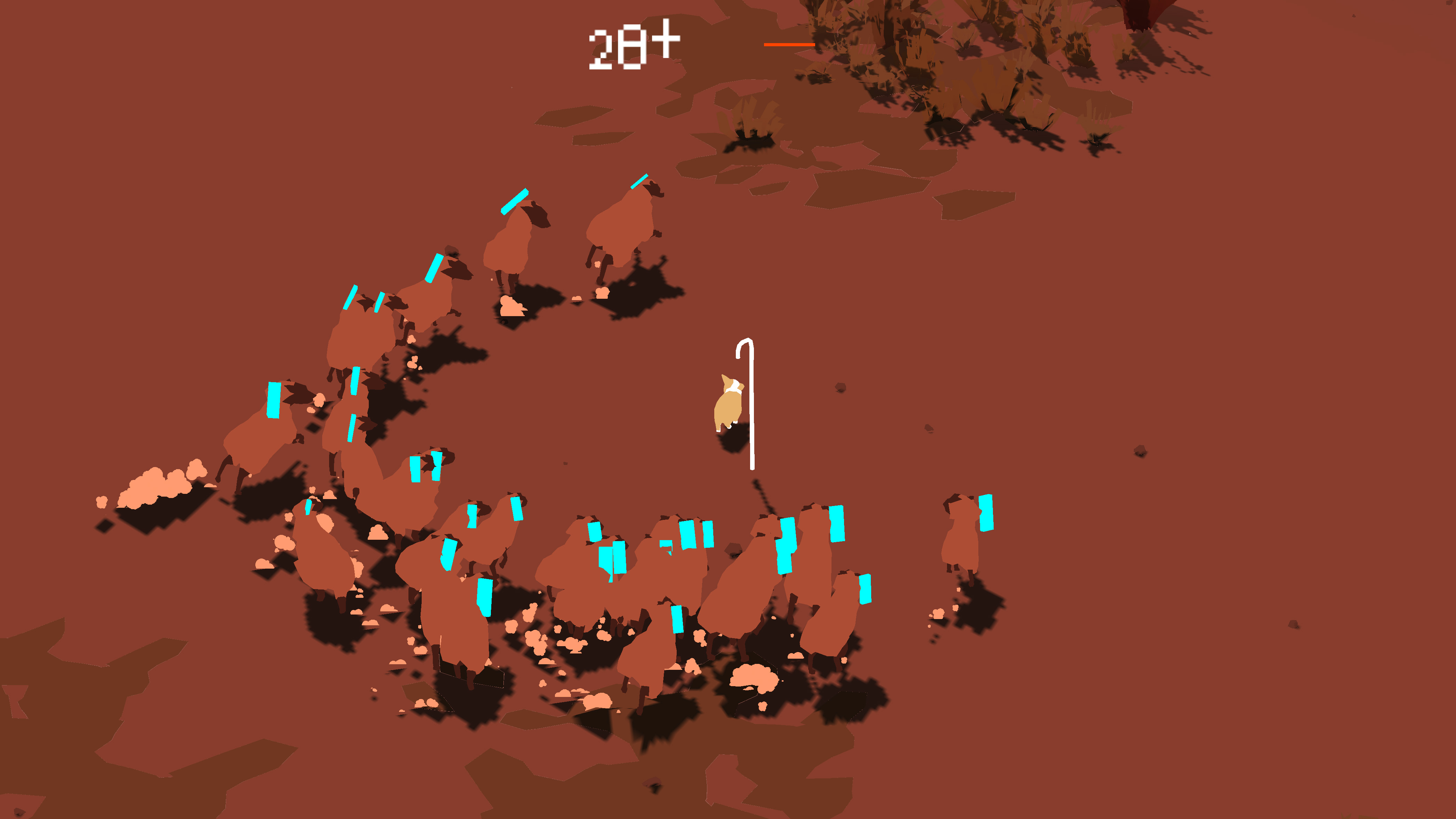

On the splash page of Ian Cheng’s Bad Corgi, a Serpentine Gallery digital commission, I watch a corgi, a herd of sheep, and a white shepherd’s crook totter across a red, rocky landscape in a madcap dance. The animals are mesmerizing, rendered in dense, saturated colors, like razor blade cutouts from the Pantone book come to life. I am to pick between three modes: 100% Perfect Grazing, Patchpusher, or Herd Gazing.

I start off with 100% Perfect Grazing. In the first minute, I am running. The corgi is always running. Corgis are tough, small dogs that have been used to herd sheep for centuries. My task is to use the touchscreen to corral the corgi and the sheep. I trace clean lines around the animals and they run within these boundaries. The corgi clips some brush. Text flashes: Bad! My first infraction. Though I try to maneuver the dog with some deftness, it runs across patches of light green that appear at blistering speeds. Within minutes, I drop from the grace of 100 percent to 0, to -454 percent. Very bad!

I am not yet sure what I am meant to do in this app, but I already hate this dog. I pair my index and middle finger to fling it from one end of the screen to another. I try to boomerang it toward the escaping flock. The corgi, suddenly, will not go. It spins in place under my index finger. I press harder against the screen and it twitches, riven by unseen forces. Its head expands and contracts, and it bursts into a spray-fall of tiny white, gold, and brown squares that coalesce into corgi, again. The corgi—it does not feel like my corgi—scampers away from me, down a dirt path. I set the iPad down, and go outside to stamp around in the snow.

When I start again, my errors compound and multiply. The sheep sense my approach and evade me. A fire hydrant, then a teapot, then a tombstone bob and weave across the corgi’s path. Wolves slip between the shadows of my stupid charges. Rabbler sheep split and disturb the herd. My score plummets into the negative thousand percents. Desperate, I circle the remaining two sheep in sight; one is named Shy; the other, Shemwel. Dog, sheep, all meet a fiery end. It’s only been an hour.

Bad Corgi, a “shadowy mindfulness app for contemplating chaos,” subverts the user at every turn. It seems to have a mind of its own. As an eager player, my inherent inclination is to fix, to reverse the war of attrition through mastery. But I must accept the corgi’s—the system’s—self-destruction and ruin. This is a difficult proposition to allow. On some level, I think my hard work and skill should pull my corgi through to an unspecified triumph.

According to Cheng's bio, he "sees his simulations as a kind of neurological gym in which art becomes a means to deliberately exercise the feelings of confusion, anxiety and cognitive dissonance that accompany moments of change." This gives me pause, because all games are, in fact, neurological gyms. Systems design for almost all games and simulations factors in the affective life of the user. All play, indirectly or directly, with the user’s emotions (particularly the negative valences, from frustration and anger to irritation and boredom), whether this intention is explicitly built upon or not.

Further, when a sophisticated understanding of affect (and of how the user needs to be manipulated, bent, made to feel in or out of control) is built into a game world, it is often carefully concealed. In Bad Corgi, the reveal, to the user, of the designer’s awareness of the manipulation feels more irritating than a dog built to disobey. Why?

For one, this user can’t stand interruptions to the bliss of immersion, because I want, above all, to be sunk into the system. I do not want continual reminders of the system’s inimical position, its coded hostility and betrayals. I let go of the screen to watch the corgi run. It gets back on track, nosing the sheep into order, avoiding trampling bushes on its own. The system seems to work better when I am not involved at all.

A resistant, unpredictable set of rules tests our collective trust of algorithmic systems, whether sweetly predatory or ruthlessly extractive. When the corgi strays too far, the shepherd’s crook snaps it back with a thin, glimmering white line. Imagine if these algorithmic guides were always clearly drawn for us, manifested, visible. We could see tiny hoses siphoning off our data from us every moment as the day is long. We could watch all the platforms, like big blue shadows, molding themselves in real time to fit the shapes of our bodies, to echo and mirror our expression.

For now: I don’t want to dwell on this. I pick Patchpusher Mode. I send the corgi barrelling out to clear trees and brush; it gains momentum as it rolls shrubs into massive spheres. I think of a priest clearing a ritual ground. The leveling is tactile and satisfying. Even when I’ve reached the goal, I continue to clean the ground in obsessive circles, sweeping. I turn inward, slipping from anxiety to calm. There are meditative modes to be discovered in every game, whether cruising Los Santos in Grand Theft Auto V or fishing in a bootleg Russian MMO.

If Cheng meant for me to embrace anxiety as productive, perhaps he also meant for me to find a kind of peace. In Herd Gazing mode, my corgi runs fluidly alongside the sheep. The goal, if there is any, seems to be simple: run. Observe. I have some remove to marvel, to examine detailed gestures. At dusk, the sheep turn butter yellow, then orange, then gray against the red rock turning violet. Their shadows deepen from slate to midnight blue. They kick up little clouds of dust.

I feel my heart rate slow, as my peripheral attention trains on these multiple moving streams. There is mindfulness in learning to curve the screen, in allowing my fingers and wrist to learn how to flow and snap the corgi in pleasing arcs. I trace precise circles on the screen, pulling landscape about. I am subsumed. Rear, halt, accelerate, flow. The corgi feels more like it is mine.

Coyotes tag along to run next to us. Unease creeps in. I remember the shadow figure running alongside the protagonist in Wizard of Earthsea: a constant black dot on the horizon. I think of the couple bound together by a red rope in Takeshi Kitano’s film Dolls. Anxiety, fear, like a person that follows you, that is quiet by your side, tied to your waist. Herd Gazing mode ends unexpectedly in white, blinding explosions; the sheep dissipate into puddles of ochre, Nickelodeon neon green. Disaster.

Just as the first mode made me think of how algorithmic binds are concealed, the second and third make me consider the hidden imperatives of mindfulness apps. I am a half-hearted user of Headspace; despite earnest attempts and resets, I cannot sustain a meditation routine. Isn’t mindfulness—an ability to quickly disassociate and detach from stress, pain, and suffering—a tool of neoliberal self-care, self-correction, self-management?

Bad Corgi is exceptional for interrogating the promise of digital smoothness, of a landscape of past and present that is all clean and free. In it, mindfulness is crucially linked to digital smoothness; just as a game is praised for convincing one of the illusion of flow, an app cares for you by helping you iron out your worries. Digital smoothness cradles and buoys one from one disaster and trauma to the next. Bad Corgi refuses such insidious smoothness. It wants me to get upset, to remember, to take responsibility.

Any suggestion that the algorithm will solve difficulties is an illusion. The algorithm will not care for me; the future will bring more trials and assaults and injustices. I can only run forward to meet them.

All images from Ian Cheng, Bad Corgi (2016). Still images from iOS app.