This text was originally commissioned by ICP and Printed Web and published in Printed Web 4. It appears in a slightly edited form below.

The yarn is neither metaphorical nor literal, but quite simply material, a gathering of threads which twist and turn through the history of computing, technology, the sciences, and arts. In and out of the punched holes of automated looms, up and down through the ages of spinning and weaving, back and forth through the fabrication of fabrics, shuttles and looms, cotton and silk, canvas and paper, brushes and pens, typewriters, carriages, telephone wires, synthetic fibers, electrical filaments, silicon strands, fiber-optic cables, pixeled screens, telecom lines, the World Wide Web, the Net, and matrices to come.

– Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture, London: Fourth Estate, 1998.

**

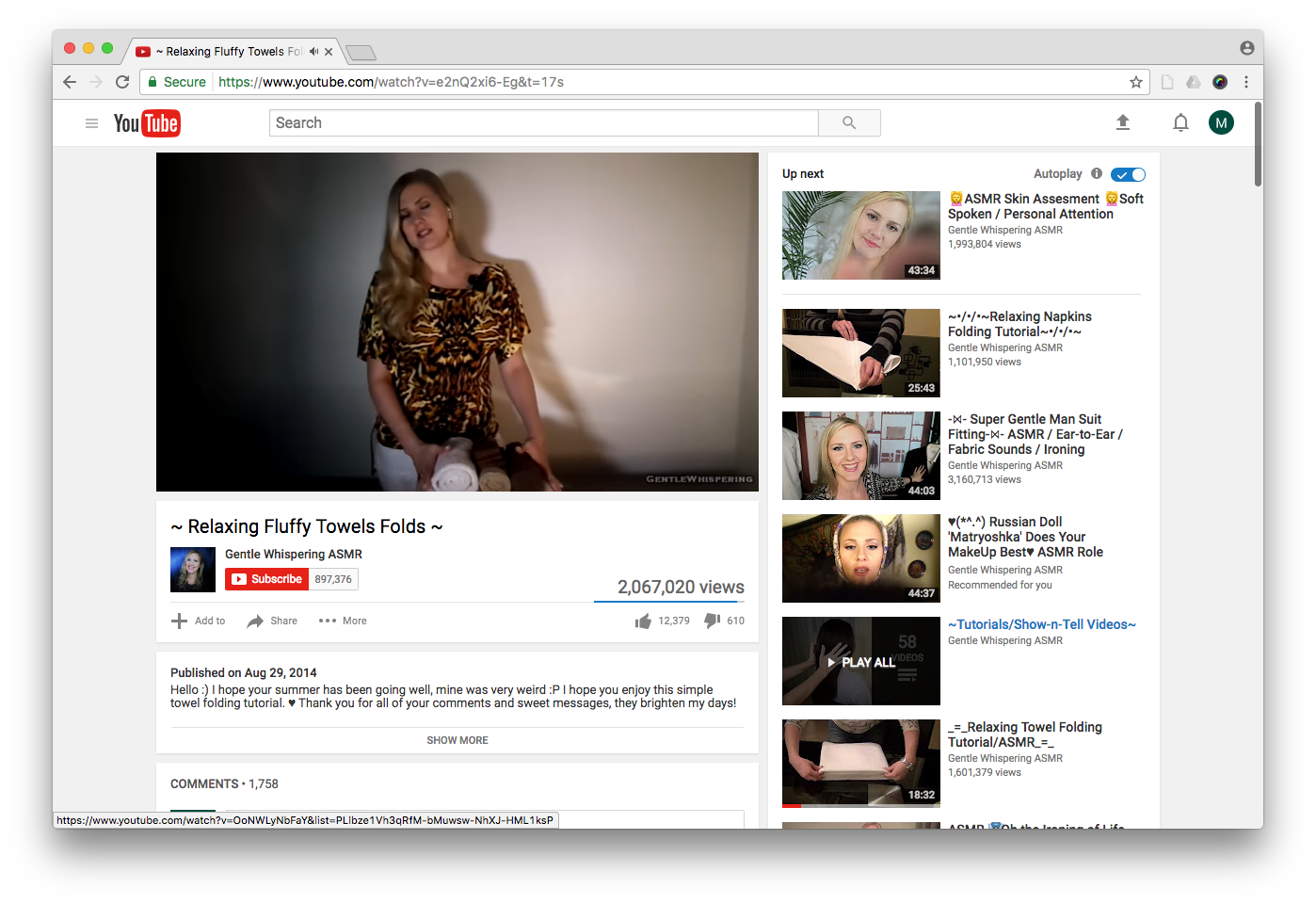

"Hey guys! :D I was getting allllooot of requests on doing more folding so I decided to try and make it into a role play sort of a video."

The video begins with a fair-skinned woman standing before a dark wooden table stacked with several neatly rolled towels. She tells us that we will be watching a tutorial, and that we will learn how to fold towels in a tidy and decorative fashion. The camera lingers as she strokes and caresses the towels; she speaks in a soft voice, as if babying the viewer.

The video, posted from the popular YouTube account GentleWhispering, seems to address an infantile viewing subject who couldn't possibly fold their own towels, or likely even use the toilet unassisted. The fold has no instrumental purpose here apart from offering sensual pleasure to this viewer. The instructions delivered by this maternal figure become a kind of drowse-inducing wash; any information that happens to be relayed is merely incidental, ready to be discarded. The video's description labels it as "for entertainment purposes only," and the comments focus on the woman's voice, her body, and the aesthetics of the video--only rarely does someone mention towel folding.

Although she is carefully composed on camera, GentleWhispering's comments offer a glimpse of the strain she is under. Her camera broke, the apartment above her flooded, and she felt depressed for a month. Even a successful vlogger lives a precarious existence.

**

Deleuze used the fold as a way of thinking about divisions that also connect, enabling multiplicity and oneness; enclosures that also open out to the world; forms that could be unformed. Deleuze's fold was also associated with mystery and the female sex organ. Though he wrote at length about the fold, he never discussed folding his own laundry.

In fact, he hated handling cloth of any kind, citing his unusually sensitive fingertips as one reason for his strangely long fingernails. "I haven't got the normal protective whorls, so that touching anything, especially fabric, causes such irritation that I need long nails to protect them." More to the point, such questions were traditionally considered outside the scope of European thought, in the sense that they belonged to the domestic realm. The bourgeois public sphere wasn't a place for laundry, it was a place for ideas and discourse, and Deleuze resisted any discussion of his autobiography or private life.

With the rise of social media, images and information relating to the private life of the home and family are considered fodder for publication, now called "sharing." At the same time, domestic space and domestic labor are made available for public consumption via the "sharing economy." Online platforms have embedded themselves in the private sphere, troubling its boundaries.

Though it may sound worrying, this confusion of public and private has its benefits. The realm of discourse and ideas can no longer insulate itself from housework and the embodied knowledge of those who perform it.

**

Despite its physical and emotional demands, folding is often relegated to the underpaid and the unpaid. When I lived in Williamsburg, I would often use the drop off service at the local wash and fold. One day, the owner (a chatty, old-school Brooklynite) started complaining about how hard it was to find good "help" to keep the service running. "They get worn out," he said, and he wasn't talking about my underwear, but about the women who folded it. It was unclear whether the source of the exhaustion was the physical aspect of the labor, or the emotional burden of caring for so many strangers' garments.

Sadie Plant famously argued that the material of digital culture is textile. If this is the case, the work of "folding" our digital material–keeping it tidy and organized and presentable–is largely, and perhaps unwisely, entrusted to platforms, where our folders can now be found.

Most of the folding is automated, performed by complex technical ensembles that are largely controlled by men. When it does need to be performed by hand, as with the policing of content, it is still performed by underpaid and invisible labor forces.

In the age of the cloud and Spotlight and seemingly endless storage, I've gotten worse at backing up, deleting unwanted files, and organizing the ones that remain. My Downloads folder begins to resemble my sock drawer. I seem to be only too eager to depend on platforms to do my folding for me.

**

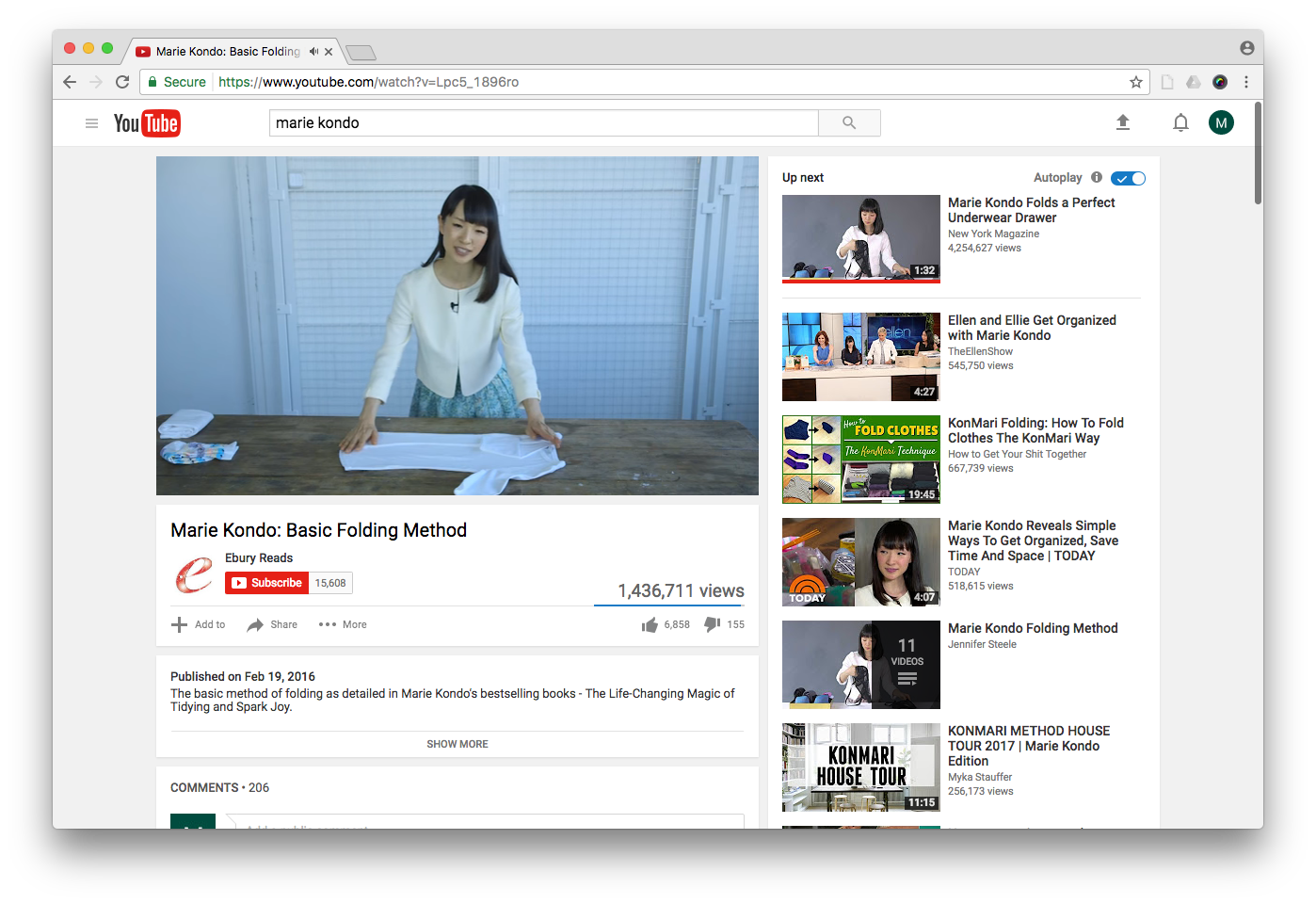

"Many people think first, which one should i get rid of? But it is much more important to think, which one to keep."

In an on-campus talk at Google, Japanese tidying guru Marie Kondo described a careful and intentional approach to discarding unwanted objects as a way to a more joyful life. She argues that one should be able to see every garment in a drawer immediately upon opening it, with each item folded to stand at attention, ready to be re-performed.

When making the decision about what to let go, Kondo emphasizes the importance of understanding one's embodied relationship to any item. "Make sure you touch it… Imagine how your body reacts to that moment, how you feel when you touch the item."

In a digital context, this kind of embodied relationship could be a way of escaping the pitfalls of understanding digital culture as if it revolves around a "disembodied image, re-created in the virtual spaces of sign-exchange and phantasmatic projection." Carol Armstrong called this the "cyberspace model" of understanding digital culture in her response to October's "Visual Culture Survey" from the Summer 1996 issue. She posited a binary division between, on the one hand, a new media criticism that focuses on "'exchanges circulating in some great, boundless, and often curiously ahistorical economy of images, subjects, and other representations," and, on the other, a critique that takes into account the materiality of objects:

The material dimension of the object is, in my view, at least potentially a site of resistance and recalcitrance, of the irreducibly particular, and of the subversively strange and pleasurable. It is, again at least potentially, a pocket of occlusion within the smooth functioning of systems of domination, including the market, hierarchical thought-structures, and subject-positionalities: a glitch in the great world wide web of images and representations.

In her broadside against the cyberspace model of criticism, Armstrong was perhaps guilty of insinuating that new media lacks materiality, that this kind of material difference can only be found in the "painterly, sculptural, photographic, filmic, what have you" - not the digital.

By folding the web, we can find an embodied knowledge of its material differences, its pockets of occlusion. But this cannot be found in the type of folding that GentleWhispering presents. Although her video is intended to activate an embodied response, she describes it as a role-play, failing to acknowledge that role-playing also has consequences, or that materialism goes further than the body.

Kondo's advice, in contrast, could be understood as a way of avoiding the pitfalls of the cyberspace model. As users, we should learn to touch our digital materials, to activate our embodied knowledge of our digital archives, to feel our way across their material, historical threads, and perhaps to let go of what we cannot keep. And this is hands-on work, even if the immediate surface under our fingertips is only liquid crystals under glass or the plastic of a keyboard.

With thanks to Eva Díaz, Kaela Noel, Dillon Petito, Sylvia Gutierrez, and Tatiana Turin.