This essay accompanies Eduardo Kac's 1985 work Reabracadabra as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

-

In 1985, Brazil was following Europe and North America in their adoption of videotex information systems—a precursor to the web—of which France's Minitel was the most widely adopted and known. This new platform attracted a group of pioneering Brazilian video and telecommunications artists, excited by both the possibilities and parameters of the system, and the potential of using it to create new kinds of public space.

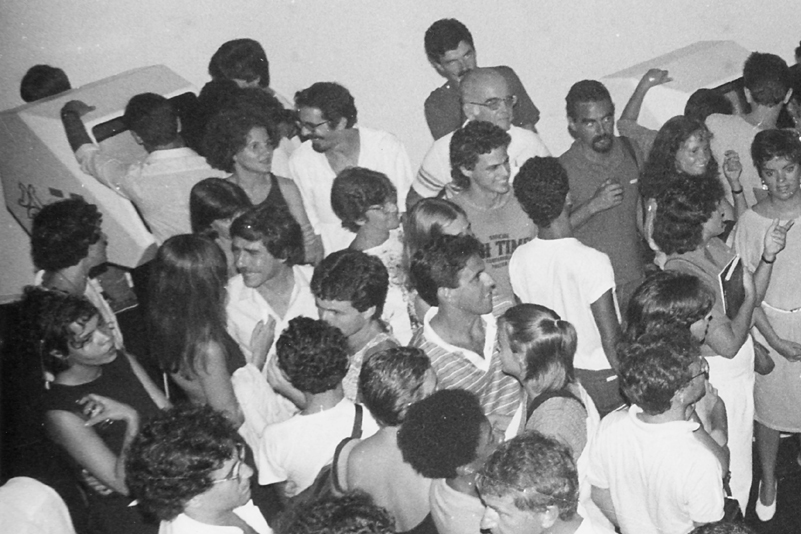

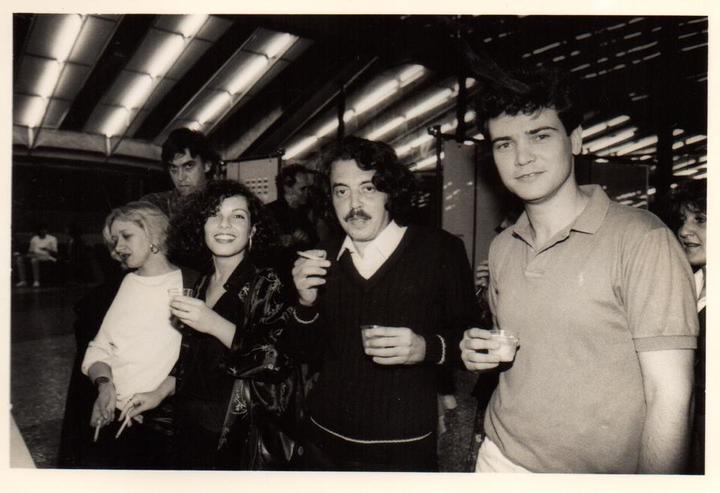

Opening of the “Brasil High-Tech” exhibition, organized by Kac and Flavio Ferraz, at Galeria de Arte Centro Empresarial Rio, Rio de Janeiro, 1986. Two public Minitel terminals are seen in the back. Photographer unknown.

Brazil in 1985 was changing—beginning to emerge from a twenty-one year struggle to restore democracy from a repressive military dictatorship that spread instability, betrayal, and despair throughout a country already subject to chronic inequality and poverty. During the military government period, Brazil was run almost exclusively in line with the interests of its white elite. In 1974, ten years after the 1964 coup d'état, an economist called Edmar Bacha coined the name “Belíndia” to describe his country's socio-economic reality: a small, wealthy Belgium surrounded by a massive and destitute India.

While thousands of artists, writers, musicians, trade union leaders and student organizers were forced into exile by the military government, many in the struggle who remained were imprisoned and tortured (including recently deposed President Dilma Rousseff). After a campaign of massive street demonstrations called Direitas Já! (Direct Elections Now!) in 1985 Brazil elected (albeit indirectly) the first non-military president since 1964, Tancredo Neves, only for him to die hours before taking office, and be substituted by another former dictatorship figure, José Sarney.

Artist Eduardo Kac recalls:

The military dictatorship was suppressing freedom of speech and eliminating public space; it also tortured and killed its own citizens. At the same time, however, this government had collapsed economically; globalization was taking its initial steps, and the protectionist model of the military dictatorship was no longer useful. So the country was moving towards a transition, but it was still under a clear military rule. It remained an environment where the primary idea of the body was that of the tortured body, of the distorted body, of the suffering body. In this context, I saw the opportunity as citizen and as an artist to create public space where there wasn’t one. [1]

Against this uncertain backdrop, the mid-1980s also saw a surge in availability and demand for new technologies in Brazil, with some urban centers reaching relative parity with Europe in terms of access. Trade restrictions prohibited the sale of computers from overseas manufacturers, spurring a range of affordable, locally produced clone systems to appear. A Brazilian company called Unitron, which had previously sold machines based on the Apple II, even developed a Macintosh clone. Ultimately, under pressure from the US government, and with a local media campaign conducted by Apple warning of a “trade war” between the countries, the project failed. The legal repercussions affected Apple's operations in Brazil for decades.

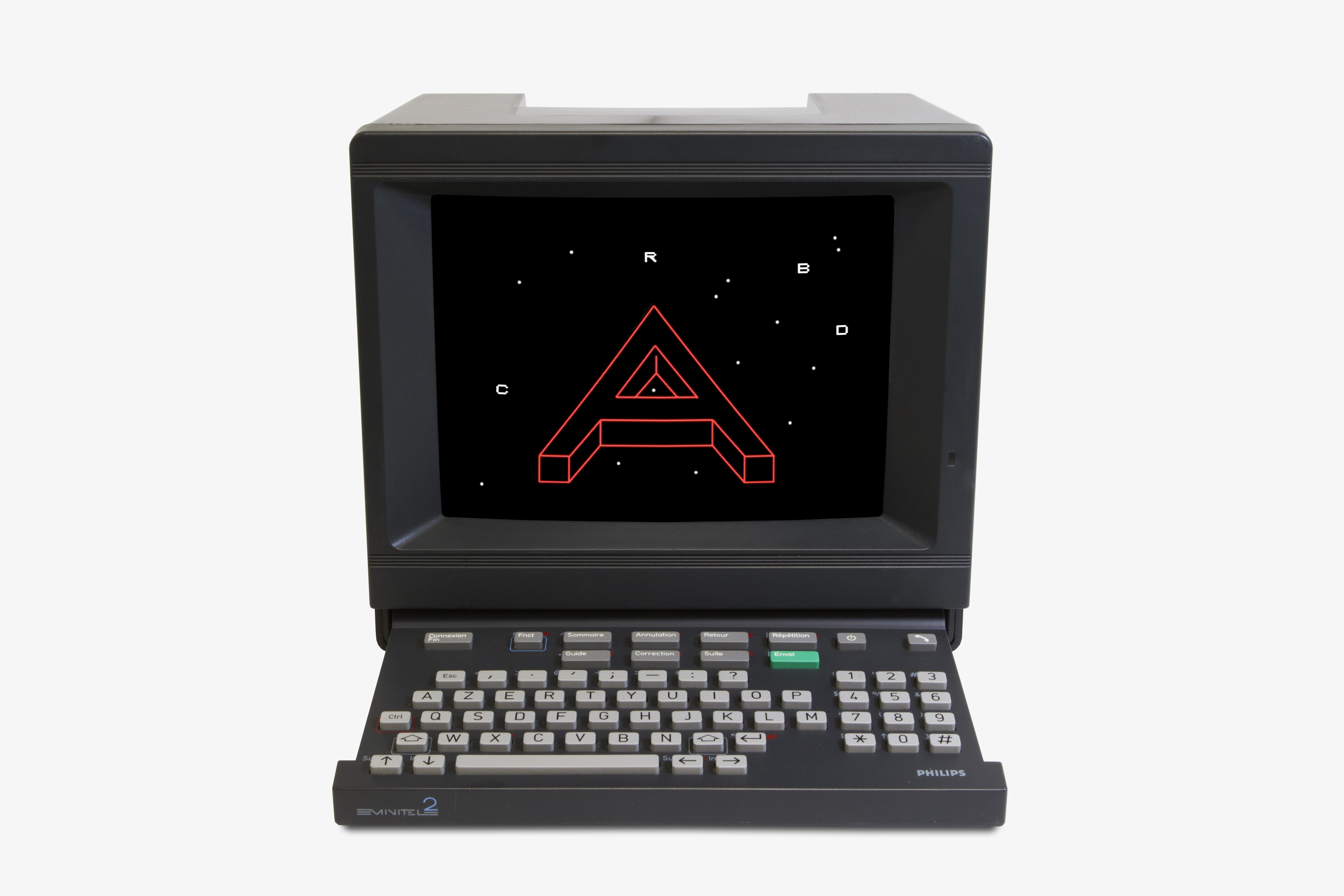

One of the technologies which did succeed was a Brazilian variant of the French Minitel system, in which a remote terminal was used to access pages interactively through fixed phone lines. It was a precursor to today's internet and functioned similarly, with “sites” containing information on a range of subjects, and features such as home banking and home shopping. It also also featured a messaging facility analogous to email.

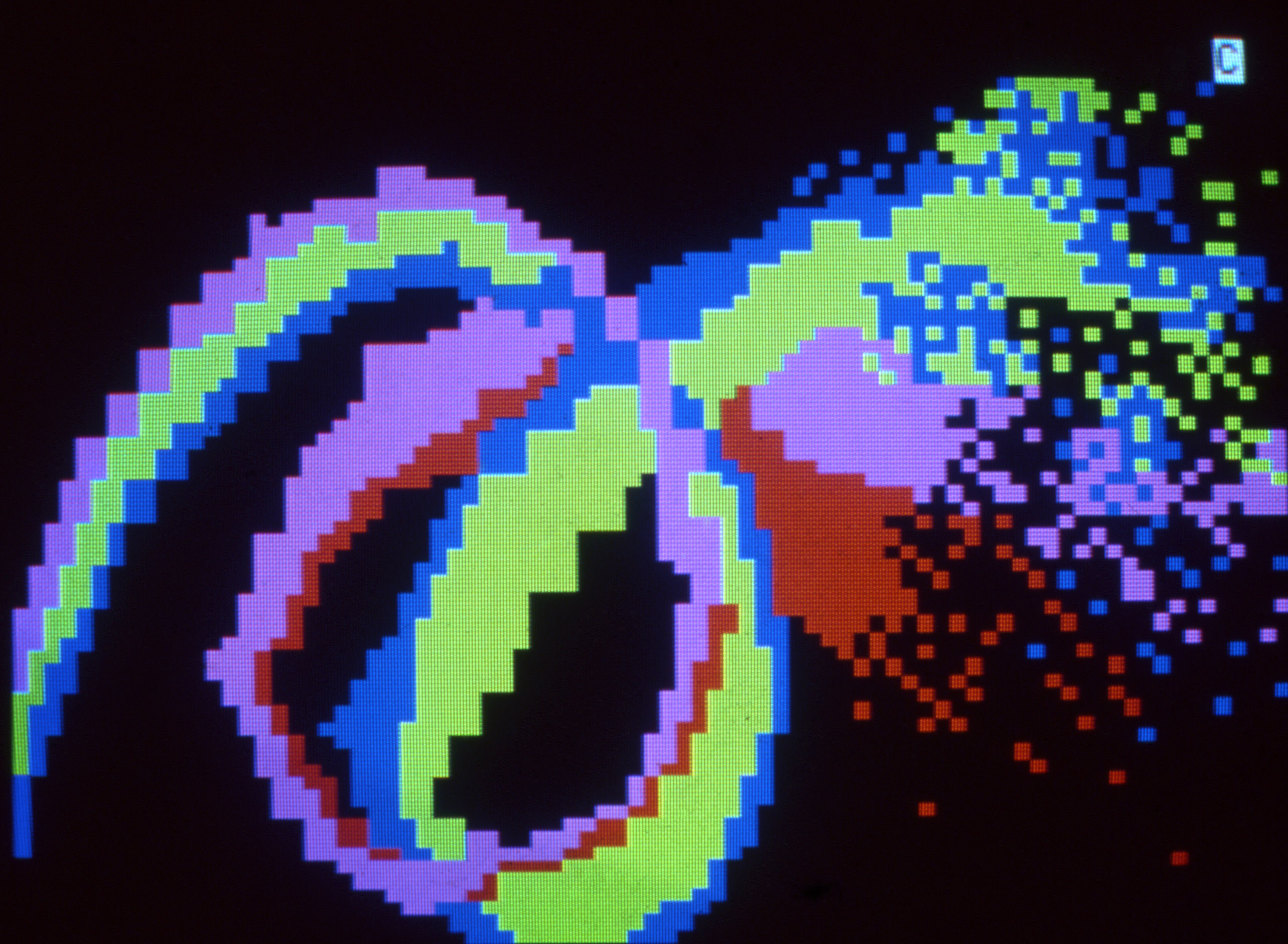

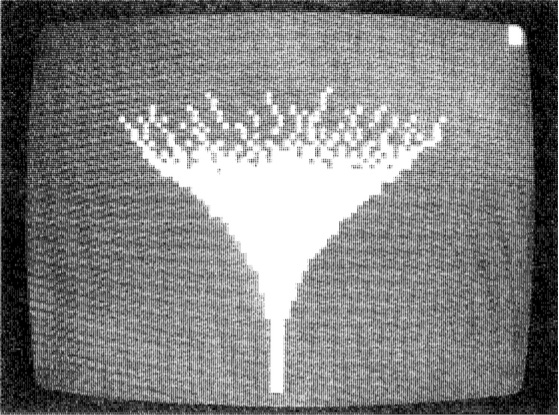

Eduardo Kac, Reabracadabra (1985). Videotexto artwork shown on Minitel terminal.

Kac:

The Minitel network was a very different environment compared to the current internet. One thing that stands out for me is the fact that the pixel which we take for granted as this little square, this indivisible unit—the pixel in the Minitel system was divided into six parts, and it was vertical. A very strange creature, because the Minitel system was a hybrid of ASCII and some proprietary system from France Telecom. It was unique. In France it became very popular for a number of years, France was then on the cutting edge of digital networking.

This has to do with the fact that in France anyone who wanted a terminal could go to the post office and take one home for free. And because the unit was free and you already had a telephone at home, the thing took off, and you had millions of people online, doing everything we do online around 1982 to 1985. But a few years ago the Minitel network had its final cable unplugged, and the Minitel network is no more. This is interesting because it is also cultural— it is perfectly conceivable that the internet as we know it now will someday also cease to exist.

Countries such as the UK, France, Japan, Canada, USA, and Brazil implemented different versions of the videotex concept under their own names: the UK created the first system in operation called Viewdata (changed to Prestel), France had Teletel and later Minitel, in Canada it was known as Telidon, in Japan it was Captains, and in the USA the network was named Videotex.

.jpg)

In France, Minitel was not only a technological advance but a political initiative. In the French view, countries without massive natural resources needed to develop and export their own new computer technologies; government action was needed to promote a transition to the “telematic” future. There was also study and debate about what positive & negative effects videotex might have on society. Minitel's continuing popularity into the late 1990s actually became a barrier to internet adoption in France.[2]

The Brazilians bought the rights to France Telecom's Teletel system and branded it Videotexto. Launched by the state of São Paulo’s telephone company Telesp (Telecomunicações de São Paulo, later Telefônica), it operated from 1982 until the mid-nineties. Several other Brazilian state telephone companies followed suit with similar videotex offerings, but each state retained their own standalone databases and services. The key to its success was that the phone company offered only the service and phone subscriber databases, while third parties such as banks and newspapers provided the valuable content and services. The Brazilian videotex system's popularity peaked at around 70,000 subscribers in 1995, just as the internet arrived.[3]

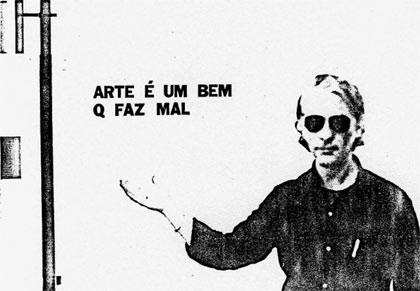

São Paulo, the largest city in the southern hemisphere, was home to rich and diverse cultural movements, and at this time in particular a robust post-punk scene. It didn't take long for visual and video artists to see the potential of these new popular platforms. One of the enthusiastic adopters was Julio Plaza, a Madrid-born artist, writer, and professor, who first came to Brazil in 1967 as part of the Spanish contingent for the 9th São Paulo Biennial that took place the following year, and who went on to emigrate to Brazil permanently six years later. Enthusiastic about Minitel and Videotexto, Plaza’s curating fostered a new circuit for digital art. His exhibitions “Arte pela Telefone: Videotexto” (1982) and “Clones,” both at MIS (Museum of Image & Sound), combined videotex with television and radio. Meanwhile, Unibanco and Telesp promoted a videotex graphic design event at MASP (São Paulo Museum of Art) with their in-house designers Rodolfo Cittadino, Rosemari Cristina Zangirolami, and Verginio Zaniboni Netto.

Art is a good that does evil, Julio Plaza (1982). Xerox on paper.

In 1983, at the 17th São Paulo Biennial, curator Walter Zanini invited Plaza to curate a multimedia section, which was titled "Arte e Videotexto." The excitement for these new platforms and media was evident in Plaza’s essay published in the 17th Biennial catalogue:

The alliance of audiovisual media, telecommunications, and information technology brings new possibilities of communication and expression. Technological progress is much faster than our ability to assimilate and use these new media.

Videotex, unlike other means of mass communication, is interactive because it is born of an interpersonal environment: the telephone. As for the other means are strongly centralising information. With this interactive character, the videotex is characterised as a dialogical vehicle because it breaks with the unidirectionality of the communication world, which seems to mean the beginning of the end of mass society (taking the word in the sense of communication mediated through unidirectional transmission systems), as same in which the user can interfere with and create information, making them virtually an editor. The teletext features are, thus, a democratic vehicle, since the bi-directionality allows the expression and the return of information, breaching the principle of causality, unidirectionality, and authoritarian characteristic of the mass media. With videotex, you can not "educate" the masses.

Videotex thus offers the possibility for the participation in social and community life of individuals, taking a step forward in the democratisation of the information process.

This trend was already taking shape from the 60s, with the socialisation of the means of reproduction and production of reprographic systems (offset, xerox, among others), which facilitated, since then, the ability to copy entire issues, putting into question the notions of copyright and, above all, the copy-copyright. Furthermore, these same procedures enabled thousands of authors and alternative magazines in the 70s.

This democratisation and socialisation of the means of reproduction and production gives us the potential for the formation of electronic editorials at low cost (Comparing to the newspaper, for example) production, publishing small groups or users based on the principles of spontaneous and informational affinity, at the same time it involves the user's consciousness in choosing and interacting with the information.[4]

Plaza developed these ideas in conversation with his students at Centro de Artes Visuais Aster, the art school he co-founded with Zanini and artist Regina Silveira. “Julio invited many artists from several generations,” Silveira recounts. “Many of the artists involved were very young and went on to be major artists, they were the next generation, and they had been our students.”

.jpg)

Regina Silveira´s printmaking class at Aster. Photo courtesy of Ana Maria Tavares.

The works in the exhibition were presented in the main biennial building on a number of Videotexto monitors. Works by videotex artists from Canada, made using the Telidon system, were also on display. Aster students who participated in the exhibition remember the sense of strangeness and excitement surrounding the project.

Alex Flemming:

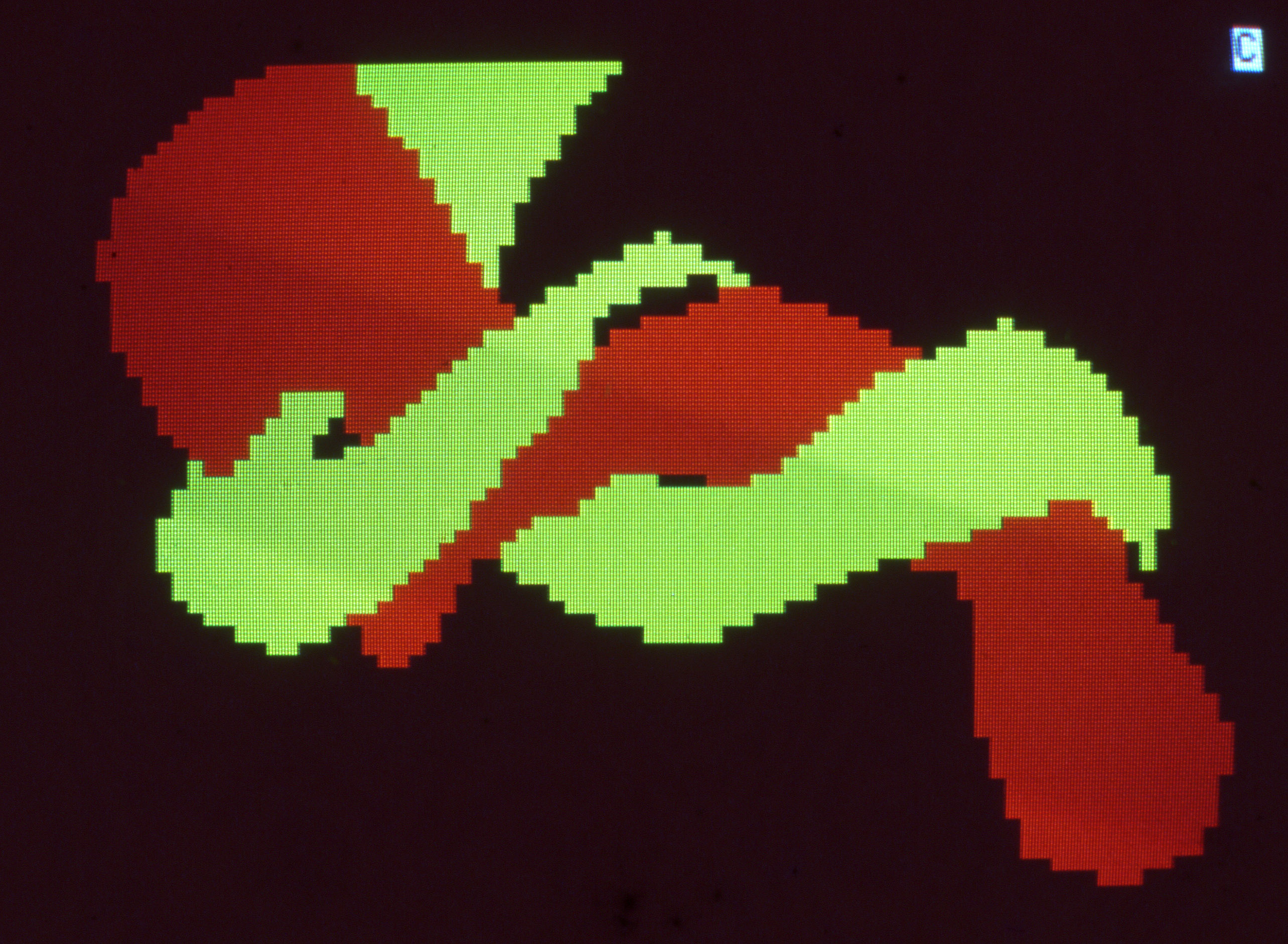

I made a female vagina that transformed itself into a glass of champagne. I think I made it like this old children’s game—battleship. I had several pieces of graph paper, and I made the image with those square dots, and I say this this and this goes to there… Prior to this I studied cinema and there was lots to do with animation for sure. There were several TV sets and people could go there and press a button and the Videotexto work would begin to play.

Work by Alex Flemming from "Arte e Videotexto." Copy of photograph by Leonardo Crescenti Neto.

Ana Maria Tavares:

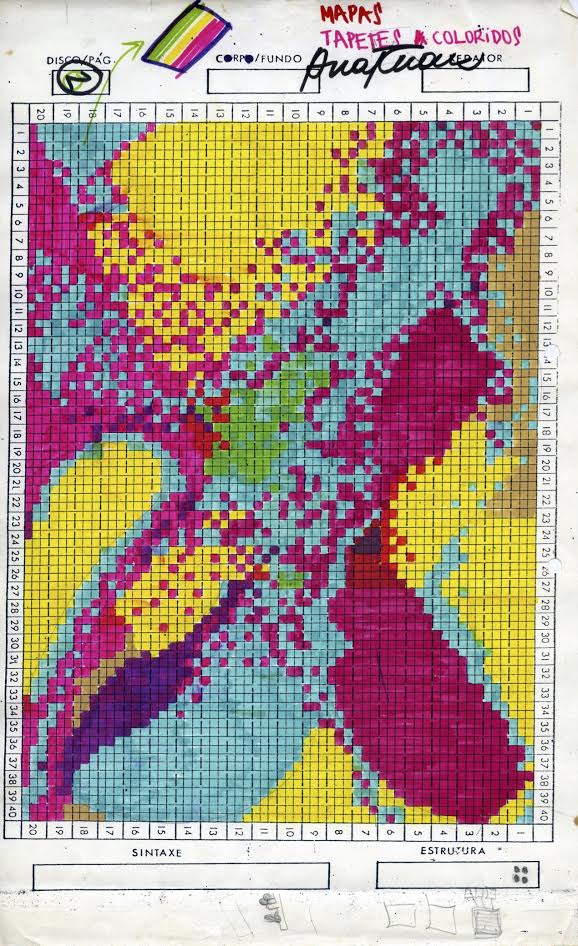

It was strange and exciting, there were these little monitors, not even monitors compared to computers now, they looked like The Flintstones in comparison, but it was really fun to have the work and have this translated into different media.

Photograph of work by Ana Maria Tavares from "Arte e Videotexto."

An example of Ana Maria Tavares's grid map for her Videotexto works.

Fellow Aster student Ana Aly, whose focus was visual poems, was also invited to participate. She was part of a separate group around the artist Philadelpho Menezes. She recalls:

At the biennial I watched the public with excitement. I thought everyone reacted positively and saw us as innovators, and that our group would be admired, seen as courageous, even as a model! That was how I saw the exhibition at the time. It was not exactly like my piece in Videotexto but my visual poem "City" also alluded to technology—small windows representing the old punch memory cards of computers.

I Mostra Internacional de Poesia Visual de São Paulo, 1988. L to R: Rozélia Medeiros, Ana Aly, Villari Herman, and Philadelpho Menezes

Silveira’s piece at the Biennial exhibition was a digital adaptation of her 1977 piece Pudim Arte Brasileira (Brazilian Art Pudding). In the form of a recipe, it was an ironic, acidic commentary on the false ideology and market focus of Brazilian contemporary art at that time. In the 1970s, she had distributed the piece to the public as a sheet of paper stationed next to the escalators down to the São Paulo subway network. Silveira remembers that the low-resolution quality of Videotexto gave the work a very different feel from the Xerox version, almost like a weaving:

You have seen in the catalogues how the resolution was, it was... very difficult to plan precise images because the mesh, the pixels were very big, a kind of basket pattern, very open. And the pieces were like that, so every artist sent their project to Julio and he and a group of technicians executed them. At that time Videotexto’s rights were controlled by Telesp, the state company of telephones, so it was a nice connection to have this group of artists making projects for Videotexto.

Two versions of Regina Silveira's Pudim Arte Brasileira, 1977 and 1983.

Videotexto offered a perfect focal point for many of the artistic currents of the moment, as Tavares recalls.

Conceptual art was very important in Brazil, and it coincides with dictatorship. I think that technological art in Brazil is different and strong because of the way that artists had to move around... the idea that artists have to propose things, put up exhibitions, curate shows, and move around the city was quite important.

Everybody was really interested in Xerox, doing works with Xerox, photomontages, microfiches, and Julio Plaza was very much interested in videotex and other kinds of technology structures. We were all his students, we were very young—twenty-two, twenty-three—and he invited amazing artists but also very young artists, and it was really very exciting to join with them and have all these discussions about Videotexto.

.jpg)

With the excitement surrounding Videotexto at the 1983 biennial, service providers Telesp and Telefônica perhaps saw the potential in working with artists to raise awareness of their new system. Livraria Nobel bookstore inaugurated a permanent gallery for Videotexto Art, called “Arte On-line,” which was available in the store and across the Brazilian Videotexto network.

One of the featured artists was Eduardo Kac, whose 1985 work Reabracadabra, an animated Videotexto poem, was part of the exhibition. Kac had been active in the new media art scene since 1981, and having previously experimented with Xerox emerged from this group of pioneers in telecommunications art during that pre-web period.

Kac, reached recently by Skype, explained that

Reabracadabra explored the idea of non-locality, the question: "where is this work?" It's on a remote server, nobody knew exactly where it was. Location was completely irrelevant to the experience. Of course today this is an ordinary fact, but back in 1985 it was an entirely new frontier.

Artists in Brazil continued to see potential in Videotexto art, and in 1986 Telefônica and a dozen or so other companies sponsored another exhibition, “Brazil High-Tech,” curated by Eduardo Kac and Flavio Ferraz.

In one of Brazil's biggest newspapers, Folha de São Paulo, Eduardo Kac previewed the exhibition in the form of a manifesto:

Today, when the rigidity of Renaissance painting seems to announce its return to the world of art, either explicitly, or camouflaged through informal abstraction or expressionism, there are artists who challenge the art market with their incomprehensible works manifesting a techno-aesthetic revolution, and projecting the art of the 21st century.

In a telematic revolution, the large influx of children into the “Brazil High-Tech” exhibition is not in vain. While some adults are still trying to remain oblivious to technocultural reality, children will grow up eating processed fruit under the artificial light of monitors, indulging their fantasies and emotions in this holomatic adventure, fundamental for the construction of a new world: politically fair, economically free, and socially human.[5]

Videotex played a powerful symbolic role in a moment when, amidst a repressive totalitarian regime, real cultural and political change suddenly seemed within reach. Even though the network itself did not survive, it is itself poetic that a unique telematic vision for new forms of democratization through art emerged in a city like São Paulo, where a centuries-old struggle for public space and the public domain plays out through a maze of walls and fences, now criss-crossed by the cables that underpin our new technocultural reality.

Additional reporting by Adriana Galuppo and Michael Connor.

Notes:

1. "Trans-Genesis: An Interview with Eduardo Kac Lisa Lynch." Originally published in New Formations, No. 49, Spring 2003, London, pp. 75-90. Accessed at http://www.ekac.org/newformations.html

2. Robert N. Mayer, "The Growth Of The French Videotex System And Its Implications."

3. Verginio Zaniboni Netto, Videotexto no Brasil, São Paulo: Livraria Nobel S.A., 1986.

4. 17a Bienal de São Paulo, Catálogo Geral, 1983.

5. Eduardo Kac, “'Brasil High Tech', o cheque ao pós-modernismo," Folha de São Paulo, Informática, April 16, 1986

All interviews conducted by phone or Skype in 2016 unless otherwise noted.