Robert M. Ochshorn, The App and the Territory (2014)

These days, Facebook is so widely used that opting out constitutes an act of defiance of the norm. The refusal to participate can be made for personal reasons, but there is a sizeable group who do so as a protest of the corporate control over interpersonal communication. In a 2014 blog post, Laura Portwood-Stacer used the metaphor of "breaking up with Facebook" to describe:

active refusal as a tactical response to the perceived harms engendered by a capitalist system in which media corporations have disproportionate power over their platforms' users, who, it may be said, provide unpaid labor for corporations whenever they log on.

The burdens placed on Facebook's users are certainly significant; they include not only cognitive labor, but also online harassment, dataveillence, and the performance of the profile–which is pulled in multiple directions, at the same time increasingly sexualized (pulled into online dating sites like Tinder) and entrepreneurialized (pulled into sites like Airbnb), even while the display of the body within the profile is regulated in punitive, sexist fashion.

One might question whether opting out constitutes a successful removal from the object of concern, or rather, just another performative act amid the impossibility of ever getting off the grid. In this piece, I want to use the example of the Facebook Group to argue that opting out also involves a disavowal of crucial forms of vernacular culture and solidarity. Through collective, thematic riffing, Facebook Groups offer a crucial form of contemporary social and political experience.

Facebook Groups have a low barrier to entry–for example, one doesn't need to understand domain registration or hosting to build a large network. Domain registrar GoDaddy claims 51 million domain names, but there were some 620 million Facebook Groups as of 2010. More than a third of Facebook's active users participate in Groups; some Groups are public, while others require new members to be approved by an admin. Once in, Groups facilitate communication among members via messages and posts, which may also be moderated. Groups are often established around particular topics, which are can be wonderfully specific: see, for example,"Medical Fashion Quarterly" and "Simpsons Shitposting," and a trove of Groups compiling aesthetic categories including the internet-of-things inspired, "HOMECARE AESTHETICS: Environment and Object, offspring of "CORPORATE AESTHETICS: Environment and Object," that bring iconic anomalies and internet garbage to the kitchen table of your feed so you don't have to waste time in Google image search.

The tech world calls these micro-media environments "communities," as it does many things. The most interesting Facebook Groups are often collective efforts; highly organized spaces that facilitate structured randomness. Take "Cool Freaks Wikipedia Club," a Group of about 35,000 members that has achieved cult status, with around 35 additional splinter Facebook Groups, and that was recently featured at Adrian Chen's Brooklyn live-presentation series IRL Club. Cool Freaks' theme is the re-posting of obscurantist Wikipedia articles, drawing members who enjoy a specific type of media consumption– going down "Wikipedia holes"– clicking from one interwiki-link to the next in search of joy-inspiring esoterica. These kinds of Groups are as vital to the culture of our time as any book or magazine.

Not incidentally, the Cool Freaks Facebook Group has been innovative not only in its choice of topic, but also in its establishment of ground rules on identity inclusion and language and its strict banning policies for "furthering / arguing an oppressive mindset (racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, classist, et cetera)." A recent blog post by Sally N. Marquez, "Week Two: Communication in Digital Spaces" contextualized Cool Freaks' Rules as exemplifying how Groups use "mediated communication in order to enhance a specific type of social interaction, as well as build and reinforce social structures." Cool Freaks' ground rules speak to the power of the Facebook Group to foster intentional, inclusionist practices.

Ben Wilson, one of the moderators or "mods" of Cool Freaks Wikipedia Club Facebook Group, tells me via email:

The moderation and rules cater to the disenfranchised as opposed to less moderated communities. This has been the guiding principle behind our moderation team as we do not want to suffer the same problems of other Groups. While publications like Vice have called this "fascist hypersensitivity," we remain firm on this position… While the size of the Group builds into a spectrum of political engagement whether online/off—or direct action and other forms, the online forum allows us the chance to bring central issues to the forefront as Leelah Alcorn and Ferguson unrest via the pinned post option… The Facebook Group offers us the opportunity to give back to the community whose core membership leans towards the radical left besides a prominent number of the moderation being activists themselves.

Cool Freaks shows that even a seemingly frivolous Facebook Group may be as much about solidarity-building and collective self-governance as it is about playful, weird content. Amid the failure of Facebook alternative sites like Ello and Diaspora to realize viable alternatives despite significant enthusiasm (and capital investment), Facebook Groups have led to more formal efforts to organize or lobby, and have played an important function in raising political awareness—all this, despite the burdens placed on users by the corporate platform they use.

The "New Platforms" Model

I'm feeling fatigued by the repeated attempts of alternative media to "build new platforms" over the past few years, always seeming to posit that our current sharing platforms are not good enough, or not radical enough, and that more platforms are needed. But the creation of new digital platforms is not necessarily synonymous with empowerment, and may instead splinter existing groups into a confused multiplicity of channels usually characterized by a high barrier to entry or lack of discoverability.

Are platforms publics? Conversations defining the public sphere in the context of contemporary mass media production might help answer this question. Jürgen Habermas identifies the public sphere as a historical condition emerging in the late 18th century, spurred by the merger of state and private life under capitalism concurrent with the abolishment of feudal states. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962) describes how capitalism's rapacious reach further into the private, social sphere is responsible for the transformation of the traditional forms of political expression that took place outside the home, into a participatory media landscape characterized by literary cultural/sociological exchange among competing constituencies, which vie for representation. These constituencies stretch into the most private aspects of our social lives in a way not possible under feudalism. In this way, contemporary publics are tethered to evolutions in free speech, where developments of discrete media platforms constitute our most viable forms of representation and expression even as they are entwined with co-opting technologies.

Geert Lovink has drawn from such canonical approaches to explore the creation of alternative publics through internet-based media activities informed by radical, theoretical frameworks, and their subsequent canonization. The noun and adjective "tactical media" describes such alternatives to mass media, where the strategic use of media to intervene in the oppressive, corporatized technologies of the majority, represents a radical approach. Lovink is co-founder of the new media mailing list <nettime>, founded in 1995 at the Venice Biennale. <nettime> is a moderated discussion with a more decentralized approach: most messages are written by participants, and moderators play a minimal role. The list of rules sent to new participants is much looser than those of the Cool Freaks Wikipedia Club; <nettime> moderator Pit Schultz once noted that "The less the moderator appears the better the channel flows." <nettime> is a space of consensus-building and the structured inter-pollination of ideas; it assumes a shared sense of purpose on the part of its users that public Facebook Groups generally do not. The list is quite careful to use like-minded organizations for its server space, ensuring that a hosting service will not exercise censorship.

Along these lines, one argument for the creation of new platforms would be that platforms created by corporations like Facebook or Gmail prevent the kind of autonomous, organic, social organization that characterizes the public sphere at its best. Then again, the "public sphere" has never meant unadulterated, uncensored speech for all, outside of existing social structures. Communication and connectivity exist under gendered, colonial surveillance reinforced by unsympathetic administrative protocol, pre-dating the internet. Full participation in the public sphere is dependent on citizenship, which is itself deeply enmeshed in xenophobia and policing. Citizenship attaches endless paperwork like the Social Security Number Card and the Driver's License to personage as a way of managing bodies to make them more readable by the state. These numbers, increasingly required in everyday transactions, double as state tools: to target and deport illegal and unregistered immigrants, to accumulate pre-emptive police intelligence, and to surveil.

Mailing list-based tactical media projects rely on the corporate, populist technology of email (and often the Google environment) to foster critical perspectives of the very platforms in which they disseminate information and vie for representation. For the <nettime> mailing list's 20th anniversary, its hosts sent around an April Fools message playfully suggesting that it would be shutting down; the message included a line that seemed to acknowledge an implicit elitism in its stance: "really, who cares what a bunch of straight white cis guys—which is 95% of the list's traffic—think about those things? Really." Of course, <nettime> has not shut down, and continues to host an active, vital discussion much as it always has, but the joke was an acknowledgment of the barriers to access that shape putatively open online discussions such as <nettime>.

Responding to the increasingly omnipresent Facebook, recent years have seen several notable attempts by institutions to build their own software-driven platforms for online conversation away from the platform. Rhizome was a pioneer in this, shifting in the mid-2000s from a mailing-list centered model to a blog with comments and profile pages, almost a quasi social network that mirrored Facebook saturation.

A critical viewpoint could also construe this gesture as an institutional strategy to resist critique by subsuming it. e-flux Conversations isn't a Facebook Group because its wants to avoid the many constraints of that platform, but essentially functions as a familiar mirror of Facebook's conversation style. In this way, it presents the problem of duplication, contributing to the contemporary problem of having to many platforms to choose from to post an idea, which usually results in laborious cross-posting.

e-flux Conversations and <nettime> represent two kinds of alternatives to the dominance of the Facebook Group; there are many more. The argument on behalf of such alternatives is clear: when communication is monopolized–as it is on Facebook—users cede significant control. Some of this control may be clawed back by using platforms and e-mail hosted with non-profit organizations, which at least make regulation and surveillance a bit less convenient, or using software platforms developed by for-profit organizations with compatible values.

Meanwhile, a 2013 Pew Research Center study found that 64% of adults use Facebook, while 30% of Americans use it as their primary news source. Its scale and omnipresence make Facebook Groups an ideal environment for vernacular culture as well as consciousness-raising and political organizing. Embracing Facebook and its corporate aesthetic doesn't have to be read as giving in, or as an accelerationist acceptance or even pursual of corporatization. Rather, in spite of seemingly insurmountable barriers like corporate centralization, solidarity and resistance can be, and are perhaps most likely to be, forged from within the very structures that seem most totalitarian.

The Anti-Facebook meta-discussion on Facebook

These days, Facebook's publics are responsible for "loading the canons" of the political subconscious, and we must be delicate in not dismissing their cultural value. Orit Gat in her recent Rhizome essay, "Has the Internet Changed Art Criticism? On Service Criticism and A Possible Future," argues that crowdsourced criticism "messes with predetermined economic structures, especially in the art context: scarcity." But it also produces some exciting new ground as the smaller, granular levels of conversation become fodder for the public sphere.

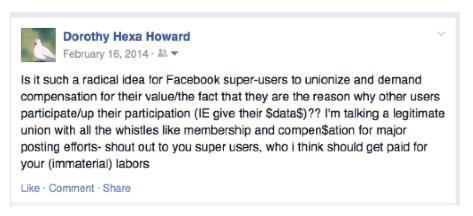

On February 17, 2014 I started my first Facebook Group: Immaterial Digital Labor. Having recently read Tiziana Terranova's 2003 essay, "Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy," it started as just a status update:

I started the Facebook Group partly as a web of disseminating critical writings with a critical, activist agenda springing from Terranova's paper, but also partly as a social experiment. It became evident early on that the Group was built with a sense of irony, insofar as it sought to call out discrete, and sometimes minute, new forms of labor embedded in its very platform of choice. But perhaps the irony is not unique to activist link-sharing on Facebook, or by mailing list, or any of the mediums through which we might attempt to speak in the present day, so much of which is subject to considerable surveillance, click-mining, and digital labor, no matter how precautionary one tries to be.

Irony must also be embraced as Facebook becomes the cultural lexicon for serious political and theoretical organizing. Facebook Groups allow for the formation of critical and engaged publics through the sharing of links and the forming of definitions for patterns in the media. We might be better off focusing on the strategies of solidarity endemic to its space, recognizing the irony of the situation in which creativity and modern-day organizing often take place, than being seduced by the escapist rhetoric of dismissal.

Dorothy Howard is a writer and internet researcher based in Brooklyn, New York. @DorothyR_Howard

All right, back up a second, Merriam Webster. Have you ever bothered to consider that people might not use Facebook because.. uhm.. it sucks? Like seriously, have you used it recently? What a joke! Do you really need some weighty, privacy-minded justification for using Facebook to post and consume content? It sounds like you're engrossed by the fantasy that someone is watching you. "Surveillance, click-mining, and digital labor" – all fine subjects I've heard the EFF mention from time to time. Yes, it's right to be concerned with how much time you waste time on that stupid website. But rather than roll up your sleeves and learn HTML and make your own thing, you've instead chosen to "work within the system" and create another dumb Facebook group, add all your friends to it, and wait for the likes to roll in.

God, HTML is hard. I know, right? Let me tell you a little something about Habermas, I've wasted most of my life in school. I'm about to roll this diploma up and smoke myself out the window. Can I borrow five bucks?

And don't even talk to me about domain registration. Mom and dad were baffled when they tried to get a domain for our family. Somehow they set up email addresses for everyone, but they eventually got so much spam that they abandoned the project. Now we just use Facebook, and it's great.

Granted, I can see why you would be pessimistic. Just look at all the dumb Wikipedia clones that have existed over the years. I remember years ago there was a lot of intellectual foment around it, and granted yes it had its problems. But it's still the best place to go if you need to plagiarize for a term paper.

Did you know people used to pay for phone service? Men, women and children would gather all their dimes and line up for miles just for the privilege of talking to someone without smelling their halitosis. Fast forward two hundred years and Facebook is the biggest club on earth for lonely suckers struggling to get l-a-i-d.

Did you know people used to unionize because they were actually getting fucked over at the workplace? Read up on it! It sounds like you enjoy using Facebook for free but suspect that all is not right in Elsinore. So tell me, quick, would you die for Facebook?

"Irony must also be embraced as Facebook becomes the cultural lexicon for serious political and theoretical organizing." And how! Here's to one giant corporation controlling the "cultural lexicon" whatever that is, I think it has something to do with MTV. Did I ever tell you about the time I totally read something about the Arab Spring? We had a great conversation on Facebook about it where everyone chimed in. I'd pull it up for you, but good luck finding anything you posted three days, let alone three years ago. Hubert Selby has a great story about a union guy but it doesn't end well.

Thank you for doing such a good job illustrating the impoverishment of commenting culture outside of Facebook! You really captured the patronizing tone of a commenting demographic that feels its relevance waning in the age of social media. What were your inspirations for this pastiche?

Howard's article is a bit strange in that gives viable reasons for not Facebooking, presents some alternatives, and then concludes with the author creating a Facebook group. Pastasauce's reply also lacks a coherent purpose – what is Pastasauce mad about, exactly? Everything!

Howard's main justification for using Facebook is based on demographics ("64% of adults use Facebook, while 30% of Americans use it as their primary news source"). I would like to know more about these Pew numbers. Facebook is notorious for inflating its user data. If the 64% percent is based on polling, what is the universe – 64% of US adults? 64% of US adults with internet access? What constitutes access? A monthly phone plan? etc.

If 30% are getting their news from Facebook, does that mean 70% are still getting it from television? Maybe we should be starting our own cable access TV shows.

It's a big leap from these numbers to the statement "opting out constitutes an act of defiance of the norm." Some businesses do not allow access to Facebook during work hours for fear of company information leaking out. Is this defiance of the norm or just prudent practice? Also, how long will Facebook be "the norm"? We've been besieged by articles about the younger generation bailing out in favor of Instagram (until Facebook bought it), Twitter, Snapchat, and other venues that have nothing to do with academic non-profits. They are moving because Facebook is where their parents are.

Pastasauce's notion of sleeve-rolling and HTML-learning (if it rises to the level of a notion above hardcore trolling) is scary for many people ("what, just put up a site and wait for people to find me?") but that direction offers a hope of independence, as opposed to Howard's "learn to embrace the system" accommodation. Facebook may be a necessary step to reaching the broadest possible audience but we're talking about radical art and ideas here, not becoming a bestselling author. Aren't we? Quality of eyeballs, not the number, is what matters. The alternatives to what Ken Kesey called "the combine" are still plentiful.

Hi Tom, thanks for your comments. I looked into the Pew Research a bit more. Here is where the study is located: http://www.journalism.org/files/2013/10/topline_facebook_news_10-2013.pdf

I personally don't think independence should be constituted by who can code. That would be derived from the systematic opportunities given to some privileged members of society to acquire such knowledge required to participate in resistance.

Thanks for the Pew data – I will peruse and report back. I've been "indie" on the web for about 15 years but I don't consider myself a "coder." It's possible to host content on the web outside of Facebook without any specialized knowledge. There are many sites looking to host content, and bots crawling all of them for searchable information.

I appreciate, what I interpreted to be, the crux of Howard's point: that the public sphere has never existed in a vacuum, cut off from wider societal and economical influences, and that Facebook now resembles this sphere, for many many people as the default forum, for online discourse, in their daily life. However, something unsettles me about her acceptance of this fact and her subsequent discussion that almost came off as a defence of the Facebook platform in places.

I've heard similar, though simpler, arguments before, a "well I've invested so much time and content on Facebook, and built such a network, what am I supposed to do?!" premise. I wonder, is this not a little defeatist, cynical and, to a degree, myopic? Isn't this the same old consumer apathy so readily critiqued when exhibited in less lofty manifestations in society?

In my own, very suspect and fragile, idealism I kind of expected so much more from certain sections of society when it came to rejecting the all encompassing commercial behemoth that is FB, as the central conduit for all their intimate communications, relationships and, erm, life. I know of politically astute students, avant-garde musicians, writers, militant programmers, professional technologists, all seemingly united in their critiquing of corporate culture, and all bloody Facebook, seemingly shackled to it. However, to be fair, maybe this reality reflects shades of Howard's point too: the infrastructure we have forged for ourselves on the web is a reflection of the real world we inhabit, with all it's ideological contradictions, compromises, hypocrisy and nuances. It just seems so odd, conceding to contradiction and defeat through a compulsion so trivial as 'convenience'. If that is indeed what it is…

The discussion of nettime would have benefited from talking with the people who've been running it for the last 17 years, i.e., Felix Stalder and myself, along with several others early on. Geert and Pit haven't been actively involved in nettime since then — and it would almost certainly have fallen apart (or exploded), culturally and technically, if they'd continued. We can't know that, of course; and its durability has come at a cost — for example, it became less of a 'platform' for projects they envisoned. They deserve full credit for the their ideas and efforts early on — Geert, in particular, has been an immensely positive force connecting people around the world. Even so, there's no small irony in citing people who've spent close to twenty years accepting credit for others' work as authorities on what that work involved.

Michael, I see you have blocked my account after leaving my last comment in the moderation pile. I will attempt to respond in a way that reflects constructively on this article and the ensuing discussion.

As a way of gauging interest in this essay, I have attempted a small survey of the response on Facebook. Often we hear that the "real" discussion happens on Facebook; indeed Howard's own Facebook post glosses the article thus:

"Just published an essay where I use the example of Facebook Groups to argue that opting out of Facebook also involves a disavowal of crucial forms of vernacular culture and solidarity. Hi Facebook! I love you, despite it all.."

This short form expresses little beyond preaching to the choir, insisting that Facebook contains "crucial forms of vernacular culture" that Facebook rejects are missing out on by not being there (i.e. being elsewhere). Despite this, there is "solidarity" among Facebook users, which implies a prison mentality – we're stuck here, so let's make the best of it, "despite it all.."

By way of analogy, we can compare Howard's whole point to car culture. By "opting out" of driving, walkers and cyclists miss out on a big part of culture which is only accessible in the car. Driving is accessible to many but in practice limited by state control and enforced by police (you can't speed or drive backwards on the highway). The car is the platform – you could build your own car but who would want to (you certainly can't build your own road) - maybe the best thing you can do is learn how cars work and wind up working in a gas station. Drivers will understand the last part – the sort of solidarity we can expect at the DMV. I love driving, despite it all.

Where is the public, then? Is it in the car, or on the road? In a field of shifting signifiers, it is probably both. Public is a loaded term, and the use here is diluted somewhat since it means four different things in this article:

1) The substantive "public" in the sense of any group of people engaging in discourse, via her unanswered question "are platforms publics?" Only one platform matters here, so she's really asking "Is Facebook a public?" or "Do Facebook's users, when on Facebook, constitute a public?" Or are Facebook groups themselves a platform embedded in another platform, thus can we refer to each one as its own fractured "public"?

2) "The public sphere" from Habermas, a "historical condition" outside the privacy of the home. In a way this reduces to "going outside" and whether we can freely speak or associate there. Based on this article, the "public sphere" seems dead in the water – it is ostensibly guaranteed by democracy, but gutted in practice by bureaucracy, government, border police, etc.

3) "Public" as a publicity setting for posts on Facebook, implying it is readable to those outside the network (but not outside Facebook). I am not friends with Howard, so this post must be set to "public", meaning if you have a Facebook account you can read it (and, it seems, comment on it).

4) "Public" as a publicity setting for groups – "some Groups are public, while others require new members to be approved by an admin"… much like new commenters on Rhizome.

Oddly missing here is "public" in the sense of mutual ownership - public parks, public beaches. Any (non-incarcerated) American can go to a public park and sit on a public bench, throw their garbage in a public trash can. Foreigners, if you make it through the gauntlet of border security, customs and immigration, you too can sit on the bench beside me. Facebook provides the illusion that it is a "public" utility in this sense, since "anyone" can make an account (and, presumably "everyone" has, except for us anonymous untouchables that still skulk around on Rhizome comment threads). The Internet is public, but individual access is usually private (unless you, poor soul, are using that grotty Dell at the library).

"Be wary - the Internet is still a dangerous place! The raw, public Internet is full of thieves, you can't trust anything, even email." This is the vibe we get from the comment on Rhizome's Facebook "post" for this article. The commenter did not see this post on Facebook first, but on an email update from Rhizome. Michael Connor is quick to reply, begging her to click "trust" since this will help future emails navigate through Google's spam filters. "Dorothy's writing style must be similar to scammers," he quips. No further discussion here, nor on any of the 13 shares.

Howard gets some more traction on her own Facebook post, again public. Three people comment. One is a short message of support ("luv this") akin to a verbalized "like" (incidentally, "Dorothy likes this"). The second is weirdly – hopeful? I can't say. Apropos of nothing, the user "Soap Bar" insists "fb II will start up eventually" but laments "corporate control will never die only be sidestepped avoided and ignored". Not clear if Soap Bar actually read the article, since via Howard's border security analogy, a system of control cannot be ignored for long. Soap Bar will be caught by the "real name" policy eventually.

Finally, we have the pithy comment from Brenda Starr: "Who opts out of Facebook? … Exactly." Again unclear if she read the article, but the implication is people not on Facebook are not to be trusted. I'm reminded of that quote from Groucho Marx about clubs and members. Get with the program, Groucho!

Howard's repost on the "Cool Freaks Wikipedia Club" page received one comment that hits home, from one E.J. Boulton:

"this is actually super helpful cos i've been trying to mention CFWC in a PhD proposal document (which is Deleuzian in theory) - citing an article from a journal called 'Rhizome' is pretty perfect"

It goes without saying that by supporting this sort of pro-Facebook, anti-Internet discourse, Rhizome legitimizes it in a way that can only be appreciated by a PhD candidate. The legitimacy here stems not from Rhizome as an arts institution or a cultural organization, but from the name as a mere pun – which I cannot appreciate, since unlike these over-educated ironists, I've never read Deleuze.

Taking these posts and comments into consideration, we must ask the question – does "discourse" on Facebook ever rise above phatic communication? That is, is anything actually communicated beyond pleasant chit-chat? Beyond dumb jokes, beyond saying "me too". Is serious thought appreciated, or merely "liked" or dismissed with an ironic "ayyy lmao". Does the level of non-phatic communication ever rise above questions about Mom's Gmail?

Judging from a longform post on Howard's own group, we must answer with an emphatic *yes!* Far too long to be pasted here, we have a multi-comment rant from one Eric Reilly. Little is revealed about Eric from his Facebook, beyond his residence in the Bronx. He has a blog - http://thecentralcommittee.blogspot.com/ - where he posts similar long-form essays. I don't really know what to say about this guy, except that I've encountered similar individuals on the (shudder) Internet before, who seem to type until their fingers fall off in an ecstasy of blather. The term "pant load" comes to mind.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/immaterial.labor/permalink/1647413242139605/

I'll quote the first paragraph, but you should really read it all:

"agree with the predominant argument along the lines used by those who oppose 'developmental' economics for 'opting out' of the global market - to be in the global market creates pressures to peripheral nations, but to cut its production off completely would only make the dependency felt more"

Again, we must ask: did this person even read the essay? Dorothy Hexa Howard seems to think so, as she "liked" his first comment – but not the other two. Being a bit judicious with your likes, Dorothy. Aren't you taking this a little seriously? The lack of response from Howard, either here on any of these Facebook comment threads, suggests she isn't really in it for dialogue either – maybe only a bit of institutional "cred" from posting (not commenting) on Rhizome.

Not sure I would want to talk to any of these people, either. Perhaps things really are better on the private powder rooms of closed FB groups, though I imagine it's really more of the same (combined with a dash of moral condemnation, perhaps). Thus I find my terrible thesis reaffirmed – opt out or no, real discourse is not happening on Facebook. I look forward to more Rhizome articles in praise of the decay, imbecility, and tastelessness endemic to Facebook.

Here is just one public-facing thread on Facebook (that I've highlighted on this very site before) that rises above "chit-chat" about "mom's gmail" (ugh at the phrasing and innuendo):

https://facebook.com/micol.hebron/posts/10152847041920752

Your examples of the "missing" sense of the term public are all spaces. A more apt analogy for Facebook would be a public utility. Public utilities can be privately owned or publicly owned, they are not necessarily characterized by "mutual ownership" - only by public oversight. And such oversight is only likely to emerge through the organization of users themselves, very possibly with the platform itself as an organizing tool.

"Pastasauce" has a reply to Michael Connor – I was emailed a copy – and no, I am not Pastasauce but I certainly sympathize. Pastasauce has apparently been "blocked" and cannot post the reply. Can this be remedied? I strongly disagree with Michael Connor's implication that "commenting culture" is richer inside Facebook than outside. Pastasauce's reply examines some of the Facebook comments made in response to Dorothy Howard and they aren't very rich. I think Rhizome readers should see this. Please let me know here if Pastasauce is unblocked and I'll get word to him or her. If it looks like he or she is banned, I'll post the reply on tommoody.us.

No one was blocked. (Though we didn't let through one comment from Pastasauce that failed to meet our commenting policy: "Content may not include any material that defames any person," which this one did.) The new comment, along with one from Dorothy on the Pew data, was stuck in moderation because I was away for a long weekend. :-) They're both public now.

Pastasauce's comments are mean and sarcastic but the analysis of, among other things, the different notions of "public" are well worth considering. This confusion over what's public came up during the recent Ryder Ripps controversies. Paddy Johnson took screen shots of Ripps' Facebook conversations (which she, but not everyone had access to) and made them the basis of a critical "hit piece." When called on this, she said "Ripps has a public Facebook presence." What does that mean? I can't view his content. To me, "public" means viewable without a login and fully searchable. I realize it's awkward for Rhizome staffers and writers who spend much time Facebooking to have legacy readers that still believe in an open web environment. Pastasauce compares Facebook to driving, with its accepted rules and regs, but to me the pro-Facebook articles by intellectuals sound like jokes pack-a-day smokers make to each other: "Yeah it's taking years off my life, but they're the years at the very end, and who cares about those? Heh heh heh."

It is a mistake to rely too much on what is technically public or private to guide decision-making about whether to respect the contextual integrity of any communication. Hilary Clinton's emails as Secretary of State are technically private, but have no legitimate claim to remaining so. Many Facebook users might accidentally set posts to "public," without intending for them to be shared widely. And even users on the very public Twitter have felt violated, and perhaps rightfully so, when their posts were shared onto other platforms.

Another term I like, since public and private get quite fuzzy, is "contextual integrity," as articulated by Nissenbaum. The idea there is that communication is often intended for a specific context, and when it remains only in that context, then it has integrity. When it is moved to a different context, that integrity has been violated.

A blog posting a screenshot of an artist's Facebook post would certainly be a violation of the artist's contextual integrity–but that doesn't mean it's always indefensible. There might be a strong public interest argument to share the post, and blogs have a responsibility to their publics which might outweigh this consideration. If an artist uses social media as part of the publicity surrounding a work, that might even be crucial for understanding the work, then that also could make it more OK to share.

These questions are very important for our current dynamic web archiving efforts…very tricky stuff.

If you have a substantial time investment in Facebook and put a lot of content up there, you might want to think of it as a public utility. I believe the web is large enough for people to have a public presence without being on Facebook, and this "utility" is sand you're building your castles on. If you're stuck in the sandlot and want to organize with your fellow castle owners to make the ground less toxic, fine, but I'll always think it's kind of silly.

Another problem with the public utility analogy is that those entities are government-granted monopolies and are subject to public oversight. If you have a problem with the power company you have a government board that hears your complaints. Pressure comes from without, not within. Whereas Facebook is this weird voluntary addictive thing that takes over people's lives and most of them don't know how they got there (to continue the smoking analogy). We try to offer those people alternatives, we don't encourage them to organize as they continue to buy tobacco.

More on the "contextual integrity" issue in another comment.

I found this useful, thanks.

I guess to add to this is the fact that a Facebook users participation with the service, and their intellectual property creation on it, directly contributes to Facebook's revenue:

http://qz.com/335473/heres-how-much-money-you-made-for-facebook-last-year/

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/01/29/facebook-quarterly-earnings-q4-2014_n_6568712.html

Doesn't this too make any comparisons of FB with public utilities problematic?

Not really - but I'm using the term public utility in the usual sense of a body that provides something like water or gas to the public, but may be privately or publicly owned. (A NYC example: Con Ed).

If we're talking about publicly owned utilities, then yes, that is something different. I am really interested in the idea of software as publicly owned utility–this is something that was discussed at our recent event with Airbnb Pavilion.

It would be great to see more sharing "economy platforms" run as public utilities, since those often have a very direct economic impact on a city. My sense is that Facebook would be kind of a poor use case for public ownership - but it is interesting to think of as a public utility in the sense of a private company that provides public infrastructure & service and therefore has some level of public accountability.

In the case of Paddy Johnson's unpermitted use of Ryder Ripps' Facebook screenshots, there was no "strong public interest argument" to share the posts. His art was not made with public money. It was mostly lazy art criticism on her part. His "Art Whore" piece as documented on Livejournal was difficult to attack on its own terms so she relied on a private argument he had with an emotional Facebook commenter to provide extraneous text that undermined his project. (I'm saying Paddy but it was her subordinate Whitney Kimball.)

Artists violate contextual integrity all the time. We ask a bit more from our record keepers.

The other consideration I raised was whether the profile was being used for publicity purposes. The larger point there is that not all contexts are created equal, and so violating their integrity can be more or less justifiable.

Again, not commenting on the specific situation but rather the general case: there is a difference between communication that takes place via a profile that is only shared with close friends and the communication that takes place via a profile that is shared with journalists and used for publicity purposes. In the latter case, the contextual integrity violation could be much easier to justify even if the public interest case is relatively weak.

Why do you qualify the the facebook commenter as emotional and not Ripps himself?

They may both have been emotional. My point was the Facebook argument was "secondary" information and the Livejournal documentation was the "primary" artwork. This also applies to whether Ripps was using the Facebook account for publicity.

A good art critic reviews, say, a painting. A bad or lazy one reviews the press release or artist interview, that is, "attacks the hype." A more scholarly approach to writing is to consult secondary sources only when the primary are ambiguous or incomplete.

Also, Ripps has said here on Rhizome that "the comment thread was friends only and i did not expect excerpts that fit the [AFC writer's] narrative to be screengrabbed." This was not a case where the post was "shared with journalists and used for publicity purposes."

Relevant to this post, the New Inquiry published a short reflection by Teju Cole, that had originally appeared as a Facebook post on the writer's personal page, about NY Mag's cover story featuring 35 women testifying to Bill Cosby's history of rape and assault.

Cole's original FB post: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=10153087620542199&id=200401352198

Tumblr version of NY Mag story that Cole had linked to (at the time, the NY Mag website had been taken offline by a distributed denial-of-service attack): http://nymag.tumblr.com/post/125179609945/im-no-longer-afraid-35-women-tell-their

TNI repost: http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/dtake/improving-on-silence/

From Cole's intro: "I should say that this note was first written for my Facebook page, on July 27 2015, and I think it will retain some of the tone of that context: discursive, reactive, and addressed directly to my followers. But my editor at the New Inquiry thought I should share it here, with a broader audience, and I agree."

Perhaps the piece will circulate more widely on TNI; it will circulate differently, for sure. I'm still not sure what "independent" means, but on one count—the writing standing alone rather than within the feed with prominent attachment—its "independence" on TNI is perhaps detrimental in that it competes with the NY Mag story. (Cole acknowledges this in his intro.) The comments on the original post (ranging from simple thank yous, to lengthy responses, to, as across the web, gross parsing) are immediate and interesting, and they won't run on TNI.

In any event, it's a piece of what I think is meaningful, critical writing instigated by Facebook, with a tone and position resulting from the social media giant's culture, and the publics it can gather.

Yes, intriguing. Generally though, shouldn't this morphing of traditional publishing mechanisms, facilitated by FB, cause us to pause for further thought.

This Columbia Journalist Review opinion piece from April,

http://www.cjr.org/criticism/facebook_news_censorship.php

nicely conveys some valid concerns (and provides a intriguing crop of supporting links to boot).

Points of note:

• Two-tiered content sharing system; those who can, pay more to ensure better exposure

• FB's competition acquisitions and their potential for monopolising internet sharing

• FB's investment in lobbying

the difficulties an organisation faces when wielding excessive dominance and unbridled power

Nothing new here you may add, but I'm still struggling with the general apathy to these issues (and the others discussed) among the more digitally literate and cyber cultured. It's not a criticism as such, I'm just trying to define why that is.

I've looked at Dorothy Howard's Pew polling numbers. There are more recent surveys than the 2013 one, although the results are similar.

On social media use generally: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/01/SurveyQuestions.pdf

On where internet users get news: http://www.journalism.org/files/2015/07/Twitter-and-News-Survey-Topline-FINAL1.pdf

The survey universe is pretty small. 2000 US adults were interviewed; half of those were via cell phone. 75% of those adults self-identify as internet users. The percentage of US adults (adjusted for internet use) who use FB is 71%, which seems high, but of those only 45% visit several times a day. A significant percentage uses sites other than, or in addition to, FB: Twitter (23%); Instagram (26%); Pinterest (28%); LinkedIn (28%), with smaller numbers visiting those sites several times a day.

As for where users get their news, 40% of Twitter users say Twitter is "an important way I get my news" and the same percentage was found for FB users.

This may be a compelling argument to be connected to *some* form of social media but I don't see why it has to be Facebook, especially given all the negatives ZI is reminding us of. Howard's lead statement, "Facebook is so widely used that opting out constitutes an act of defiance of the norm," is essentially an advertisement for Facebook and is thinly supported statistically. Again, I realize we have some heavy Facebook users on the Rhizome staff but I don't think it's fair to couch this as a popular mandate or say that Facebook rises to the level of a "public utility," the way the telephone system was 40 years ago. There are too many other options: you should be emphasizing those.

I am actually thinking about the same subject for a while now. As a social networking tool I disagree with the initial structures of facebook.

I do think it is ego-centralized, not subject-centralized which at first made me conclude that people couldn't form organic groups just by common interests - like in specific politics subjects, for example. It is a fact that facebook doesn't at first try to create new connections in between persons who didn't have a connection prior to the online world. It just tries to reproduce the social connections already made by the user - almost, in my opinion, a documentation of the 'real' (read here: offline) social connections of people - kind of alarming in terms of surveillance. Before, facebook had a slogan which would say "connecting people around the world" - I don't have the exact phrase anymore, correct me if I'm wrong - which they later changed to "Connect with friends and the

world around you on Facebook." (much more honest for the purposes of this social media tool). I am not even touching the surface of facebook being used as a social net tool, because there are SERIOUS ones.

That's why it was a surprise for me when I first saw feminists groups and groups of empowerment of women in arts (giving an example from my own perspective). As did some other women, surprised by the amount of girls 'in activity' throughout the internet. In this story, Laura Lanne says "I noticed when I was a teenager that I only knew comic books made by men. In the Internet I found a lot, but not in the magazine stores and comic fairs - Wow, they’re a lot! Was it a secret? There’s a gap in between the number of women making comics and the attention they get."

http://ladyscomics.com.br/zine-xxx

And the fact is if you look for groups of women in comics on facebook you will encounter huge communities. You will find more publications made by women than you ever found in the main mediums of publication. Another good example is 'Retórica Clitórica Corpo em Festa', a zine produced by Drunken Butterfly. They made a public call for women in arts to create one page about feminine's sexuality. They made it mostly through facebook groups and out of it they created a beautiful publication that raises feminine voices to a broader public.

http://issuu.com/drunkenbutterfly/docs/ret__rica_clit__rica_-_corpo_em_fes/1

I do think the other alternatives for communities and discussions and social networking in general should continue to raise and be created, and I could never get tired of the attempts, if the tool we're using doesn't serve our users in the best, nothing more natural then the emerging of improved solutions. Still I agree that using the facebook groups for political engagement generally strengthens the causes.

So opting out of facebook, I agree, is probably not the best alternative but still, people should never stop engaging in the same topics outside of it. Maybe even use the existing groups - or create groups - to get people out of facebook into different communities - I've seen it happening in the case of women in arts.