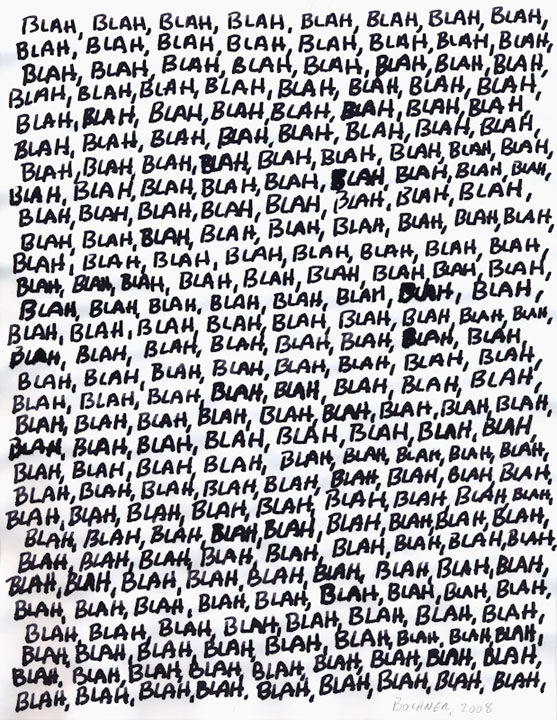

Mel Bochner, BLAH, BLAH, BLAH (2008)

A version of this essay was initially written for a panel discussion with Pitchfork's Ryan Schreiber, Isaac Fitzgerald from Buzzfeed Books, and LA Times art critic Christopher Knight at Superscript: Arts Journalism & Criticism in a Digital Age, a conference at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Watch the panel discussion here.

Look at the title. I'm asking has, not "how." Contemporary art is still in the early stages of the digital shift that other industries have already experienced. To better understand what might be happening to art criticism, we should look to other fields and assess the structures that have developed as a response to the internet's effect.

There are two facets to this "internet effect": the first is in publishing and circulation, the second in the way this dissemination shapes a discipline and the discourse around it. Music and literature experienced the digital shift in a much more extreme way than contemporary art has thus far. This experience began with circulation—the adjustment from object to mp3 and from independent, or even megachain bookstores to Amazon—but continued with an altered discourse that poses really valid questions about the function of criticism. I'll call it "service criticism." In a nutshell, "service criticism" is criticism that's discovery-oriented. Criticism that assumes the reader who is looking for recommendations.

Take Pitchfork, for example. I remember the first time I heard of Pitchfork. I was a teenager and I had a friend who spent his days reading Pitchfork reviews, then (excuse the illegality of the following) downloaded all the albums he thought he'd find interesting in order to listen to them. (The embrace of streaming technologies helps with the legality question today.) That's a great use of criticism: as a direction, pointing to the good in the midst of overproduction.

The use of a word like "service" sounds las if it indicates a value judgment, and one that I'm not making. I'm not making it because, as an art critic, I don't write in an industry that has generated much service-criticism yet. When I write about an exhibition, I often write for print publications, which means the show has closed a while before the review was printed, and so I'm already writing in past tense. I also assume that whoever (and however small) my audience is, few of them—almost none—are art collectors who are reading the review as a way of assessing a given artist's worth.

(L-R) Christopher Knight, Ryan Schreiber, Isaac Fitzgerald and Orit Gat. (Superscript 2015. Photographer: Gene Pittman. Courtesy the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis)

For me, reading art criticism in print magazines is similar to the way I read food reviews, because I don't go out to fancy restaurants. I love descriptions of kinds of food I've never tried and I never stop making the joke that my favorite thing about living in New York is that I live in a city where a review like the following makes sense:

Once in a while, Montmartre still gets a case of the blahs. The dressing on a wax bean salad, allegedly a tahini-soy vinaigrette, made no impression, and curls of raw hamachi with diced apples didn't rise above routine.

This is from the New York Times review of Montmartre, a French restaurant in Chelsea. "Curls of raw hamachi" are routine for some people. I'm never going to eat at Montmartre because their roast chicken costs $26 (I did my research and looked up their menu). If I'm never going to eat at Montmartre, why read the review? Because it is an analysis of something I am interested in: food and the culture around it.

Art reviews in print magazines are almost similar: their focus is something ephemeral, something that most of your readers won't buy, or an exhibition they won't see. So the topic is writing about experiences—the wax bean salad, the exhibition—but also writing about a larger discourse. Of course, discovery-oriented service reviews can also be reflections on a larger discourse: the New Yorker reviews that "could be half over before he got around to talking about the performance under review" (that's a positive thing, see Daniel Mendelsohn's serenade to criticism), the London Review of Books format of essays that take up three books on a similar topic and fuse them to a single piece of writing that both summarizes and opens the books' subject to further discussion and possibilities.

But in the popular imagination, service reviews have a much more specific role: to act as a vehicle for recognition, as recommendations. "Should I see Mad Max? Let's check what the Times said about it." "Have you seen that review of 10:04? I really want to read it." Search habits have only enhanced this sentiment: when you look for information, you get reviews. Reviews do well on Google: when you Google "Ben Lerner 10:04," the first result is Amazon. The following nine (so the whole first page) are reviews: the New York Times, the New Republic, Bookforum, the Guardian, the Telegraph, and so on. The next page: an interview with Lerner in The Believer and his Wikipedia page. (Something like 95% of Google searches ignore the second page.)

The above explains part of my claim that digital circulation changes the discourse. To return to my not-a-judgment sentiment: I think the service review comes with an immense responsibility to analyze the market, to give context to what is popular beyond best-seller lists. (Though yes, I recognize the internet's feelings toward lists.) Service criticism thus has a responsibility to include both positive and negative criticism. When a publication decides to focus on positive reviews only, this usually reflects a presumption that people look to reviews as recommendations. The issue with that is it means ignoring another important role of criticism: to keep the market in check. Thus Jerry Saltz's coining the term "zombie formalism" to describe the trendy—by which I mean, marketable—process-oriented abstraction so successful in New York of late, is valuable even though his argument (which focused on sameness rather than financial role) was weak.

Audience members at Superscript. (Superscript 2015. Photographer: Gene Pittman. Courtesy the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis).

Where is the criticism-discovery link that we associate with so much online reviewing in contemporary art criticism? My sense is that the internet encourages service criticism, especially because of search engine economics. Think about Artforum.com's reviews section, which is framed as "picks." While the in-print reviews for the magazine introduce a multiplicity of voices, both negative and positive, the online reviews are shorter, published more quickly, and generally positive—that is, they are recommendations. Artforum.com's Picks have different goals than the magazine's reviews section: they aim to offer timely, original analysis of work while alerting readers to worthy exhibitions as they happen.

Criticism generates cultural capital, which in turn is translated into capital. To only publish positive reviews means to forego this responsibility. The fact that advertising and revenue models are changing because of the internet only makes this more crucial, as a not-so-glowing book review may translate to a lower clickthrough rate to Amazon. But what "travels" better, positive or negative reviews? I haven't had a means of confirming this, but my guess is that the negative ones do. I've never seen a glowing review go viral, but I have many a negative one do so, in the style the New York Times food critic Pete Wells is best at. There seems to be a tone—an all-guns-blazing review—that is so entertaining that people want to share it.

But is sharing participation? What is the meaning of going viral? The terms of engagement are such that every tweet, reblog, and like is another coin in the coffers of a number of companies: whatever social media platform, the publisher, the advertising agency. When the way we interact online is already so fraught in monetary terms, for something to go viral just means to activate this system over and over again. Sharing is participating in the economy of scale online. The fact that the web allows for smaller-scale operations has created a myth that audiences self-organize online (that "if you post it, they will come"), which is often untrue. As in television and legacy media, audiences tend to congregate in the same places, usually the ones underwritten by huge corporations. We see the effect of that tendency in the cultural sphere with sites like Lithub, which is a conglomerate of publishers, booksellers, agents, and so on, producing content together. From their about page:

Literary Hub is an organizing principle in the service of literary culture, a single, trusted, daily source for all the news, ideas and richness of contemporary literary life. There is more great literary content online than ever before, but it is scattered, easily lost. With the help of its partners—publishers big and small, journals, bookstores and non-profits—Literary Hub will be a place where readers can return each day for smart, engaged, and entertaining writing about all things books.

The assumption is that these organizations are stronger together. It just seems, well, you can imagine: more generalized, more popular, more eyeballs. That's why aggregators like Rotten Tomatoes become so influential: they centralize the discourse.

All in all, much of the way we participate is parceled to two—the personal feedback (the positive buttons, like, fav., etc.) and the "useful" (as in Yelp: Was this review "cool," "useful," or "funny"?). I'm interested in the "use value" of crowdsourced criticism because it is one of the few new forms of writing that developed on the internet. Which seems reason enough to take it seriously, though the status of crowdsourced criticism is still quite fraught, belittled as it is by more traditional critics.

People who have strong reactions to a work—and most of us do—but don't possess the wider erudition that can give an opinion heft, are not critics. (This is why a great deal of online reviewing by readers isn't criticism proper.)

—Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker

and

By offering an alternative deluge of fans' notes, angry sniping, half-baked impressions, and clubhouse amateurism, the Internet's free-for-all has helped to further derange the concept of film criticism performed by writers who have studied cinema as well as related forms of history, science, and philosophy. This also differs from the venerable concept of the "gentleman amateur" whose gracious enthusiasms for art forms he himself didn't practice expressed a valuable civility and sophistication, a means of social uplift. Internet criticism has, instead, unleashed a torrent of deceptive knowledge—a form of idiot savantry—usually based in the unquantifiable "love of movies" (thus corrupting the French academic's notion of cinephilia).

—Armond White, in First Things

The position of the trained, published critic in support of the field seems irrelevant to me. Yelp, Amazon, or Tripadvisor reviews circulate in a different economy of meaning: the quick, the recommendation, the service criticism that offers little more than service. It's useful for what it is, though it is defined by being easily monetizable unremunerated labor. For its position in the service of service criticism, crowdsourced criticism also messes with predetermined economic structures, especially in the art context: scarcity.

One of the strongest statements in a review is its subject. For every review a magazine runs, countless exhibitions, books, or films (this seems especially pertinent with the New York Times recent announcement that the newspaper will no longer review every film that opens in New York City)went unnoticed. Not having space to cover everything is one of the attributes of the magazine. It's selective. Yelp, meanwhile, could potentially include every storefront in New York City. How do the economics of criticism change when something traditionally scarce becomes so abundant? Crowdsourced criticism activates both monetary systems predominant in the digital economy: scale, participation.

But crowdsourced criticism does not answer the market's need for reliable service criticism. The film industry, for example, relies so heavily on the cultural capital incurred by a print review that in order to qualify for the documentary film Oscar, a film has to be reviewed by either the LA Times or the New York Times. Nor has service criticism, with its focus on the positive, the recommendation, risen to the level of influence described above.

This essay opened with a discussion of dissemination and the way digital culture has modified circulation in music, literature, film. The main reason contemporary art has not been as impacted by the digital turn is that most (sellable) art object is not infinitely reproducible as the digital file (mp3, .mov, .epub) is, or even the physical, but widely distributed real object is (vinyl record, printed book). This is changing with new forms, websites, and organizations dedicated to the presentation of art online. With this shift, art criticism will have to develop new ways—or at least, new outlets—to analyze it. I, for example, have a lot of hope for the mailing list as a form we have yet to exhaust (e-flux notwithstanding) as a way of surpassing digital advertising models as we know them (by which I mean, selling your data, bundled, from one site to the next). To really react to the changing platforms for art online, we need new models for criticism. Most of the structures I've discussed relate to an ad-revenue-based internet. I think there is no bigger disappointment on the internet than free culture: too often, it has meant that if the user won't pay, the advertiser will. The result of this is a digital economy where websites all aggregating and packaging the same material hoping to attract as many eyeballs as possible and with those, advertising revenue.

It may be discouraging to close on an optimistic note that basically means, "you're gonna have to pull out your credit card/sign in with your Paypal/Apple Pay/whatever digital wallet we'll all be using use at some point in order to get the kind of criticism you deserve." But it's true. The more the internet veers toward paid models the better off we'll be. I don't know if art criticism will catch up with music and literature before or after this happens, but I know that service criticism will not serve contemporary art. It's not enough.

Christian Jankowski, Review (2012 – sealed bottles containing hand-written texts by art critics about this work, sent in response to a request from the artist); installation view as part of the exhibiton "Heavy Weight History" at CCA, Tel Aviv (2014).