“Imagine if we could begin our little life all over again. Imagine if it was all nothing more than some electronic game. Imagine if I knew then what I know now.” —Deus Ex Machina, Automata, 1984

If videogames can be said to possess an “official history,” it is predicated primarily on the advancement of technology, the shifting of markets, and the consolidation of multinational corporations. This is a history which prioritizes technological advancement, from computer gaming’s rise as the product of quiet dissent among the engineers of military computers at MIT (Spacewar!, created by MIT engineers in 1962, is often regarded as the first iconic computer game),1 to the clinking of arcade machines and the ensuing success of the home console, which allowed publishers to cut out the middleman and sell their products directly to consumers. The changes that followed—developments like Jerry Lawson’s brilliant removable cartridges, which allowed games to be sold separately and individually from the consoles that ran them (prior to this, games were hard-coded into consoles and cabinets), and the less-brilliant Bit Wars, marked by petty marketing and consumer battles over the relative processing power of competing consoles—are understood through the lens of tech-progressivism.

All of this foregrounds the growth of multimillion dollar franchises and legacy IPs owned more or less exclusively by a corporate oligopoly with an iron grip on both the culture and the market. The videogame industry has eagerly adopted the narrative of building a better machine and of selling a better product. The very argument of “games vs. art,” which was for a brief period stoked by Roger Ebert’s claims that “games can never be art,” has always been a sham that was willed into existence and accepted as fact by critics, academics, industrialists, and gamers themselves. But we should call this what it is: it’s not a struggle between “art” and “games,” it’s a struggle between “art” and “commerce.”

There is a lesser-known history of the games themselves. By this I mean a more intimate account composed of a long heritage of games deliberately concerned with the artistic, political and personal. For these, the term “artgame”2 comes in handy. This term refers to videogames intended to provoke artistic ideas but still be understood contextually as games. The “artgame” stands in important contrast to “game art,” which is usually produced by conceptual artists and aims to treat games not as a form unto themselves but as raw material for new works. The line between the two, however, can and does blur. It’s sometimes unclear whether or not a given piece of digital art is intended to be read as a “game” or as “game-based conceptual art,” and I would argue that as games and art converge to insist on an unassailable distinction between the two is to engage in futile pedantry.

Videogames as a medium and culture have more or less grown up on the internet, which hindered the growth of the art form as much as it helped it. On the one hand, the internet did facilitate the proliferation of small, independent and personal gaming experiments by allowing people to make and share them for little to no money. On the other, the growth of the corporate web has meant that a great deal of gaming’s art history has been lost, hamfistedly revised, or put into the “weird” corner of the medium’s past mistakes.

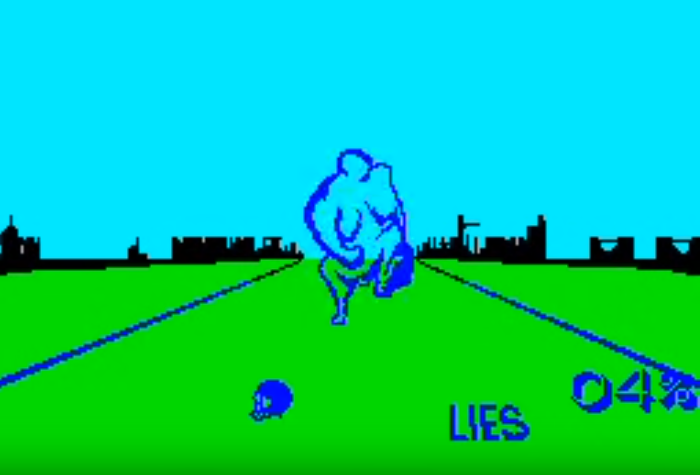

Still frame from Deus Ex Machina (Automata, 1984).

The very early days of the Bulletin-Board System were teeming with independent game creations to be shared, downloaded, and played by in-the-know enthusiasts, and folkish online communities centered around small, experimental works persist to this day. The maturation of games as a medium via the internet has spelled a more palpable opportunity for the growth of democratic, global, interdisciplinary, multimedia movements and collectives. The dark side of all this is that as the internet has evolved it has become more deeply corporatized, and market segmentation benefits from the fact that the nerd identity—which, as Kom Kunyosying and Carter Soles point out in their piece, “Postmodern geekdom as simulated ethnicity,” was effectively invented by corporations—has been elevated to an almost political imperative.

Decades prior to the advent of the internet, a great deal of 20th-century art was preoccupied with more “interactive,” participatory approaches, much of which feels spiritually connected to that aforementioned “weird corner” of games—game art, artgames, small folkish experiments, and the like. People have been making interactive diversions out of existing technology for ages, from Medieval, paper-based text generation machines called “volvelles” to Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr. and Estle Ray Mann’s Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device—technically the first “videogame” based on manipulating the light beams of an oscilloscope—in 1947. Surrealists indulged in their parlour game of words and images, Exquisite Corpse, in the 1920s, as a way to spur creativity and the subconscious; computer art has existed as far back as the 1950s. In 1982, Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys created 7000 Oaks, a “social sculpture” which encouraged citizens of Kassel, Germany to participate in the work by planting trees in place of where Beuys had left as many basalt stones.

By the 1960s, artists belonging to the often participatory Fluxus movement desired to purge the world of the bourgeois “sickness” of “dead art,” which is to say the sort of art meant to hang in museums or homes and merely be admired. Dead art was to be replaced by the more participatory, dynamic, activist “living art,” which would help instill in people a worldly insight and empathy. Flash forward to 2000, and we find the Scratchware Manifesto, a resistance cry against the homogenizing practices of the games industry that takes much of its cue from the anti-corporate, tech-communitarian Cyberpunk Manifesto, echoing some of that anti-establishment and arguably populist art philosophy, proclaiming, “Death to the gaming industry! Long live games!”

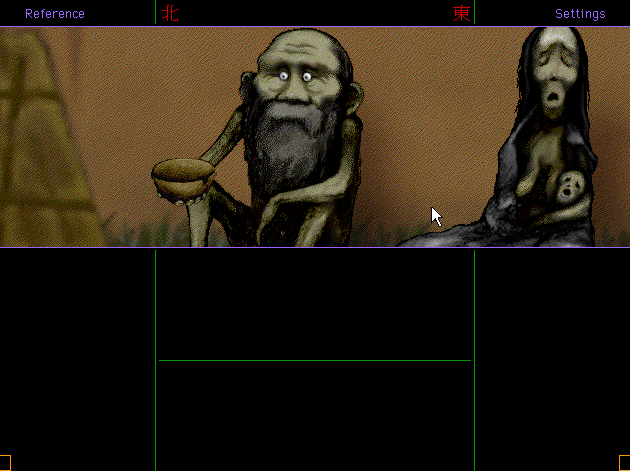

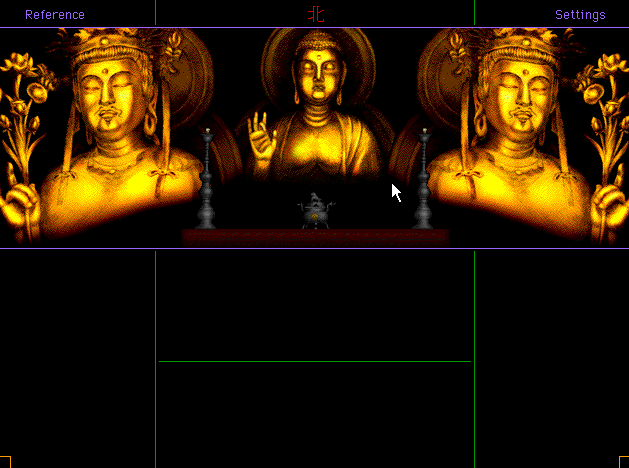

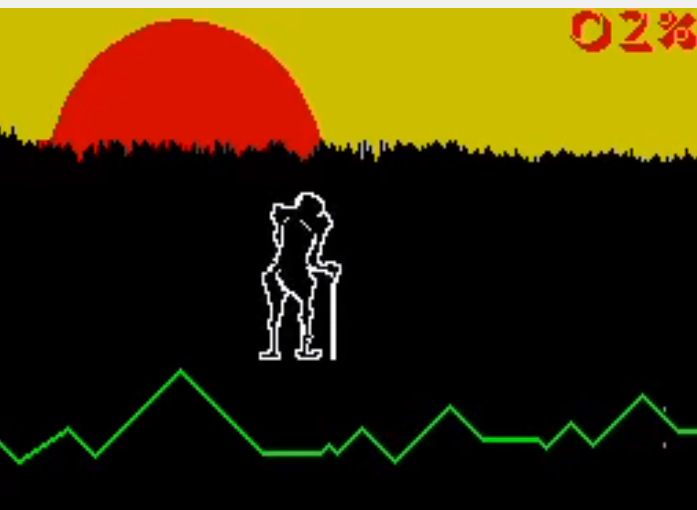

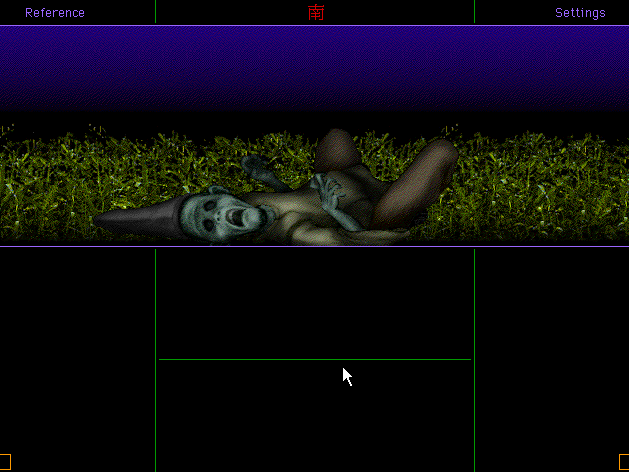

Still frame from Cosmology of Kyoto (SOFTEDGE, 1994).

If we take the official history of games at its word, we have what appears to be only a recent golden age of artistic experimentation and emotional maturity in games. The overwhelming cultural narrative posits that certain independent games—Jonathan Blow’s Braid (2008), Fullbright’s Gone Home (2013), or Supergiant’s Bastion (2011), for example—have succeeded as both critical and commercial successes and therefore represent a milestone in the actual artistic development of the medium. This view is understandable, but it’s also wrong. A sophisticated artistic treatment of games has existed since almost the very beginning of game development. In fact, there was once a time, from the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, where even games published by leading companies expressed more comfort and flexibility with the experimental and the avant-garde.

This is by no means to say that it was easier for artists to deviate from the formula much more than it is now, or that artists now are doing so less often. Many tasted rejection, commercial failure, and resentment, with or without critical acclaim. Even those who did not, like Keita Takahashi (Katamary Damacy), often found their works stripped of context and uncomfortably commodified, and their own role in their creation marginalized. These games continue to suffer from a severe lack of recognition in industry, academia, and popular discourse, and games made today which, like their predecessors, aim for the personal, experimental, conceptual, and affective often languish in obscurity. It seems surprising to say that the idea of the “artgame” goes back to at least the early 2000s, and that such works were being exhibited in spaces like the MASS MoCA. It seems even more surprising, given the hardened assumptions of the culture, that, as developer G.P. Lackey put it, “Artgames are as old as games!”

That creative risks were taken with more financial backing during this period is perhaps partly owed to the newness of the industry, and perhaps partly to its extreme instability. Ted Trautman notes in his New Yorker piece, “Excavating the Video-Game Industry’s Past,” that within the span of a year the industry went from booming to crashing and very nearly disappearing altogether. In 1982, the American company Atari, known for iconic games like Space Invaders and Pong, controlled 85 percent of the global videogame market. By 1983, Atari had flooded the market with games and failed to attract consumers to its new console, which led to a major fall from grace that took down a great deal of the industry with it. That same year, truckloads of unsold copies of games (most famously, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) were then infamously buried in the desert of Alamogordo, New Mexico. Nintendo is widely believed to have rescued the industry with its introduction of the Famicom (billed as the Nintendo Entertainment System) to North American markets in 1985, and European markets between 1986 and 1987. As a result, Japan became the epicenter of the games industry until the late ‘90s, when it began to migrate back to North America.

Still frame from Cosmology of Kyoto (SOFTEDGE, 1994).

Only a year after the Atari crash, an early attempt to deliberately treat a videogame like a work of art was released. In 1984, Automata, a little outfit from Portsmouth, UK, put out a game on cassette for the ZX Spectrum called Deus Ex Machina. Previous games from the company had been light-hearted and cheeky—such as 1982’s Pimania, in which the first person who was able to solve all the puzzles was awarded a £6,000 golden sundial. But Deus Ex Machina was different. The architect-turned-game designer, Mel Croucher, described to Polygon’s Colin Campbell how he had put his “heart and soul” into the game.

Still frames from Deus Ex Machina (Automata, 1984).

Deus Ex Machina cost a pricey £15 at launch and was played off of a cassette with an audio track to accompany it (you’ll have to use an mp3 and a ZX Spectrum emulator to simulate the effect on PC), and boasted some really impressive voice-over work from iconic British actors Frankie Howerd, Jon Pertwee, and Donna Bailey, as well as punk legend Ian Dury. It follows the story of a mutant, a “defective” life form made accidentally from a mouse dropping. The game recounts the Defect’s gestation inside of the “machine,” its growth, escape, accomplishments, failures, choices, and ultimately its death, all narrated by Pertwee and profoundly inspired by “The Seven Ages of Man” from Shakespeare’s As You Like It. The prose goes so far as to take direct cues from the play, often slipping into modified verse that blends Shakespeare’s words with the language of cybernetic dystopia implied by the title.

Through the audio, we are told this story of birth, life, and death, delivered with sometimes too-earnest poetry-prose by Pertwee, with Bailey as the gestating Machine, Dury as the jaunty Fertilizing Agent, Croucher as the Defect, and Howerd as the corrupt police officer attempting by turns to destroy or control the Defect. It is through their observations and instructions that the user is taught how to play the game. Often, in broken Shakespeare or rock ‘n roll lyrics, the game audio contextualizes the geometrically abstract visuals with meditations about morality, choice, contradiction, duty, and individuality.

What makes Deus Ex Machina so fascinating is how it engages with metatextuality well before the appearance of games like The Stanley Parable (2011) started to generate buzz. The life cycle of the Defect is “scored” by a percentage that sits in the top or bottom-right corner of the screen, and is apparently affected by how well the player follows the patterns in each successive stage, although the relationship between the two is not discernible. And it doesn’t matter, anyway. It’s a trap within the game that also chides the valuation of more “violent” videogame fare, and condemns the makers and promoters of it. It sets up and subverts an expectation that anything can be done to preserve or meaningfully quantify the life of the Defect. Only reflection can provide any meaning.

Deus Ex Machina wasn’t a financial success, despite some critical acclaim. Automata had fallen from the foremost developer in the UK to its office being sold to a dentist for 15 pence. The cost and scope of the project, including the robust packaging, has been identified as a culprit in the company’s closure, as was the rampant piracy of the game at the time. But there’s another element here as well: Croucher lamented, and continues to lament, the industry’s general reluctance to invest in and support artistic experimentation in games, stating bluntly, “I can't believe it's still people shooting each other and jumping up and down. It's crap.”

Deus Ex Machina may be seen as a cautionary tale about the prospects of artgames in the commercial videogame world. But perhaps there’s a silver lining to be found in the success of the Kickstarter campaign for the game’s sequel and the subsequent reopening of Automata. This game did eventually pay off, largely in the sense that it fomented a lasting admiration in the fans it had touched, and was arguably so ahead of the curve that it took a while before culture and technology could catch up with it. I discovered the game thanks to a tweet by independent developer Michael Brough (Corrypt, 868-HACK), who also found himself so enamoured of the game’s earnestness and beauty that it moved him to tears.

Perhaps a less beloved, though no less iconic experiment in the digital arts can be found in Takeshi’s Challenge (1986). Conceived by Japanese comedian and actor Beat Takeshi and developed and published by the Taito Corporation, Takeshi’s Challenge comes off as a game made by somebody who hates games, and for good reason. Beat Takeshi has openly admitted his curmudgeonly disdain for digital entertainment and modern technology, and the intense degree of involvement he demanded during the development of this game ensures it bears the mark both of his impish, Andy Kaufman-esque humor and snarling social commentary.

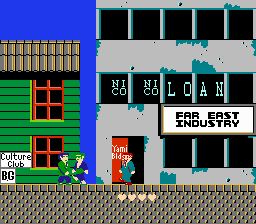

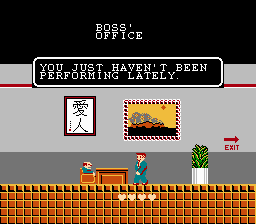

Still frames from Takeshi’s Challenge (Taito Corporation, 1986).

Takeshi’s Challenge puts the player in the shoes of a Japanese salaryman working at a middling company. A new game begins with the salaryman getting berated by his boss for underperforming. One may be tempted at this point to speak to their boss and receive a holiday bonus, but I’ll let you in on a secret—this would be a terrible mistake. That bonus will come in handy, but only after the player has left the building, gone to the bank, and emptied out and closed their bank account. The player is then supposed to go to the learning center to learn how to play the shamisen (a Japanese guitar), get blind drunk, and divorce their wife (at which point she will take half the money). Only then do guides suggest speaking to the boss, collecting the bonus, resigning, and leaving the building forever, but not before crouching by a ficus tree next to the exit to retrieve a stash of hidden bills.

Now, the adventure really begins: our salaryman gets into fistfights with Yakuza thugs at a pachinko hall (then robs them to buy his own shamisen), drunkenly sings at a karaoke bar (before once again getting into a brawl), receives a mysterious map from an old man as a reward for his toughness, flies to the South Pacific, and goes on a hidden treasure hunt. Upon finding the treasure, the player is greeted by Takeshi himself, who then playfully warns the player not to take playing the game (or presumably, any game) too seriously.

Still frames from Takeshi’s Challenge (Taito Corporation, 1986).

Without outside help, I would have thought that Takeshi’s Challenge was made up of no more than getting blackout drunk at bars until I had effectively blown all my money, lost my job, and left my family. This game takes the ideas of “adventure,” “exploration,” and “mastery,” and flips them on their heads, turning the experience into a slog, a mean-spirited joke. This is why I love it—or rather, the idea of it. This game is aggressively not fun and almost completely luck-based, which is intentional. Take, for instance, a segment in which the player receives the mysterious map, and has to soak it in water for an exact amount of time—without pressing anything!—to obtain its hidden information. There’s no hint provided in the game to help the player figure this out, and no way to discover the solution other than through trial and error or with a guide. As a matter of fact, the game is so unrelenting that players felt its original strategy guide was incomplete, and Taito released an updated version shortly after.

The game, released exclusively in Japan for the Famicom, was therefore never translated. To play it in English, I had to rely on a ROM-hacked version (that is, a version modified to alter or introduce elements of the game which were not there originally) run off of an NES emulator called FCEUX. This isn’t terribly surprising, since the game was universally panned, but I would be surprised if this was something Beat Takeshi didn’t expect. Even today, gaming culture has a hard time acclimatizing to conceptual challenges and formal subversions, tending to assume that a game which does not play as expected is also not designed as intended. Many still view experiments like this as somehow incomplete, or in extreme (and increasingly rare) cases, perhaps not even games at all.

But Takeshi’s Challenge, with the tools at its disposal, managed to accomplish a genre feat that many contemporary games struggle with. Only a few years ago, satire in games was a hot topic, and most interlocutors found themselves asking why it was that so much game satire seemed so flaccid, toothless, and self-defeating. I personally weighed in with the opinion that satirical context and framing—including of sensitive topics—was indeed possible, but that many games unfortunately expressed a degree of tone-deafness that rendered any claim to satire feel like a cowardly cop-out. But I now contend that the question of effective satire in videogames had already been answered twenty years earlier by a comedian who hates games. Takeshi’s Challenge mixes onscreen gags and dry, dark writing chock-full of misdirection and exaggeration with a fiendishly unfair approach to ludic design that points the finger back at the hubris and prejudice of the player. In its irreverence for the prevailing wisdom of gaming-as-entertainment of the era (and today), Takeshi’s Challenge may be viewed as an anti-game in the way that a Dadaist or a Fluxus artist would make anti-art. The joke was on us the whole time.

Still frame from Takeshi’s Challenge (Taito Corporation, 1986).

Deus Ex Machina demonstrated that games can be poetic, abstract, and tonally complex while telling an effective story, and Takeshi’s Challenge showed the capacity of the medium to make substantive, subversive social and formal critique. A game like J.J. Squawkers (1992), on the other hand, gave us a window into what’s possible for games in the realm of surrealist aesthetics and the evocative composition of digital architecture.

The latter two experiments with videogame craft appeared on consoles, and others on home computers. But a handful managed to show up in arcades, which prefigured the contemporary mainstream gaming landscape in their tendency to avoid risk and rely on established formula. J.J. Squawkers is one of the rare exceptions to that rule. The game takes maybe a half hour to play through, and in that time it blossoms from a fairly one-note, if whimsical, little arcade shooter into a pastel-shaded fever dream that feels like a trip inside the mind of conceptual artist Barbara Kasten.

J.J. Squawkers was distributed by Able and developed by Athena, a company specializing in shoot-em-ups. Most of the games designed for cabinet machines were designed with the intention of being profitable in sometimes-insidious ways. Having used the MAME emulator to run J.J. Squawkers, I was shielded from this reality thanks to automated credits and a pause button. Ostensibly, it’s a conventional arcade shooter: it hooks the player and takes them for all the quarters they have. The one review I managed to find about the game, at a site called Retro Collect, notes that the game lifts its ludic devices mainly from another strange arcade game, Ghosts and Goblins. Run, jump across platforms, shoot at patterned waves of enemies. Where the game really shines, though, is in its visuals, and so needs to be seen to be truly appreciated.

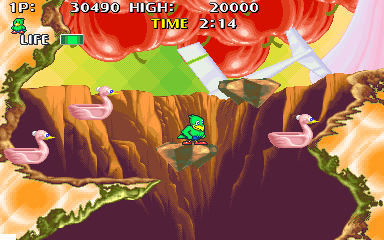

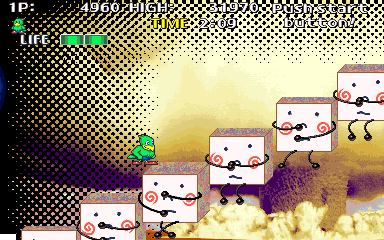

Still frames from J.J. Squawkers (Athena, 1992).

J.J. Squawkers can be played single or co-op, and puts the player in the sneakers of either a green raven named Ani, or a pink one named Ototo. With one or both of these birds, the player must restore balance to the pastoral land of Pistachioville by taking down flying squirrels, bellicose flowers, flying pegasi in space, cosmological symbols, ornery robots—and those are the creatures that don’t defy description. The looping chiptune muzak sets the tone for the absolute carnival that awaits even in the fairly easygoing, pastoral first stage.

By stage two, the rug is pulled out completely. A woman’s bent head directs the eye toward a red chair and a herd of pink buffalo. Pink swans lift the player to the next area and husk-like orbs crumble beneath their feet. Mazes that look like graphic errors push me left as plate-eyed blocks threaten to crush me. Futuristic, psychedelic cityscapes made of bubblegum or cut glass almost blend into the patterned floor beneath me.

Where this game excels, particularly with its 2D, side-scrolling plane, is in its ability to create depth and confuse the eye. Staggered layers and textures, from the smooth-faced polygons, meshes, and grids to staticky glitch art and pixelated or painterly figures give each stage weight and dimension. It’s cluttered and busy yet deliberate, and so makes for great virtual pastiche. At times it’s not clear what’s solid footing and what’s background, or what may be an enemy until it tries to kill you, but it all works to serve the dreamlike and utterly absurd nature of the game. Learning how the spaces work helps the player actually play, but the spaces also engender a deeper appreciation of the space and how it is put together. There’s a conceptual element in that this game wants us to feel its textures and find the logics in its compositions, without having us worry too much about the validity of what we are doing.

Still frames from J.J. Squawkers (Athena, 1992).

Evocative composition, aesthetics, tone, and storytelling in a ludic context continued to develop in published videogames well into the mid-’90s. SOFTEDGE’s 1994 release, Cosmology of Kyoto, arguably stands as one of the great early syntheses of all of those elements, as well as a fascinating mix of genres. The game mixes historical fiction with psychological and body horror in a way that’s rich, alive, and deeply discomforting. Notably, the late Ebert, who famously dismissed the entire medium as crass entertainment, wrote of the game for Wired in the year of its release:

The richness is almost overwhelming; there is the sense that the resources of this game are limitless and that no two players would have the same experience. I have been exploring the ancient city in spare moments for two weeks now, and doubt that I have even begun to scratch the surface. This is the most beguiling computer game I have encountered, a seamless blend of information, adventure, humor, and imagination – the gruesome side-by-side with the divine.

To run this game today, I installed an image file on my Windows 3.1 DOSBox virtual machine. To get the machine working in the first place—in order to play the Prince game, as a matter of fact—I enlisted the ever-patient critic and writer Jenn Frank. About two years prior to helping me, Frank had already written out a guide for those playing the game on Mac, much to the delight of Ebert himself.

Still frames from Cosmology of Kyoto (SOFTEDGE, 1994).

The game, presented in an unusual, cinematic widescreen, makes use of a mix of influences, from Buddhist and Shinto allegory to Yurei-zu painting to ero guro manga. It takes place in ancient Kyoto around year 900 and follows the explorations of a traveler through this dilapidated, miserable city where the poor beg and suffer and the rich hide in palaces and temples. I should also mention, the place is haunted by ghosts, terrorized by hell demons and partially razed by a meteor that knocks down yet another piece of barely-serviceable wall. I begin the game by customizing a character and am dropped naked into a field. I’m left to fend for myself, stealing clothes and money off a corpse and slowly making my way to the city walls.

On my journey, I meet a legendary warrior with whom I trade a talisman for a sword, a procession of sick, disillusioned beggars and uncaring upperclassmen, a seductive maiden, the ghost of an ancient noble, a gang of murderous thieves, a Buddhist monk who tries to save my soul, indulgent and out-of-touch courtiers, and a horde of malicious, bloodthirsty demons. It doesn’t matter if I die, because I will always reincarnate into some new body—some random combination of features—and have the opportunity to retrieve my clothing and money sack from the last shrunken, gray corpse I accidentally walked into in the jaws of oblivion. For a brief instant I will see heaven or hell, depending on my hidden “karmic score,” and then come back to Kyoto.

The tone, atmosphere, and imagery of scenes make for moving and memorable moments. Of the handful that really stood out for me in my last playthrough, there was one that brought together all the aesthetic and thematic elements of Cosmology of Kyoto in a beautiful, disturbing fashion.

While passing through Kyoto’s ramshackle market, I come across a young woman held captive by two brute men. They’ve accused her of thievery and are threatening to kill her while she pleads her innocence. At that moment, I draw my sword, scaring off the men and earning the woman’s trust and admiration. The close-up on her face highlights her relief and gratitude. She offers to give me, a weary traveler, a place to stay for the night and asks me to follow her to the location. Of course, just about every household in this town is haunted or infested with demons, and this one is no different. From the shadows a demon rises, lurches into the foreground and grabs the young girl from behind. The scene fades out to the sound of her screams.

The demon howls, commanding me to leave. On my way out of the home, feeling my way through the darkness, I find her body. It’s dessicated and bound. Her face is twisted with fear and sadness. The game’s widescreen resolution makes the space feel more narrow and claustrophobic. The morbid eroticism of her bound body evokes ero guro—a 1920s Japanese manga style focused on a combination of the sexual, surreal, and grotesque—and particularly the bondage- and demon-preoccupied works of artists like Toshio Saeki. The supernatural nature of her horrific death—and of the certainty of her suffering, trapped soul—contains strong notes of Yurei-zu, particularly as seen in the work of Sawaki Sushi or Yoshitoshi.

Despite critical acclaim in the West, Cosmology of Kyoto was ultimately a failure in Japan, especially among residents of Kyoto who didn’t take too kindly to the grim depiction of their city. But it’s still worth considering for the standard it sets, both as a 3D adventure game with so many well-oiled moving parts and as a genre hybrid that manages to enchant, compel, and confront the player on multiple levels while letting them explore at their own pace.

The games mentioned here only scratch the surface; there’s a wealth of artgames that existed well before 2008 that get excluded from the conversation despite their contributions. One could argue that the reason so many of these creative deviations remain consigned to the fringe of videogame history is because they were marginal accomplishments in their day, or enjoyed moderate success at best. This is only half true. While the games I described all have a relative lack of commercial success in common, many have achieved iconic status even among non-art-minded gaming enthusiasts. EarthBound, a satirical sci-fi role-playing game designed by actor and essayist Shigesato Itoi and released for the SNES in 1994 is considered a massively influential game. The multimedia artist Osamu Sato would go on to design LSD: Dream Emulator, a first-person 3D game for Playstation released in 1998 that is steeped in surreal imagery and symbolism, and is considered by many to be a tour de force regarding its use of space to imply a dreamscape. These works and more belong to an era of major published projects found on consoles, home computers, and in arcades, and for a brief time, it was something close to normal to be weird.

To fully embrace and develop the experimental potential of games, and the artistic potential for technology in a way that’s socially beneficial, there is a need for broad material resistance to neoliberal effects on labor (e.g., universal income, unionization, and games-inclusive social funding for the arts). That in itself reflects a deeply complex, structurally broad set of problems that need to be resolved at the macro socioeconomic level, and are difficult to address in the videogame industry due to its structure and lack of a labor history. This is an industry which as a whole has demonstrated a repeated lack of concern for games as artistic or historical objects. This is an industry in which independent developers still have to rely on hit-making and windfall success or find something else to do. For that matter, this is a culture in which most people who play games are completely alienated from the labor involved in making them, from resource extraction to manufacturing to development.

At least for starters, a cultural shift that begins with a historical understanding of games-as-art which doesn’t treat this reality as anomalous, “fringe” or somehow contradictory, will open up our contemporary understanding of the form, and let in scores of artists who’ve been excluded from consideration. There are some promising endeavours to these ends, including independently curated archives, critical journals, and some rather radical creative collectives.3 People doing this kind of work often do so as a labor of love, and operate under relative precarity, frequently at risk of having to shutter their platforms or disband their collectives. A cultural value shift can perhaps help to circulate more capital, both financial and social, in the direction of these initiatives and individuals. The more permanent shift, however, will be the one that embraces videogames not just as commodities but as part of a history of interactive and digital art. This understanding can help us situate games as an art form that can and should enrich our lives personally, communally, and even politically. It could drastically change our relationship to technology and to the arts.

The idea that games can be expressive, thoughtful, and socially impactful is not new, and the longer we continue to believe it is, or that this is merely a byproduct of advanced technology, the more we will continue to sideline the experiments that make growth possible. We limit ourselves needlessly by ignoring this long history, and the creative work of those who sought to create meaning from this strange, newish form. We leave the terms of the discussion in the hands of those who see interactive digital art as good for no more than passive entertainment commodity or, at worst, corporate and state propaganda.4

Another future is possible for the form and all the people working in its orbit. We excavated videogaming’s past to trace its failures once; we can do so in a more figurative sense to trace its most intriguing contributions and, hopefully, point to a better alternative reality.

Footnotes:

- The first “electronic game” is technically Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr.’s and Estle Ray Mann’s 1947 invention, the Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device. In 1958, William Higginbotham released Tennis for Two, which was played on oscilloscopes and analog computers, and some argue that this is in fact the first videogame. Spacewar!, while technically the third digital game in this timeline, is still arguably the most influential and iconic of the three.

- Although coinage of the term “artgame” is sometimes attributed to artgame designer Jason Rohrer, its usage goes back to at least 2003 when new media artist Tiffany Holmes referred to it in her paper, "Arcade Classics Span Art? Current Trends in the Art Game Genre." In John Sharp’s 2015 book, Works of Game, he distinguishes between “artgames”—games made with the intention of being art while still contextualized as games—and “game art,” which refers to the use of videogame iconography and technology as raw material by artists working in other domains.

- Archiving initiatives include the Internet Archive’s preservation of over 2400 DOS games to their collection, a few of which critic Cara Ellison sardonically dove into for The Guardian. Sites like My Abandonware and Abandonia work to preserve games which are no longer easily available or supported by their original publishers, and the existence of accessible, art-oriented books, journals (like The Arcade Review, for which I am a writer), development collectives, zines, and so on about or inclusive of games help to popularize some of this alternative history. More overtly political attempts to connect the form to the outside world, like Jacobin’s sponsorship of Subaltern Games for their project, No Pineapple Left Behind, also demonstrate the medium’s capacity for cultural, communal, and educational relevance, although a lot more can be done in this area.

- I refer to recruitment tools like America’s Army. I also refer to Simon Parkin’s investigative piece, “Shooters: How Video Games Fund Arms Manufacturers,” the industry’s general obfuscation of its relationship to conflict minerals, and much pettier situations like the “Dorito Pope” affair that point to the deeply commercialized facets of the medium.

Top image: still frame from Deus Ex Machina (Automata, 1984).