Rhizome is accepting proposals for its $500 microgrants until July 23. Here, one of last year's awardees shares her experience.

You can tell that my hired hacker is good at computers by his effective use of Photoshop's Neon Glow filter.

To be an artist in New York is to be a brand, or at least it is if you have any hope of achieving whatever your metric for success is. (Unless your metric for success is the pure self-fulfillment that comes from creation and intellectual exploration.) I am a terrible brand; my pursuits are as scattered as my online identities, and my Klout score is currently a meager 44.11 thanks to my lackluster Twitter and Instagram offerings. To solve at least one of these problems, I submitted a proposal to Rhizome's microgrant open call for web-based projects last year in the hope of using the award money to hire a hacker to secure two abandoned accounts on Twitter and Tumblr sharing the username "everyoneisugly," a brand I have been trying to get on lock since I bought everyoneisugly.com in 2011 on a whim because I was surprised that the URL was available. I make a living as a developer and have been goofing around online for over twelve years, but my knowledge of the deep web (here I use the term to describe the hidden-but-public networks that can only be accessed via special configurations or software like TOR, although pedants insist that it has something to do with the early 2000s) was limited to a cursory understanding of encryption and an assumption of criminality. I was bluffing, I was a finalist, and I decided I had better start filling in the gaps in my knowledge. I quickly discovered that the deep web is as much of a parade of clumsily manicured personas as any comment thread on a popular art world Instagram.

With my soul I have desired this dead account for about 4 years.

I've been coding since I made my first "Which Weasley are You?" online quiz in middle school, so how hard could this be? I signed up for a secure communications workshop hosted by Thoughtworks, just to play it safe, and diligently wrote down the email address of the ACLU representative present, for when I inevitably ended up on a watchlist or in court for having the audacity to hack the planet. I set up a burner laptop with Tor (could never get a virtual machine to work), and kept a little notebook with all the passwords and mnemonics for all my new deep web accounts. I finally finished reading Bleeding Edge; I bleached my hair. I was ready to go.

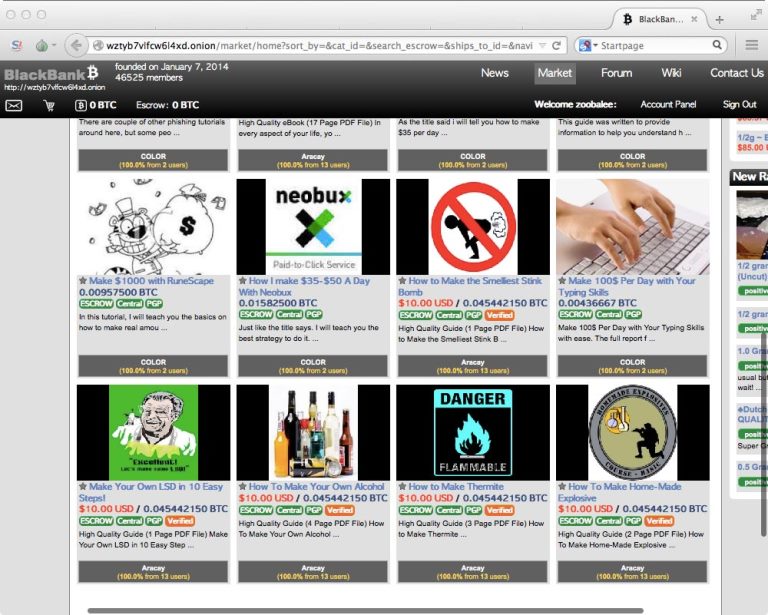

The deep web is above all else the sort of he-man women haters club that puts the greatest warriors of Gamergate to shame; its users idly post vile images and threats without fearing the consequences. But if everyone is anonymous, no one is actually doing any doxxing, and the whole pissing contest is underscored by how difficult it is to hire anyone to do anything truly illegal. The markets are flooded with bogus listings guaranteeing to teach you how to hack anything, or how to be better at oral sex, or how to make $1000 working from home, and the forums are similarly full of real or emotional teenagers begging for a cracked login to Pornhub. I couldn't find anyone prepared to hack Twitter for me, but I did find someone trading Pokémon cards for bitcoin.

Like all deep web markets, BlackBank caters to the deepest needs of your average 14-year-old boy.

I kept hitting dead ends, and couldn't even find anyone who knew how to send and receive encrypted emails. Even when I contacted firms whose logo featured Comic Sans and a logo made in MSPaint in '02 (surely an indication that a business is too successful to fail due to marketing), I couldn't find a single hacker or service with any sort of positive reputation.

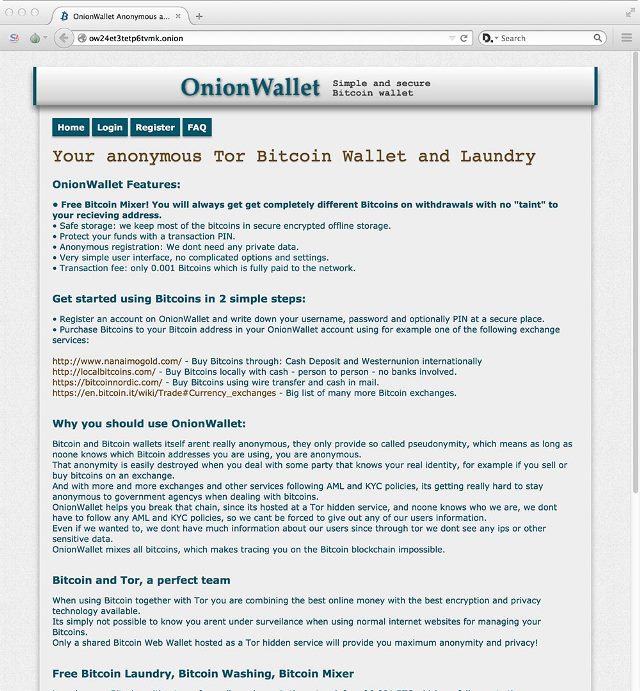

Before I knew it, I was well past my 4 month deadline for the grant with nothing to show for it. I began to exchange the money for bitcoin at least to be prepared to pay someone when I found them—a painfully slow and paranoid process of moving the money though increasingly unreliable services. I told friends there was no way anyone would prosecute me for the project, it was so clearly satire, yet I still lost sleep worrying that someone would care enough to take legal action. I was preemptively mortified at the thought of jail time for an art joke. And yet I was still too lazy at least to meet someone in Jersey to buy untraced bitcoin with cash. I went with the only online service that wasn't a mess of dead links, and when I finally lost the money in the sort of exit scam now well known in the mainstream web thanks to the fall of Evolution and other markets, it was a relief. I had $16 left of the original $500 grant and none of the anxiety of searching or the inescapable gloom of seeing so many people pathetically trying to scam each other.

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.

I decided to backtrack and mine my experience for other content, which lead me to a British comedian who was unwittingly advertising scamware. If you Google "how to hack twitter," there are plenty of mainstream web solutions. You're advised to report squatters to Twitter, which doesn't work. You can try and hire someone through Fiverr or Hackers List, who will probably return your $5 after you tell them that a PDF about how to root a server isn't what you asked for.

Hackers-for-hire on Fiverr typically offer to teach you how to do your own dirty work "for educational purposes."

Or you can dig around through the piles of instructional videos showing you how to do the job yourself. DailyMotion, a throwback to YouTube's golden days, is full of these, and I stumbled upon what I thought was an obvious satire of the genre:

But clearly, it was not obvious enough. Several scamware sites use the video as promotional material, and the comments for it include wannabe hackers asking for advice or begging to hire the creator. It was easier to track down Michael Spicer, the comedian responsible, than it was to dig up any information on my account squatters. "If it's on the internet, there will always be people falling for it. And if scammers want to use my videos, well then, knock yourself out," said Spicer in an interview I conducted in February, about a week after I had lost the money and given up the cause. "Whenever I got these begging tweets from young people, desperate to hack into their friends' accounts, all I felt was pity. Many teenagers these days are drowning in the digital world. When I was young, falling out with a friend didn't get as ugly as it does now. The Internet is a terrifying weapon in the hands of an aggrieved teenager."

The scammers using Spicer's video as advertisement market themselves to the forgetful user, not only the vengeful one.

"Peter," who I first contacted via one of the many forums I scoured, may be such a teenager, although I don't know how old he is. He was responding to someone else's plea for a Twitter hack, saying he knew how to make that kind of thing happen. I tried to encrypt our conversation, but he was one of the many self-styled hackers I encountered on the deep web who didn't know how to use PGP, which should have been a tip-off at the outset. Nevertheless, I enlisted his help. This was the moment of my greatest anxiety: I would have to reveal my identity to my hired hacker in order to finish the job. A simple Google search of "everyoneisugly" brings up my own website, Instagram, and several other accounts in addition to the two I am trying to acquire. It also brings up the Rhizome announcement of my intention to do the project in the first place. Could I trust Peter to preserve my secrecy and understand that he was only to go after the Twitter and Tumblr accounts with the username? Probably not, but what did I have to lose at that point? Would he be offended by my treating the noble art of hacking as an inside joke for artists? Well, too late. I told him I had a budget, but when the money was stolen I just fell out of touch with him, since it didn't seem to be going anywhere regardless.

After a short hiatus, Peter reached out to me via two different email accounts to try and phish me in order to sell my own clear web accounts back to my deep web self. Some l33t sk1llz for sure. I wanted to think he was maybe exacting revenge on me for flaking on our deal, but I honestly believe he was just confused. Both email accounts he used were easily traceable to his real name, his location, and multiple online profiles. I still don't know who owns @everyoneisugly, but I know where Peter lives, that he's pro-gun, and that he likes to stalk gymnast Shawn Johnson on her Flickr. I know that he's the kind of guy who makes his Google+ profile pic an Anonymous logo and then comments on hacker instructional videos asking for more help with cracking WEP keys. I changed my passwords, but I don't know that I needed to bother. I told Peter off for being stupid, but, to be fair, it's not as if I was any better.

I still have the $16 and have, nearly a year later, looped back to my original strategy of griping to friends who know people working at Twitter in the hope that someone will just nuke the dead account and let me have it. "Hacking Twitter" amounts to phishing, and if there's no one to phish on a dead account, you're out of luck. I still dream that some clue will surface, or that someone will respond to my multiple offers to buy the accounts. Despite threats and stories about this online haven for assassins, I found navigating the deep web to be as innocuous, tedious, and fruitless as trying to schmooze at an art opening in the hopes that someone, anyone, will actually show up for a studio visit.

I could have bought so many followers with that money. But mostly I just want to move on. I'd really rather be painting.