The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Jason Huff: Custom software and scripts are common tools you use to create your work. In 2013 you open-sourced Corrasable, a web service you created that puts linguistic processing libraries together “to assist in analyzing text and converting it into alternate representations.” What does it mean for an artist to share their process? Why is it important for you to let other artists or programmers have access to Corrasable?

Damon Zucconi: I'm interested in forms of production where publishing is more of a side effect, rather than a terminal state, and that tends to necessitate working out in the open. But this interest stems less from the ethics of open source and the "bazaar" models of collaboration that are wrapped up in it, and more from how process at large becomes part of the public record.

With most tools, there is a boundary between states, consistently delineating the space between what is “complete” and process at large. This boundary also tends to be the line between what is public and what is private. When every aspect of one's process is online, a native connectivity simplifies the combination of what were previously separate elements. The distinctions between those states of resolution begin to break down.

In publishing an API, as in the case of Corrasable, I think of it more in the sense of building material primitives—works as small units of meaning that I can reassemble into new works— rather than exposing something for others to use. What I'm trying to do is to reveal new material possibilities to myself in a kind of self-centered platform-thinking: objects made not to further predefined goals, but to unlock possible futures.

The more of these systems I build, the more I see synergistic effects appear. Those effects aren't anything novel. Most companies think of their platforms in this way, and, similarly, most artists take the time to form a language of gestures, that, once developed, becomes a codified "approach" that reaps similar benefits.

For instance: Corrasable exposes an endpoint for doing phoneme segmentation, upon which I developed a tool for rudimentary speech synthesis, which then has become the object of some recent video work. So there's this interesting chain of production and dependencies that currently terminates in some videos, but this was never really a goal, just a consequence of opening successive doors. It's interesting for me to think of an art object as an operational assemblage of previous works.

I do pay attention to the use-value others uncover in the work, as this frequently alters meaning, or maybe guides my hand later on. Anything made with a kind of structural openness is going to have new uses found for it, but both the consequences, and the fact that there are consequences at all, is somewhat adjacent to my intent.

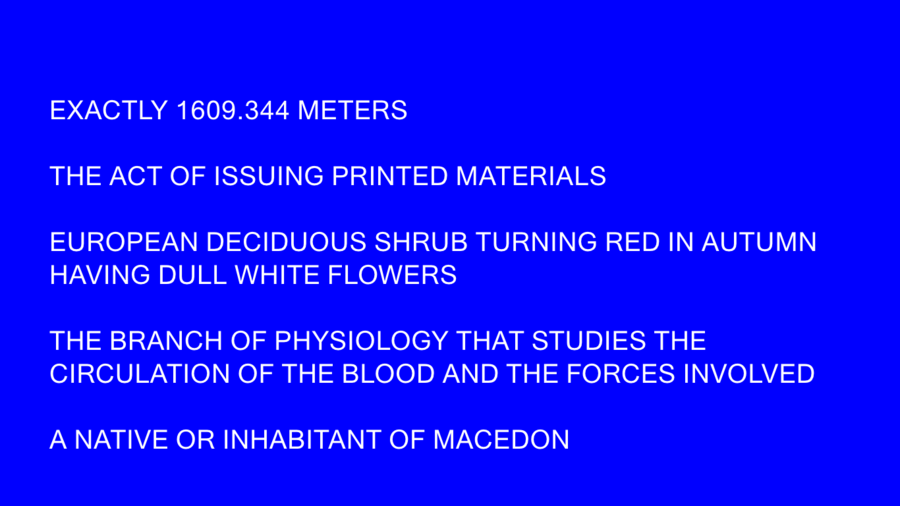

Damon Zucconi, dictionary.blue (2016)

JH: You had a prolific presence in the surf clubs (Nasty Nets and Supercentral) and related sites (Club Internet and Are.na) of the early 2000s, taking on the role of author, curator, and engineer. How do you see surf clubs influencing the wider net culture’s evolution, including your own?

DZ: At the time, surf clubs felt more like contributing motion to some disembodied entity—a type of collective wayfinding, or figuring out. "We can all agree on X, so how do we get to Y?" There's this group-decision making that goes on that's unspoken, and you never do get to Y.

The structure of a blog—that verticality of posts stacked on one another—helps in furthering this idea of a linear kind of progress. You can really see how the structure imposed by WordPress as a publishing tool plays out when taken up by artists, with "surf clubs" as a direct reflection of a closed-registration, multi-user, linear blog. The closed nature also foregrounds a kind of performativity that felt very present.

With Are.na, aspects of its structure were designed to combat some of those tendencies, while playing up others. By emphasizing the horizontality of connections, instead of a verticality, you favor multiple contexts and open yourself up to having a piece of information's meaning altered through proximity to others. And it tries to distil that notion of collective wayfinding—you visit and post to get a sense of what others are up to and to solidify what you are working toward.

The dominant publishing technologies tend to dictate the kinds of communities that evolve under them. But needs for specific communities also necessitate the creation of new publishing tools—Are.na was born, in part, to fill the hole that the death of del.icio.us left. By creating publishing technologies, you manifest the new, the public binds to it and makes it their own.

JH: Your work has been described as a “more structurally complicated picture of time” by the writer Gene McHugh. What do you think about time’s structure? How does it appear or disappear in your work?

DZ: The systems that govern the division of time, lending it a structure, always point outside of themselves. They aren't self-contained, logically consistent things. They embody distinct worldviews or cultural histories in modes that are political or memorial. Or they might be observational, describing motions of the moon or sun or both. And these systems alter the flows and rhythms of our life and give our temporal environment a particular kind of shape. I'm curious about the ways in which those things can be subtly reframed to reshape one's personal temporal environment.

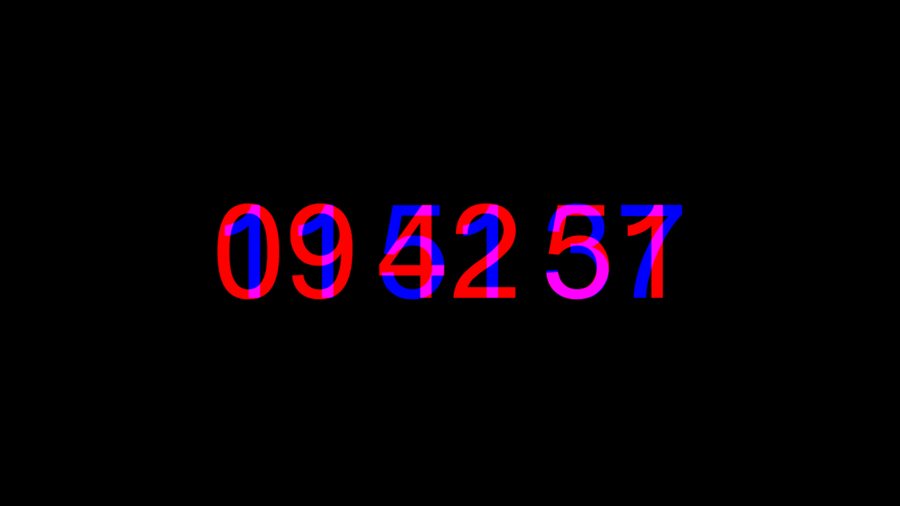

I recently published a piece, Coordinated Mars Time, that overlays the mean solar times of both Earth and Mars, in corresponding blue and red. One watches as the seconds fall in and out of phase—the “coordination” is in number only, not in the absolute value of the units. You can feel the rhythm of the standard second slip out from under you as the colors mix to form composite figures. And so the differences in the size and length of a solar day on each planet takes on a form that can be felt.

Those kinds of manipulations are ways of decoupling you from your subconscious sense of a standard's value; this sense that's implicitly held but imprecise: "one Mississippi, two Mississippi." I understand some of the works as gestures that get in between you and how you measure the world in relation.

Damon Zucconi, Coordinated Mars Time (2016)

JH: In your last exhibition at JTT you included print-on-demand copies of six pre-existing novels re-published with every word misspelled. Experiencing those books first-hand was disarming and interesting. I’m always interested in the choice to take something offline, into the physical world. What lead you to print out copies of the books, instead of presenting them online?

DZ: I imagine that, ultimately, some of those books will circulate divorced from their original context. Forgotten, passed on, lost and found. Those prospective owners will have to deal with the objects on their own terms: some liminal state between an existing piece of recognizable "intellectual property" and something else entirely; something novel in the world.

It's easier to wash your hands of something when it’s offline. The operative word when publishing on the web is "host." You host the content on your server, and when someone requests it, your presence as a host is always implicit.

Maybe this points back to your question about time. In step with making an object, one gains the responsibility for it; that novelty, the something "extra." One has to consider how it will age, change owners, deteriorate, break, be replaced, stored, misremembered.

With the books, I was thinking of Borges' Tlön: "[…] the dominant notion is that everything is the work of one single author. Books are rarely signed. The concept of plagiarism does not exist: it has been established that all works are the creation of one author, who is atemporal and anonymous."

Those books are me making serious on this proposition and muddying my responsibility to being an object-maker: bringing a new object into the world without a commitment to novelty.

Damon Zucconi, On Bieng Bule (2016)

JH: You mentioned this idea of revealing “new material possibilities” to yourself in your work and the concept of “self-centered platform-thinking.” Can you speak more to those ideas and the potential to “unlock possible futures” for yourself?

DZ: Materials are a question of agency. It’s about gathering up some quantity in the world and instrumentalizing it so it can be of use to you. One could say something like "paint is an instrumentalization of color." You can look at any quantity in the world with this same frame of reference to create a new material.

That perspective allows one to look at something like a CRUD application or scraping a dataset with an eye towards materiality—as activities which are fundamentally about gaining agency. This is maybe why I never totally understood the arguments that assert the immateriality of digital practices.

This is also why I'm so interested in building different types of archival and content management systems for my work. Archives consolidate and in doing so they create a basis with which to approach the future. One's own work is made material in the aggregate in this sense.

In building platforms, you rely on an ambiguous position to the future. They exist to support activities which haven't yet been anticipated. And there's this tendency to think about digital platforms as these big things that depend on the unknowns that a public, specifically, brings to bear on them to function. But I'm more interested in the self and the studio. Of turning inward but taking with me that openness and stance in relation to the future that they enable.

screenshot from Most Common Nouns (2016), web application

Questionnaire:

Age: 30

Location: New York

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I started making websites before I owned a computer, soon after discovering the Web at my public library. I needed something to put on them and so I began to make art, as content to fill them with.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I studied Interdisciplinary Sculpture at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I’ve previously worked as a web/print designer and currently as a software engineer.

What does your desktop or workspace look like?

Lately, as I work I usually just screen capture interesting parts of what I'm doing and post them here to keep tabs on myself: http://atlas.damonzucconi.com/studio

Header image: Damon Zucconi, Northern Gesture (2009)