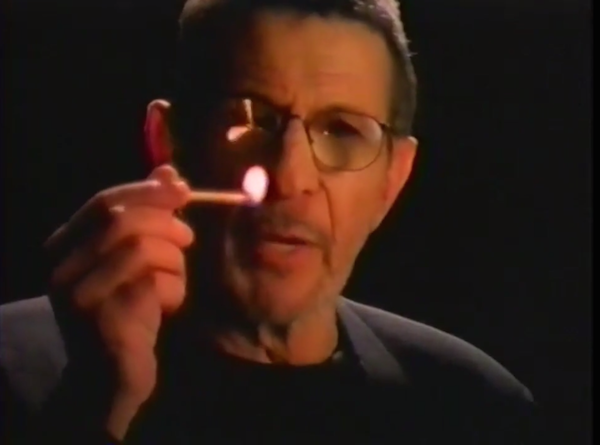

Screenshot of Leonard Nimoy in Y2K Family Survival Guide (1999).

In December, Perry Chen organized a panel discussion at the New Museum (copresented with Rhizome and Creative Time Reports) exploring the phenomenon and legacy of the Y2K bug, as part of his ongoing project Computers in Crisis. Along with a presentation of books and video clips from the time, he assembled three Y2K experts to share their own experiences of preparing for 1/1/00, at which point many computer systems were expected to interpret the two-digit date as "1900" rather than "2000," with harrowing results.

The event was a fascinating narration of an overlooked moment in technological history. If Y2K has been remembered as a "non-event," a hysteria and a farce, is that because it was an overblown threat? Or is it because the preparation for it was successful? In particular, the Y2K compliance effort was characterized by a sustained, collaborative effort to understand and update the aging software that had been lurking in many of the world's most crucial business and public sector computer systems. (As Chen wrote for Creative Time Reports, even the US and Russia worked together to prepare for the unknown, jointly staffing a Y2K command center in Colorado.) It was not only a collective attempt to understand and manage the risks of that dependence, but also a public discussion about our dependence on complex technological systems—a public discussion which is sorely needed today, as if you needed another reason to miss Leonard Nimoy.

The panelists (David Eddy, who coined the term "Y2K," Margaret Anderson, formerly of the Center for Y2K and Society, and Shaunti Feldhahn, author of Y2K: The Millennium Bug—A Balanced Christian Response) all had interesting stories to share, but the most memorable moment of the night belonged to Anderson:

Margaret Anderson: A whole lot of people on a global basis started working on it, and sharing information. There were really great lessons learned on how to address a complex, unknowable problem, and it was cooperation, collaboration, and a lot of information sharing. There was a huge undercurrent of engineers and programmers, and people like us who found a problem in a piece of equipment or in a software package, and let all of their networks know that it had that problem, and "here is the fix." They didn't tell their bosses they were doing this, they just did it because it was the right thing to do.

It was incredible around the world. There were regional meetings sponsored by the UN and helped a lot by the world bank and the US government, of regions of Africa and regions of South America; countries getting together and recognizing "you have the electrical infrastructure my country is dependent on…or, you have the water source my country is dependent on…let's talk about it," and "are you ready for Y2K?"

Perry Chen: Y2K was a moment where a large number of women were heading these projects...

MA: I was mostly familiar with the federal government agencies, and I was a woman in technology, and really aware that there weren't many around me. And what I found with Y2K was all of a sudden I'd be in meetings, and so many of the program managers and the project managers were women. And they were there because it was not a good career move to be in Y2K. It was short term. If there were problems, you were going to get blamed for them. You didn't have the authority to really make the changes. So many people wouldn't take the responsibility, so all of a sudden there were a lot of women around, and I saw an unprecedented level of cooperation and information sharing… really. It was beautiful. (audience laughs/claps).

Watch the edited video of the event here: