The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

A number of your works focus on how "relevance" as a cognitive concept is generated or understood; your non-linear social media site, deli near info, for example, reflects on how temporality affects relevance in the stacked perceptual field of social media streams. Could you talk about how you understand relevance, and the ways in which you feel digital culture reveals how our minds work and/or creates new modalities of relevance?

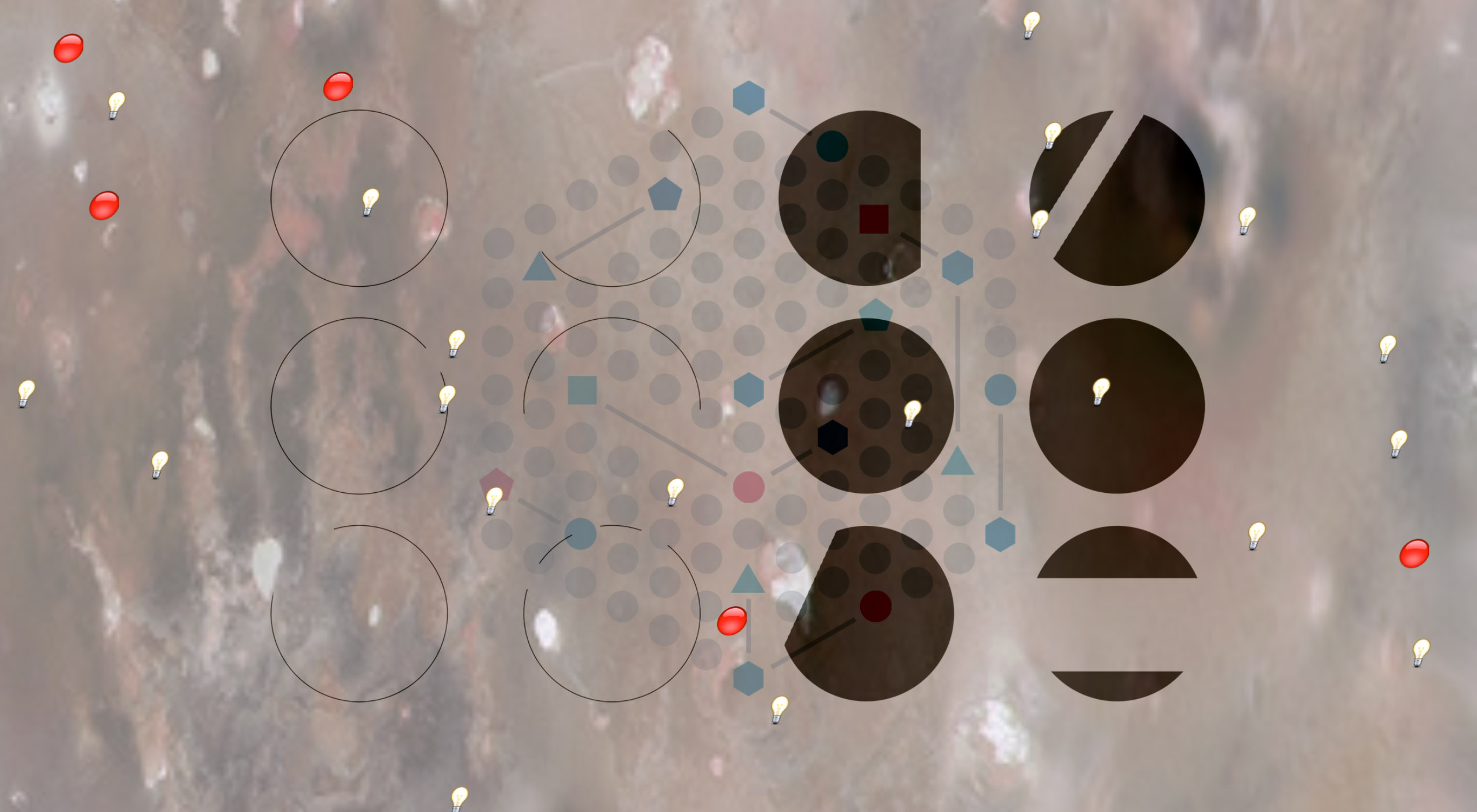

We talk about the internet as if it’s this revolutionary thing, but it’s primarily based on written language. And everything that you can find is done by using words. Say you have Image A and Image B and you want to find some kind of connection, first, you will have to come to some sort of conclusion about what that image is about and then you describe it with keywords, and a match is made based on those interpretations which is very likely to be a connection on the most common denominators like color, or media, or age, but not about other intrinsic, more difficult things to articulate like a particular uncanniness or a particular aesthetic, but that kind of information would disappear because the relation has to be translated into words. So what I tried to do with the deli near info was to take away the written language proxy and have the images directly connected. Often people say that if you can’t articulate it in language, it doesn’t count, it’s nonexistent; but, still, I think it is possible to make these inarticulable connections. Systems help you to structure your brain so that over the longer term, things are emerging, that’s why it’s important that older things are as valued equally to new things. It's a bit like psychoanalysis, in a sense. Also with older ideas if you think about, say, printed matter in that case you have to think an idea through completely and give it a form and then publish it, and it is unchangeable. So you’d better figure it all out properly before you have it printed. But that’s not the case anymore; now, it’s a continuous process. Before, if you printed a book and you read it and then a few weeks later said "Oh, shit, I was wrong"—like you’ve made a mistake either conceptually or you have typos—then you have failed in a way; but if you make an app, then these events are not seen as a failure, they’re an "improvement." If an app is not receiving updates then it’s actually a dead product. Nobody is going to complain if they update Facebook and say, "Hey Facebook, I thought you had it right the previous time"—this is essential. The internet is an ecosystem of live objects that interact.

Harm van den Dorpel, deli near info (screenshot, 2016)

You have spoken about how your work often seeks to approach information processing from a sidelong angle—not seeking out the most obvious, efficient connection but a connection that is relevant in another way, or which eventually becomes relevant in a surprising way. Given your own background in artificial intelligence (AI) development, has this approach to working with technology given you any perspective on the ways in which the "smartness" of smart devices mirrors or diverges from human intelligence? In many of your works, you seem to be making the case that smartness and intelligence must be understood as distinct concepts, and that the "randomness"—or apparent randomness—of certain associations is perhaps critical in delineating this distinction: smartness works to filter out randomness, but intelligence assimilates or contextualizes it. Is that an interpretation that resonates with your own understanding of your practice?

There is one approach to art making, or thinking, where you have a bigger plan and you work toward a particular goal; you kind of already know where you’re heading in advance, and what you’re going to say. This is a legitimate way of working, but I find, in creating, that if I work that way, then the outcome is not going to be desirable because a lot of what I do relates to the emergence of things. I’m not esoteric, but I feel that there are things going on in your brain—there’s a lot of noise there, but there are also a lot of ideas and interests already percolating which you haven’t been able to formulate fully yet. When you have an information system in which you put all those raw fragments and you give it a lot of small feedback on each fragment, the system might generate random connections and you can make judgements based on those so that, gradually, the randomness aligns into something that maybe has more substance. This conclusion is not something I could write down, but it’s the whole point. Consequently, it is getting away from the dominating force of written language—which I love as well, but it’s also possible to think visually or associatively or intuitively.

Harm van den Dorpel, deli near info (screenshot, 2016)

Your recent exhibition at Neumeister Bar-Am, "Ambiguity points to the mystery of all revealing," featured a number of works that reference the biological world, not least the large work, Chrysalis. As digital aesthetics are encroaching into all areas of life, do you see them as influencing the expectations for biological outcomes? One could draw a parallel with dog breeding which itself could be thought of as an application of the same logic as contemporary versions of bioengineering: information manipulation in the service of specific biological outcomes, often outcomes seeking an aesthetic result. Do you feel that there are unique ways that digital culture and aesthetics are influencing this process, or is it merely the continuation of the pursuit of aesthetic pleasure/cuteness by other means?

It’s a difficult question. I can start by saying a few words about that show which touched on the idea of incompleteness and change over time, also of things that are essentially dead and which lack the capacity to transform. The cocoons were made with heat-shrink foil, which is one of the cheapest materials there is, and it doesn’t last. The inside of the cocoons is bubble wrap, so it’s really like packaging foil that’s usually discarded, but the chrysalis is this big metaphor for transition; at the same time, however, the ones in the show are never going to pop; they’re never going to "happen," so the objects are dead in that sense. Then the other works in the show were white boards which were also incomplete but which were asking for interaction—but it was unclear what people should actually contribute to them. Both works were about this change and incompleteness and were sort of opposites of each other. The show was, in part, about dissatisfaction with the staticness of art production— but not just art production, also any particular theory or religious idea, any kind of dogma. Any kind of thing we fix is immediately dead. Every kind of conclusion for me is a problem.

Harm van den Dorpel, "Just-in-Time," installation view at American Medium (2015)

In other interviews you have frequently been asked about your statement that "net art is dead." Though perhaps too much is made of a single aphorism, one of the things that those conversations addressed is the approach you took earlier in your career in which you sought to build the platforms, sites and other digital objects you created more or less from scratch. You speak of the ease of accessibility in changing the dynamics and expectations of digital creation. While, no doubt, no end of second-tier net art is now being produced, do you feel that there is, in this process, a dialogue with the conceptual turn in non-digital visual art over the last half century wherein the "object" that results is secondary to either the idea from which the work derived or the artistic process by which the work evolved into its present state? If that is the case, is that turn necessarily a negative, or does it merely shift what "net art" is about?

I recently found out that I am still extremely inspired by the actual technical possibilities of networks and making works for computers—basic computers. There was always the promise that this was going to happen, but if you look at the art online, art that is often branded as "digital art" or "internet art, it’s actually old media. It’s video, or collage, or text, or music—which are all amazing and good, but I still believe that you can make art by taking advantage of medium specific properties of technology. That’s why I have Left Gallery now. The whole idea of post-internet art is you go back to the media we already had and say "now we’re going to make art about the things you can do on the internet," which is fine, but the problem, I feel, is that if you’re going back to sculpture making or collage making, I don’t have much to contribute anymore. I feel that in the field of internet art, pure internet art, there’s still so much to discover there, from a pragmatic point of view, my aesthetic language is stronger when I do online stuff. I tried to deny this, but I just have to admit it. In terms of craftsmanship, I’m genuinely strong there. I also studied it, and I hate buying materials.

Harm van den Dorpel, Scrum Kanban whiteboards (2015; courtesy of Neumeister Bar-am and American Medium)

You have spoken about your recent work as addressing the mechanics of curation. The term "curation" is ubiquitous these days—people curate playlists, desktops, "evenings," menus—but perhaps the most useful interpretation of the term in relation to your work is again to be found in the notion of the management of information flows. Could you speak about the ways you understand and apply the term "curation" in your work, and how you seek to explore it via digital and IRL methodologies? Is it perhaps connected to the way you seek connections in supposedly unrelated objects? Is the mind itself, and the programs designed by the mind, something you understand as a framing device?

The word "curating" in Dutch means when a company goes bankrupt and the stakeholders want their money back then someone must execute the "curation" and determine what kind of value is in the remaining stuff and then sell it. The proceeds then go to the people who have lost out on the investment. That is the intuitive connection I’ve always had with curating. I used to have Club Internet in 2008, and I think curating for me means I see things that are good, or interesting, or maybe are better than I could ever do, but they’re not getting attention, or they’re not understood because they’re not surrounded by other objects that make it clear what they’re about. That’s why I want to curate, and not just work by other people, but things I encounter in the world, or things I upload onto deli near info where I think, “these two things are interesting, but I don’t really know why, but maybe let’s just put them there and wait for a bit, then maybe add something later and see what happens.”

Initially my curatorial perspective starts out very open, but there is no interest in just leaving things open and never reaching any kind of conclusion, so there is an ideal, or a hope, or a desire, that gradually, if I add more and get more information, that something will come out of it, and not just the number 42 [laughs], but something which I would really love. Let’s take Facebook; Facebook knows a lot about me, and it could, maybe, actually tell me things about myself which I haven’t figured out yet, but they’re not in the business of doing that. There’s also a political dimension to my understanding of curation. I don’t agree with the ways information is treated. deli near info is tiny, and its user interface awkward, but still I really hope that there will be some kind of change that will result from it to begin to create a situation where information control is given back to the people. Maybe it sounds a bit hippy, but actually I really want that.

Harm van den Dorpel, Left Gallery (screenshot, 2016)

Questionnaire:

Age:

35

Location:

Berlin, Germany

How/When did you begin working creatively with technology:

That question could mean so many things.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

Studied AI at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and Time Based Arts at the Rietveld Academy, also in Amsterdam.

What do you do for a living, or what jobs have you held previously?

I'm an artist, software developer and have worked in art education. In that order.

What does your desktop or workspace look like (screenshots or pics please!):

I often wonder what people expect to find in my studio.

Harm van den Dorpel, Transplant (deli near PAN franchise) (2015)

Top image: Harm van den Dorpel, deli near info (screenshot, 2016)