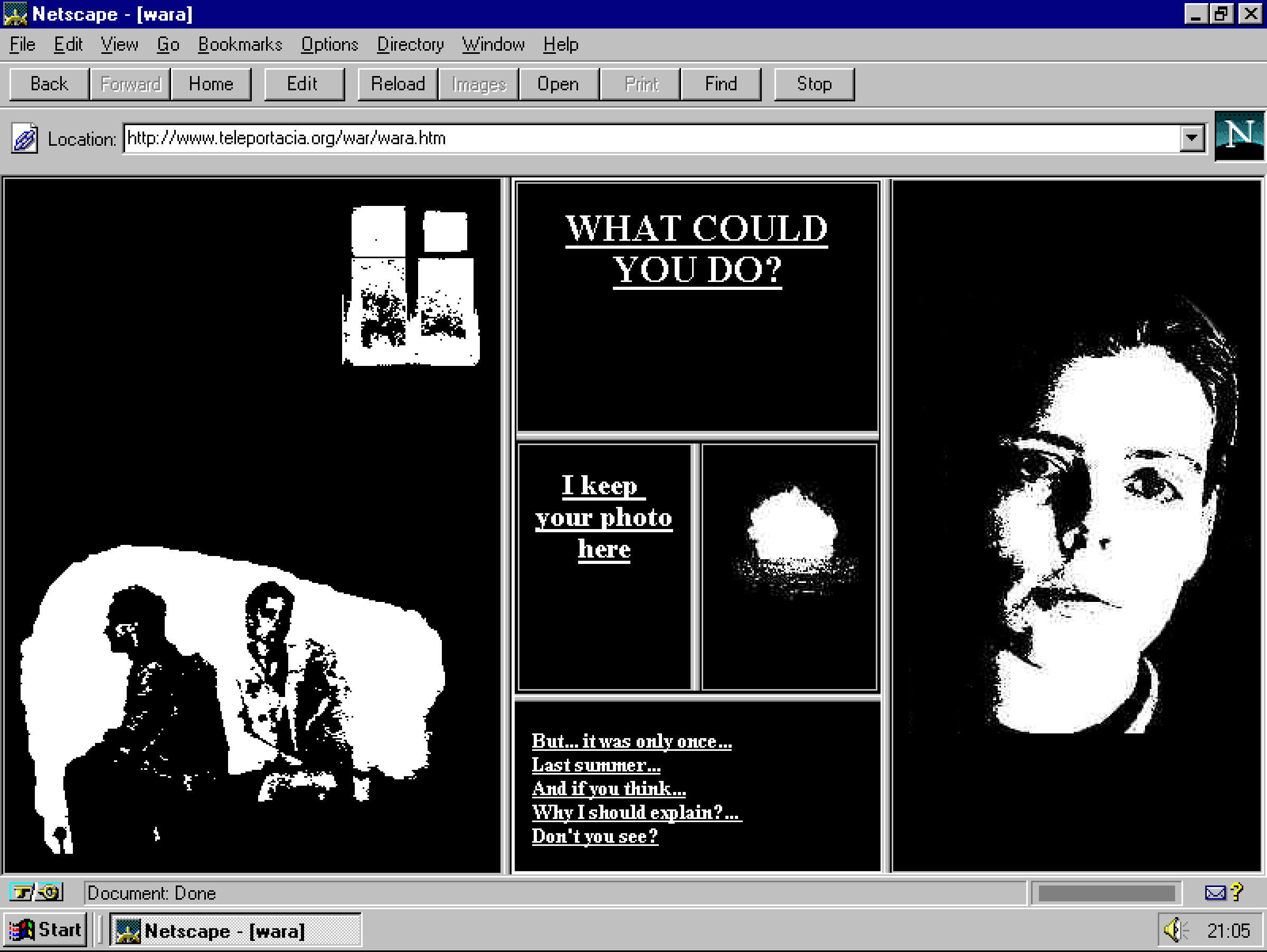

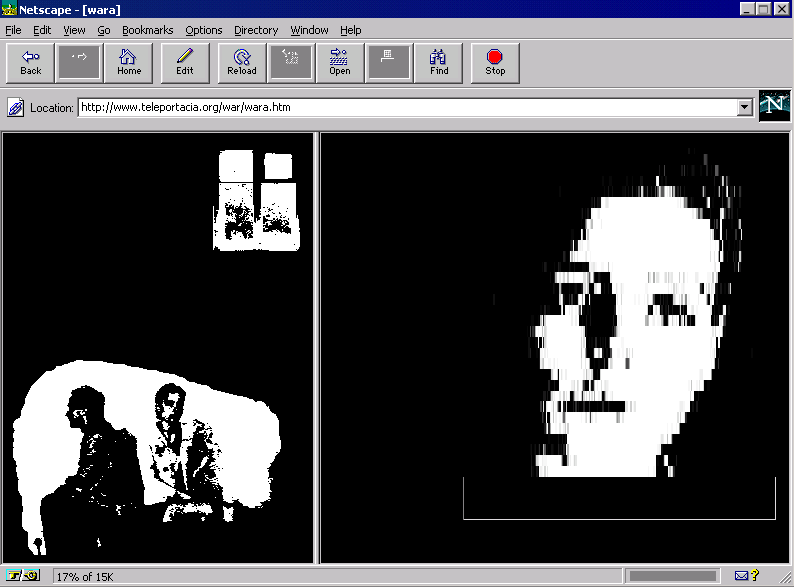

Clicking on the linked text opens a page with bitmapped black-and-white images. On the upper right is a window looking out to some vegetation, and on the lower left a man and a woman sit awkwardly, looking away from one another. The sizes of these images are determined as a percentage of the browser window’s width, always taking up the same proportion of the screen. They are positioned with the aid of a third, invisible image that sits between them, acting as a spacer. At any scale, the seated couple is isolated within a much larger expanse of black. The window above them seems to admit no light and the foliage outside harbors secrets. It seems to be a negative image, with the whites and blacks reversed.

The stark contrast and jagged contours of the images gives them the appearance of high-contrast early film stock or newspaper photographs while keeping the file sizes very small: These are one-bit images in which each pixel can be only black or white. The binary color scheme thus reflects the underlying logic of the computer itself, while contributing to a sense of stark choices and engulfing darkness. Despite the small file sizes, these images would load somewhat slowly on a dial-up internet connection; Lialina has spoken about the importance of the pacing afforded by this characteristic of internet infrastructure in 1996—a unique material affordance of the web, mobilized in the creation of an emotional universe. 8

With the next click, a single vertical divider splits the page. The image of the man and the woman from the previous screen reappears at smaller scale in the frame on the left, where it will remain until the end of the work. Likewise, the image of the window reappears but now it has been transformed from a still to a four-frame animation, displayed as an animated GIF. The image has been reversed – white areas are now black, as if the prior image had been a camera negative for this one – and the image flickers as if being shown on an old film projector.

These very direct allusions to film stock and early cinema suggest that other possible parallels could also be drawn. The texts can be thought of as intertitles setting up narrative scenes; the images can be read cinematically as establishing shots, close-ups and so forth. These parallels bring special attention to those aspects of the work that are quite foreign to cinema. One point of departure, though, is the way in which the work adapts ideas of cinematic montage to the web.

Christian Metz placed special emphasis on the role of montage in defining early cinematic language in the landmark work Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema.

[M]ontage, through the enthusiastic and ingenious exploitation of all its combinations, through the pages and pages of panegyric in books and reviews, became practically synonymous with the cinema itself.

More direct than his fellows, Pudovkin was unwittingly close to the truth when he declared with aplomb that the notion of montage, above and beyond all the specific meanings it is sometimes given (end-to-end joining, accelerated montage, purely rhythmic principle, etc.), is in reality the sum of filmic creation: The isolated shot is not even a small fragment of cinema; it is only raw material, a photograph of the real world.9

For Pudovkin, cinema is created when one image (or intertitle) is joined to the next. In early cinema, this joining happened in space—with one frame of film attached along its edge, with splicing cement, to another—but it was experienced in time: An image appeared onscreen, followed by another. In cinema, this point where one image is sutured to the next is, perhaps incongruously, referred to as a cut, although it seems defined more by conjoinment than disjunction. In My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, separate frames are joined together by HTML code and the browser itself and experienced in both space and in time, employing what Lev Manovich has characterized as spatial and temporal montage.

The first transition in the piece resembles a cut in cinema quite directly. An intertitle appears and then is replaced by an image that fills the window; the only difference is that here, the user chooses when to make the “cut.” This is temporal montage.

Spatial montage is introduced in the second transition. The window is divided, with the initial image of the couple on the left, slightly transformed, and a close-up image of the young woman on the right. Instead of each image being replaced by the next onscreen, here the initial image remains as further frames appear alongside it.

As the user continues to explore the frame on the right-hand side, the page is divided into smaller and smaller sections in which sequences of image and text are interwoven. At no point is it necessary to scroll. This allows for images and texts to be “joined” to one another not only in time but also in the two-dimensional space of the browser window.

The strategy of subdividing the frame into smaller windows was present in cinema, too. Lev Manovich has discussed the use of this kind of “spatial montage” in cinema in his book The Language of New Media. Edward Porter’s The Life of an American Fireman (1903) used the technique to show a firefighter’s daydream above him as he sits in the firehouse; Abel Gance used the technique in his epic three-screen drama Napoleon (1927).

Lialina’s narrative use of spatial montage differs from these examples in the way it denotes the passage of time. In cinema, the split screen is often used to show two scenes progressing in lock step. When the screen splits in Lialina's work, it also divides the temporal flow of the story; the frame on the left remains the same while the one on the right continues to move forward. Different temporalities begin to coexist, all of them framed by the image of the young man and woman beneath the window, which is left unchanged. Time moves forward, but the larger scene remains unaffected, and various elements progress independently of one another.

The strategy of montage in Lialina’s work also differs materially from that in cinema. In cinema, temporal montage involves splicing distinct image sequences together at the boundary of a frame; spatial montage involves optically compositing distinct sequences within the frame. The montage in Lialina’s work is described in HTML code. While web pages are often generated with the aid of software, Lialina’s code appears to have been written by hand. For example, when the close-up image of the young woman appears, it is set to take up 70% of the width of the frame. The html code for this image includes the misspelled and therefore unused attribute “hight=’70%’”, which suggests that the HTML code was written by hand and serves as a reminder that the code is based on the English language.

MULTILINEARITY

While spatial montage in cinema takes place within a linear temporal structure, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War is what George Landow calls “multilinear.” 10 Its

…multilinearity allows contradictions in the text to be foregrounded, instead of smoothed out and eliminated as is often the case within a paradigm that carves the world up into simple oppositions of male and female, black and white. 11

This description, drawn from a text about the feminist potential of hypertext as a narrative form, illuminates a key dimension of the departure from montage in the work. Montage was notably defined in terms of a dialectic opposition reaching a synthesis, a structure that Eisenstein argued was crucial to cinema’s status as a revolutionary form.12 One image plus a second, contrasting image would result in a synthesis, a new, third meaning. In the linear montage of early Soviet cinema, binaries were set up only to be subsumed into a larger coherent whole. In the case of My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, binary oppositions fracture into a prismatic composition that allows many possible points of connection between individual frames.

The multilinearity of Lialina’s use of multiple windows reflects the specific affordances of HTML frames, introduced by Netscape in 1995 as a feature of the Navigator 2.0 browser, which supported multiple documents loading in discrete areas of any given page. Thus they allowed the user to move dynamically through certain parts of a page, updating or interacting with individual elements while other parts remained static.

Up to this point, I have described only the first two frames of My Boyfriend Came Back from the War; there are seventy-six in total. From the second frame, a click on the close-up portrait on the right-hand side divides that frame in half. Now there are three frames arranged vertically across the screen. The portrait shifts to the right, reduced in scale, while the text “Where are you? I can’t see you” appears in the middle.

When clicked, the text cuts to an intertitle that reads: “FORGET IT.” Clicking again divides the frame into an upper and a lower section. The upper displays another negative image of soldiers under a helicopter, while the lower reads “you don’t trust me. i see.” Then:

But... it was only once...

Last summer...

And if you think...

Why I should explain?... Don't you see?

The intertitles relay a dialogue between the estranged lovers, although the speaker of any given line is not identified. There are further allusions to possible infidelity, discussions about an act of violence, and a marriage proposal, deferred.

The images serve a wider range of roles. At times, they seem to reflect the boyfriend’s memory – such as the helicopter, which is replaced with a negative version of the same image when clicked. At other times, the images seem to illustrate the dialogue – for example, “I keep your photo here” leads to an image of what seems to be a head-and-shoulders photograph of the boyfriend. Clicking again, though, reveals the same man in slightly different poses, as if each new frame is the frame of a kind of animation, showing the man turning to his left, toward his girlfriend, an opening for a possible connection.

There’s also an image of the logo for 20th Century Fox, the film studio. This appears in a sequence that plays out in the upper part of the section on the right side of the screen, following the close-up portrait. It is preceded by intertitles reading:

So,

last time we met

when…

And you promised.

Then:

Me too.

DO YOU

Then the section divides into four small frames, which read, “LIKE / MY / NEW / DRESS?” In turn, these lead to “Who asks you? / TOGETHER FOREVER / We’ll start a new life.”

At this point, the logo appears.

It’s easy to read this image, forever associated with Hollywood moving image credits, as the intended endpoint of the work as a whole. However, because the user is given the option to advance through different frames at different rates, many users would not encounter it as the final frame of the work. Instead, it could be read as a kind of aside. If the adjacent frames suggest a kind of romantic, youthful optimism (“TOGETHER FOREVER”), then the inclusion of this logo could be taken as a sort of wink at the typical Hollywood ending.

The frame immediately below the image supports this reading:

will you marry me

Then

TOMORROW

Then, in a great rush

No, better next month after holidays and the weather must be better. Yes next month. I’m happy now.

In other words, no.

Through all of this, the couple in the left-hand frame sit unmoving. The window still flickers above them, on an endless loop. It is the opening image of the piece, and time has passed but it is uncertain as to whether the image is meant to refer back to the moment at the beginning of this conversation or if it is intended to convey the sense that time is passing and nothing has changed.

The use of frames in My Boyfriend Came Back from the War thus creates a spatial and temporal montage in which images and texts are juxtaposed in both time (by loading new frames in sequence) and space (by loading frames adjacent to one another in a split screen formation), partly under the user’s control.

In Austin, Texas, I saw the filmmaker Jean-Paul Gorin give a talk in which he said, "In France, we think of everything in terms of time. We have before and after heartbreak. In the US, you think of everything in terms of space. You have south and west of heartbreak." My Boyfriend Came Back from the War marries these two types of memory, the temporal and the spatial.

HYPERTEXT

The problem of memory is at the origin of the development of hypertext: the fear of losing knowledge and the urge to organize the world.

After coming back from World War II, scientist Vannevar Bush articulated the sense of uncertainty and aimlessness that came along with the end of a campaign, in this case, the Manhattan Project:

This has not been a scientists’ war; it has been a war in which all have had a part. The scientists, burying their old professional competition in the demand of a common cause, have shared greatly and learned much. It has been exhilarating to work in effective partnership. What are the scientists to do next? 13

To be a part of the scientific wartime effort was to be a part of something meaningful, after which the ordinary contours of everyday life might understandably have been hard to accept. Luckily, Bush glimpsed the possibility of another great challenge on the horizon to lend meaning to existence: the mountains of information (generated, in part, by wartime research) that could no longer be easily grasped by the individual scholar. How could this knowledge be organized?

Bush’s article “As We May Think” famously described a filing system called the “Memex” that was to offer an analog technological solution to this conundrum. It argued that the typical system of classifying data is not suitable for human modes of thinking. “When data of any sort are placed in storage, they are filed alphabetically or numerically and information is found (when it is) by tracing it down from subclass to class.” Bush argued that a more linear or perhaps narrative mode of organizing information might offer the best results. Rather than trying to organize knowledge according to rigid hierarchies, researchers could create subjective, associative trails across a series of documents. “Any item may be caused at will to select another immediately and automatically… The process of tying two items together is the important thing.” This early articulation of a non-hierarchical means of indexing knowledge within computer culture laid the groundwork for the later development of hypertext. It privileged the cultural form of the narrative (loosely defined) over that of the database and it positioned knowledge and memory as subjective processes.

The concept of hypertext was brought to its most important realization in 1989 at another scientific nuclear facility. At CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, which now hosts the large hadron collider, Tim Berners-Lee wrote a proposal for an approach to the problem of institutional memory at a large scientific organization with high staff turnover. “Information is constantly being lost,” he warned. The solution he prescribed was the use of hypertext, or “Human-readable information linked together in an unconstrained way.” Here, again, hypertext is proposed as a solution to improve the computer’s ability to support human memory.

While Berners-Lee waited for news about his hypertext proposal, he attended a local performance of the play Goodbye, Charlie, in which a womanizing man is murdered by a jealous husband and is reincarnated as a beautiful blond, played by Nancy Carlson, an American programmer working for the World Health Organization in Switzerland. (Berners-Lee was also something of an actor; his favorite role was that of Nana, the nursemaid dog in Peter Pan, thus crossing boundaries of species as well as gender.) Carlson caught his eye, and they began dating; a marriage proposal soon followed. By the following year, both proposals had been accepted: The two were married, and Berners-Lee named his system the “World Wide Web.”

What’s fascinating about Berners-Lee’s hypertext proposal is that it departs markedly from Bush’s prior critique of the computer’s organization of knowledge. Where Bush argued that the typical organization of knowledge is incompatible with the structure of our brains, which use countless lateral connections to connect thoughts and memories with one another, Berners-Lee argued that the problem with “trees,” as he labeled hierarchical knowledge systems, is that they fail to “model the real world.” The example Berners-Lee gave of the “real world” is a discussion group that drifts from one topic to another. This is not Bush’s real world of the human mind but a real world of shared discourse, which suggests that the web was defined as a social medium from the beginning. Already, though, the phrase begins to hint at some of the truth claims that would later be made on behalf of Big Data:

Imagine making a large three-dimensional model, with people represented by little spheres, and strings between people who have something in common at work.

Now imagine picking up the structure and shaking it, until you make some sense of the tangle: perhaps, you see tightly knit groups in some places, and in some places weak areas of communication spanned by only a few people. Perhaps a linked information system will allow us to see the real structure of the organisation in which we work.

In other words, Berners-Lee grasped the web’s potential as a tool for surveillance. Hypertext’s compatibility with the associative, nonlinear structure of discourse made it a valuable tool for the empirical analysis of social behaviors, in this case allowing the relationships among employees to be mapped and organized.

Thus there were already two kinds of memory at stake in Berners-Lee’s proposal: the memory of the users of this hypertext system, who would use it to make lateral connections across a voluminous body of research, and the memory of the all-seeing analysts charged with organizing it.

The former kind of memory, the social memory facilitated by hypertext, was always central to Lialina’s understanding of the function of net.language. Only later, as the mechanisms of algorithmic control became more powerful, did this come into focus as an explicit position of resistance.

A VERNACULAR WEB

At the time of Berners-Lee’s proposal, there was already commercial software on the market to support hypertext authoring. HyperCard, developed by Apple and included with all new Macintosh computers in the late 1980s, made this kind of nonlinear writing accessible to wider audiences. Eastgate System’s Storyspace, designed by Jay David Bolter and Michael Joyce and released in 1987, found particular traction among artists and writers for its ability to map out complex multilinear pathways. A number of works authored with Storyspace were distributed on floppy disk or CD-ROM. Berners-Lee was well aware of the work being done in the field and his 1989 proposal made a specific reference to a hypertext conference at which Bolter and Joyce presented.

The author Shelley Jackson is among those who embraced Storyspace as a writing tool, using it to author the celebrated hypertext work Patchwork Girl, which was published on CD-ROM. In this work, drawings of parts of a girl’s body open out into complex, interwoven narratives. The story draws on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and in it, users can read journal entries describing the process of creating the monster:

I have had plenty of time to make the girl. Yet the task was not so easy as you may suppose. I found that I could not compose a female without devoting several months to profound study and laborious disquisition.

Another strand of the work begins with an account of the day the monster “parted for the last time with the author of my being, and set out to write my own destiny.” Thus the story of the creation of the monster can be understood as an allegory about the role of the hypertext reader, constructing meaning and identity from a fragmentary text.

Formally, Patchwork Girl is quite similar to a later work by Jackson titled my body – A Wunderkammer (1997), which was her first hypertext work made for the browser rather than CD-Rom. Clicking on a white-on-black woodcut drawing of a girl’s body brings the user to pages dedicated to specific parts, with written anecdotes and meditations accompanied by woodcut-style portraits. In place of the elaborate, carefully crafted fiction of Patchwork Girl, My Body offers a more directly autobiographical approach.

Thus Jackson’s most celebrated hypertext work for CD-ROM was a fiction that is readily understood as a work of literary theory, while her first work for the web used a very similar formal language to elaborate a personal memory much more directly. This difference in approach can be understood in relationship to the conditions of circulation and reception surrounding the offline and online hypertext work.

The CD-Rom presented itself as a highly finished object, discrete; it was to be consumed in the private space of the desktop, with the author separated from the reader by layers of packaging, a jewel case, a publisher, an envelope that arrived in the mail. Much was made of the way that hypertext changed the reader’s role, making it more active, but the format still created a division between the role of reader and that of author.

Visiting a web page, on the other hand, meant making a connection with someone’s server and accessing files from it. In the days of dial-up, when this connection might have been made via the home phone line, it perhaps felt even more like connecting with a person.

Perhaps more importantly, the web was a space where many readers were also authors. If hypertext allowed readers to take a more active role, the web continued this trend by fostering a sense of connection between reader and writer and giving readers the means to self-publish. When Jackson made work for the web as opposed to the desktop, she would have been aware that she was addressing a public made up of fellow writers, many of whom would have been relating autobiographical stories. Thus it shouldn’t be surprising that Jackson’s shift from the CD-ROM to the web occasioned a shift to the first person and to the author focusing on her own story, taking her place as a part of this hypertext-writing and reading public.

Lialina has written about the particular importance of personal memory on the early web:

I look through a lot of old… homepages every day, and see quite [a few] that are made to release stress, to share with cyberspace what the authors can't share with anybody else, sometimes it is noted that they were created after direct advice of a psychotherapist. Pages made by people with all kinds of different backgrounds, veterans among them. I don't have any statistics [as to whether] making a home page ever helped anybody to get rid of combat stress, but I can't stop thinking of drone operators coming back home in the evening, looking for peeman.gif in collections of free graphics, and making a homepage. 14

The web was always a space for memory and autobiography, and the net.language facilitated this.

A similar transition to a first-person, and seemingly autobiographical, mode of address can be found in Lialina’s own trajectory. Prior to her life as a net artist, Lialina had been a co-organizer of the Cine Fantom experimental film club in Moscow, which was founded in 1994 to expand the Parallel Cinema movement, a current in Soviet underground cinema that began in the 1980s. In 1995 the club received a gift of a computer from that dear Uncle from America, the Soros Foundation. “Windows, 3.11 if I remember it right... I immediately started to make posters for our program in Microsoft Word,” Lialina recalls. Alongside this promotional activity, though, Lialina soon began to explore the use of the web as a context in which to share Cine Fantom’s archive of Parallel Cinema, a form of lo-fi underground cinema that positioned itself as a radical, though not explicitly political, alternative to mainstream media. In September of 1996, the same month in which My Boyfriend Came Back to the War was published, Lialina made a presentation about her efforts with the Parallel Cinema archive at the new media organization V2 in the Netherlands. “Olia Lialina (Moscow): CINE FANTOM. New life on line… She will be talking about the opportunities and problems of putting time-based arts online.” Thus, Lialina was using the web as a site of memory even before her first artwork. By the time of the V2 meeting, Lialina had already transitioned from “putting time-based arts online” to making work for the web and from putting public archives online to creating personal narratives to share with other web users.

MEMORY AND THE INTERNET USER

In particular, the story related by Lialina in My Boyfriend Came Back from the War evokes the affective experience of being an early internet user and a young woman in Moscow in the mid-1990s. As such, it can be understood in a broader tradition (alongside Jackson) of feminist writing that connects individual experience with social history and the power of discourse with the crushing realities of material circumstance, as described by Laura Sullivan in a 1999 discussion of the hypertext memoir.

Women’s autobiographies can connect the feminist call to value women’s personal experience with both the postmodern belief that discourse produces our understandings of our “selves” and the materialist feminist recognition that our experiences are situated in history. 15

Lialina’s work speaks very powerfully from a particular moment in history.

Netscape was formed in 1994 and by the end of the year its Navigator web browser was by far the most popular with the 13.5 million internet users worldwide. In 1995, the company went public, closing its first day of trading with a valuation of $2.9 billion despite a total lack of any revenue. This marked the beginning of the dot com boom, in which investors poured money into questionable internet companies based on wildly optimistic visions of the earning potential of the early web.

The second battle of Grozny, in August of 1996, precipitated the end of Russia’s first disastrous war in Chechnya. Faced with an unexpectedly robust guerilla resistance, Russian soldiers waged war indiscriminately, killing and displacing hundreds of thousands of civilians. The war was deeply unpopular with a now-independent press, and public sentiment against it ran high. A ceasefire was signed on August 30.

While situating its narrator in history, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War also took care to consider the user's participation in its narrative. The work constructs the user's point-of-view by making a visual allusion to the window of a house. The user therefore takes on the role of a voyeur, looking in on this awkward but intimate encounter. At the same time, the use of frames is an absolutely recognizable element of the web of the late 1990s. Lialina has commented on their iconic quality: “Frames create a very recognizable visual pattern. In general when graphic design makes reference to web design the frame layout is commonly used.” Thus the use of frames constructed the audience as both voyeur and web user.

The voyeur is a role typically associated with cinema; the voyeur watches, while the computer user – the computer user acts. But by placing the user on the other side of a window, Lialina made it clear that they were not in fact effecting any change on the overall outcome of the narrative, a sense of stasis that was reinforced by the unchanging image of the estranged couple.

One specific possibility offered by hypertext fiction (or interactive narrative in general) is that there can be many pathways through a story, that the user is given some level of agency to model possible outcomes. In the case of MBCBFTW, this agency is moot; the events depicted in the work have already happened and are merely being uncovered by the user-voyeur.

It seems incongruous that a work so closely associated with the euphoric early days of the web would have such a melancholic air. But MBCBFTW is very much a work of the web, despite its tone. In fact, it is intimately bound up with one of the most important uses of hypertext, and of the web – narrating the past. Even if the user is unable to change the outcome of events, there remains the possibility to rewrite events of the past through remembering them – after all, the web page itself is a kind of mutable performance and one that can then be taken up and remade by other computer users on the web.

And it has been remade. Lialina’s website now hosts a list of links to remakes and remixes, some made by friends and others by strangers. One version by Ignacio Nieto, which Lialina describes as especially dear to her, pays tribute to 44 young Chilean soldiers who died tragically after being sent, ill-equipped and untrained, on a hike into a fierce mountain blizzard. Another cheekily translates the project to a wearable slogan: “My boyfriend came back from the war and all I got was this stupid t-shirt.” Thus Lialina’s project is re-performed and remembered in other contexts, while offering a format within which other users may narrate their own memories.

While this openness to re-interpretation may not have been explicitly stated in the work, it’s important that the last frame to appear in the very bottom right of the piece contains Lialina’s email address, making explicit the connection between writer and reader, artist and audience.

The Vernacular is Political

Today, the cause of free speech is very much at the forefront of public debate about the internet. The net is commonly used to wage symbolic violence and to plan real violence. At the same time, it is constantly monitored for evidence of a willing consumer or a bad citizen. These forces limit and structure the range of potential expressions that can be made on the web and they define limits of speech and expression. As such, they are hotly contested.

While extremely worthy, this struggle seems always to be defined by a focus on content, or on infrastructure. The net.language developed by Lialina and employed to poetic ends in My Boyfriend Came Back from the War is also under attack:

Web browsers developing in the direction of operating systems are leaving the idea of interlinked documents behind. Though hypertext is technically still there, it is not important any more, neither is surfing or linking. The web consists mainly of application interfaces where users activate functions.

These constraints also impose limits on net.language, hindering the web’s usefulness as a space for social memory, and they should be just as hotly contested. To advocate for these aspects of net.language is also a political struggle.

Walter Benjamin wrote that “Every expression of human mental life can be understood as a kind of language.” For Benjamin, this applied not only to speech, but also to artistic media and public institutions:

It is possible to talk about a language of music and of sculpture, about a language of justice that has nothing directly to do with those in which German or English legal judgments are couched, about a language of technology that is not the specialized language of technicians.

For Benjamin, these languages were not merely the media through which underlying ideas could be expressed. Rather, he argued, “the mental being of man is language itself.” All human thoughts are expressible in language, or perhaps no thought can form that cannot be expressed in language. If there is no thought outside of language, then the invention of new languages may expand the realm of thought itself, affecting all mental processes, memory included.

This was the opportunity opened up by the development of hypertext and its further elaboration on the web. This net.language, this lateral, associative writing practice, which facilitated the sharing of first-person autobiographical accounts in multilinear form, offered a glimpse of a new social imaginary based on an understanding of the fragmentary subjectivity of both writer and reader, in which memory is seen as an open-ended and collaborative process, facilitated by the non-hierarchical and expressive potential of hypertext.

This possibility is threatened by the Big Data business model that aims to limit all online expression to the algorithmically legible, claiming that this will reveal the real us, our unified essences, the workings of the social order, our place in it, our value to it. Under Big Data, memory is neutral and mechanistic, to be measured only in terabytes.

When Lialina speaks of net.language and employs this language in her artistic practice, something like this is what's at stake. Net.language is the language of the user, a figure of fragile and radical promise, constantly under threat.

Header image: Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, 1996. Photo: Franz Wamhof.

--

1. Josephine Bosma, “Olia Lialina interview Ljubljana,” <nettime>, 8/5/97, web. http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9708/msg00009.html

2. Marina Grzinic, “An Insider's Report from the Nettime Squad Meeting in Ljubljana, 22 & 23 June 1997,” Telepolis, 6/19/97, web. (The title is apparently an error, as the meeting took place in May). http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/4/4071/1.html

3. Christian Metz, Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 3.

4. Bosma

5. Josephine Bosma, "Vuk Cosic interview: net.art per se," <nettime>, 9/27/97, Web. http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9709/msg00053.html

6. Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, London: Harcourt, Inc., 1977, 3.

7. Olia Lialina, "Prof. Dr. Style:Top 10 Web Design Styles of 1993 (Vernacular Web 3)," 2010. http://contemporary-home-computing.org/prof-dr-style/

8. In 1994, Netscape Navigator became the first browser to display web pages as they loaded on the fly, with text and images appearing as they downloaded. With other browsers, a page would remain blank until all elements were loaded.

9. Metz

10. Landow 1992

11. Laura L. Sullivan, “Wired Women Writing,” Computers and Composition (16:1, 1999), p. 31.

12. Eisenstein, “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form,” from Film Form 1949.

13. Vannevar Bush, "As We May Think," The Atlantic, July 1945, Web. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

14. Olia Lialina, "Rich User Experience and the Desktopization of War," http://contemporary-home-computing.org/RUE/

15. Laura L. Sullivan, “Wired Women Writing,” Computers and Composition (16:1, 1999), p. 31.