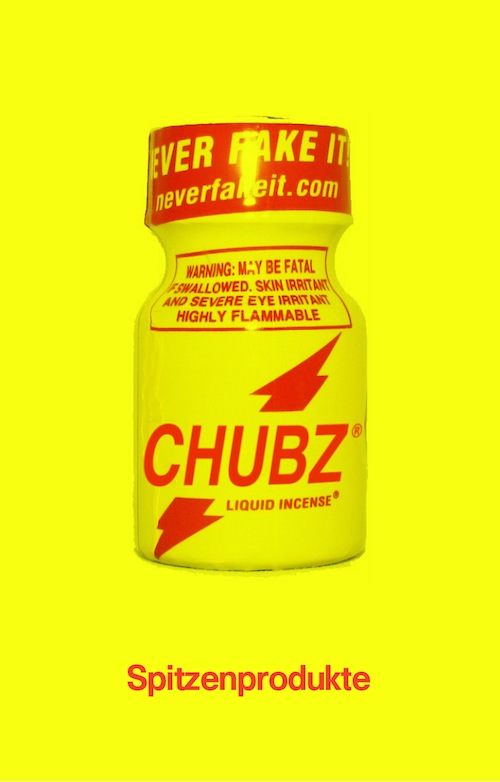

Chubz: the Demonization of my Working Arse is the first book by Huw Lemmey (aka Spitzenprodukte)—a work of fanfiction inspired by young Labour party member, author, and Guardian columnist Owen Jones. First person accounts of protagonist Chubz' hookups with Jones are interspersed with depressingly funny episodes recounting UKIP leader Nigel Farage's poppers-fuelled campaign. Sex and politics—contemporary cruising, self-representation, and brand identification—have underpinned the majority of Lemmey's work prior to Chubz, including "Digital Dark Spaces" and "Devastation in Meatspace" (both The New Inquiry). A book launch for Chubz was held recently at Jupiter Woods, London (October 28), featuring readings from the book and from earlier material, including a poem by Timothy Thornton (found here as two PDFs). I spoke with Lemmey about his book in person and over email. The book can be purchased here.

LH: Over what period have you been writing Chubz, and what motivated you to use the mode of fanfiction to develop concerns about sex and politics that you'd previously expressed in journalistic fashion?

HL: I don't know when I started; I left London for a summer in 2012, during the Olympics, to live in Dublin. I guess when I was there I started putting down some ideas for what the book was going to become, but I was very much writing some sort of speculative futurist thing, trying to think about the city through a language of future branding. It felt very strange being out of the country that summer. I was sure the place would try to erupt like the year before, and worried about how that would play out given that there were literally soldiers on the street when I left in June. When I got back that autumn, and there weren't more riots, I was surprised, and now there's this point at the end of every summer where I'm still surprised they haven't happened.

It is certainly a book related to a lot of my earlier writing; it's about twin territories, an online social space and the city, and about how the two overlap, which is a preoccupation of mine. In this case it's Grindr, it's about how you can use Grindr to read the city and the city to read Grindr. They're two territories superimposed on each other, a digital augmentation of reality. I started writing fiction about it because the tools at my disposal for non-fiction just weren't sufficient, or I wasn't good enough at it. The way people use hook-up apps is too subjective, and I felt like the only way I could talk about it honestly was to talk about it partially, in both senses of the word. I talk to a lot of guys about how they use Grindr. I like to go for long walks through the city with people and it normally takes about an hour before guys stop talking about the things everyone talks about—the overt racism and homophobia, the aspects of timewasting and wanking and stuff—and start admitting to sometimes thinking quite deeply about how the whole process from download to hook-up affects the way they live in the city, and how they construct their own sexual desire within that.

As for the fanfiction; well I think Owen Jones as a public persona is kinda an interesting avatar. To be honest, he's completely instrumentalised in the book, devoid of real agency as a character, and totally 2-D. But his book [Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class (Verso, 2012)], and the way he has produced himself as a public figure from the publicity surrounding it, is for me a really interesting hook to talk about the disconnect between class, sex, and politics as a Question Time debate, and as lived experience in streets and shops and bedrooms. That's the worst thing about public gay identity today; it's total fucking Ken-doll sexuality, reasserting categories for behaviour and binaries, full of these aspirations for acceptance and assimilation with men like Sam Smith banging on about husbands and puppies. It's boring and gross and violent.

Chapter 3, 20-21:

I'd done two hours overtime; my boss was acting the cunt all afternoon

– you do realise this is the sort of thing that's linked to your bonus Andrew

– I know and

– And I'll be writing your 6 month appraisal soon. Look I know it's a pain Andy, really, but it'd be really helpful if you could

Alright alright; two hours later, no pay guaranteed, I'm sick of this job already and I push my face against the window and feel the warm vibrations of the glass and the girls in front talking who each other are fucking. We stop at lights; days like this make me dizzy, my eyes too hot, tired and in need of instant response.

My smartphone needs to be squeezed from my pockets, and I swipe through my social networks. I load Grindr, ping through my messages; no, no, would suck but no, I load the feed, a mosaic of torsos; one wears a t-shirt and I can see a dark fleck I take for nipple through the white cotton. Lips are visible, just and a blue box appears in the corner. A message from the boy; this is how I met him, early in that summer heat, face worn out from work, beads of sweat meeting in my lower back. His name was Owen, and he sent me a facepic; cute, boyish, blonde hair surfing over delicious blue eyes.

LH: Why did you decide that the Grindr profile encountered by Chubz should coincide with the official portrait the public are likely conjure when they think of Owen Jones? I also wondered if your references ("field of blue checks" (61)) to the shirt Jones wears in his press image are intended to reinforce the reader's perception of him as an establishment "straight acting" figure, or moreover to associate him with the grid of Grindr's homepage.

HL: I guess because I think one of the key themes of the book is about men with opinions. Men, and specifically white straight men, have this role within the mainstream of comment journalism which allows them to be almost disembodied with their opinions; they serve as an avatar of a political position, whether it's the muscular liberalism of men like Rod Liddle or Brendan O'Neill, the compassionate conservatism of Peter Oborne, the soft left liberalism of Dorian Lynskey and so on. But their position within society means they never have to perform their subjectivity in order to get that voice, in the way many women and trans journalists (who are often much sharper political and cultural brains) do. And I think Owen Jones fills a really interesting position on that spectrum, as an openly gay socialist, where he has to be clear and open in referring to his identity as a gay man without ever having to dip into deeper subjective reflection of his desires and desirability in print. I think the constant insistence that women have to recount themselves through this personal, subjective lens is a really abusive tool of dominance and control, so I can well understand why he steers away from it, but as the basis of a character for a novel I think it's really rich precisely because it's a public sexual image itself, totally disembodied. It's about removing sexual politics from being about the interaction of fleshy, meaty bodies contesting spaces and identities and manifest in both joyful and traumatising physicality, and making it this private, bourgeois politics of rights and contracts.

It's Jones' public avatar that's used here, because I don't know anything about him as a person. My interest is to put the flesh and fluid back into that avatar, but what better place to start than a literal avatar as the object of fantasy.

Chapter 6, 70-72.

I try to talk to him, but he's gone now, to a better place; blood is returning to his face, and his stoned eyes flicker with comprehension. I bite my lip, I love the sleaze. He smiles at me, and in that moment I know he trusts me, he trusts my ass. It could do anything to him, anything at all, he's convinced. He smiles, and I smile, and he does it, he fucking does it, he forces his head between my legs. His hair bristles against my buttcheeks but there is no pain. Just pleasure, as my butt gulps him in, and I rock forwards and back, the greatest power bottom ever bred, a prizewinner, a destroyer of the penis.

The noise of the train is quieting, my butt is finishing the job, and within minutes he is pulled deep inside me, ingested, brewed, stewed by my ass till all that is left is his trousers trailing from my arsehole, his black socks coiled lifeless like used rubbers on the floor. I pant and breathe in victory, so proud of my heroic butthole. It plans its conquest. If I had my way it'd never stop. I'd let my anal juices, that seem to make my insides so desirable to all these ball havers, these swinging-totem poles, these bureaucrats and these penised shitehawks who insist on mouthbreathing round the city like little princes, I'd let my anal juices digest his skin and bones and all this fleshy matter like a flytrap, like a serpent. And now I've ingested Owen I don't want it to stop, I'd move onto the next man with my siren's buttocks, and one by one I'd suck them in and chew them up till one by one I'd hovered them all into my ever more muscular rectal cavity and before I'd realized I've destroyed the male sex, destroyed them all, in their entirety, one by one, every man who writes and speaks and passes laws and checks documents and has an opinion, and I'd let this hot acidic anal syrup digest me from the insides and eat me up too so that no man survives, no more men, even myself, one by one, just to make sure.

LH: In comparison with Nigel Farage, who appears in humorous episodes between Grindr hookups, and the abhorrent dad of Chapter 12, Jones is really very progressive. Sex with him leads Chubz to fantasize the destruction of all men, however. What is it about Jones that made him the ideal victim of symbolic sacrifice in your book?

HL: Well I think maybe there you're implying that the anal feasting is somehow an act of sexual-political violence? I couldn't disagree more; Jones' consumption by Chubz' rectum isn't some sort of punishment, it's a generous act of gift-giving, not symbolic sacrifice but the symbolic welcoming in to a corporeal community, isn't it? I suppose that's a matter of interpretation but I think the tension between the physical and the avatar is a tension that is the only thing that humanises the Jones' characters completely dull and uninteresting identity on the page. Orgasm is a moment of transference, a ceding of masculine power...

But in many ways Jones is supposed to be dull here; what's really interesting about IRL Owen Jones' interactions with those who claim a more radical position than him is his constant willingness to engage with them, which speaks volumes about his political project as I think he sees it, one of bringing together various different political positions into a cohesive leftist challenge to a dominantly right-wing or liberal media environment. I don't think he gets enough credit for that position, to be honest, and I think a lot of people to the left of him do him a disservice by not at least tacitly acknowledging that that's his political project. That's not to say their criticisms of him are often not very valid though; the point is the tension doesn't come through the different political positions but through the different attitudes towards communicating that politics. He's been proved right about that strategy, to a certain extent; there's definitely a gap in the public discourse for a reasonably traditional, stout socialist position. But whether that reflects on political change is something very different.

So then part of the subtext of the book is really about watching this public battle played out online between these two groups, two strategies of public acceptability, engaging on the terms of public argument, or more vicious, lived experience, the practice of a sort of online witness to the obscene inhumanities and fucking snowballing injustices of the UK today. I'm horribly indecisive but coming down on the side that what's actually important is making the real, visceral cruelties of the moment legible, and even unavoidable, and highlighting the complete lack of options, the dissolution of hope in any sort of socialist redemption.

Chapter 8, 89-91

In my mind I make a composite of Faron from the photos on his profile. How his head fits his body, how the skin from one photo, distorted through a dirty mirror, blends with the skin on his torso, bleached dry from the flash and the low voltage lighting of the gym shower rooms. He's a collage of iPhone shots, a frankenstein top I'm piecing together from bits of grindr and second-hand sensations.

(…)

Whatever happens, he cannot know how much I would give to take that drop of him alive on my tongue. I'm a different boy online, I write out his fantasies, what he needs to hear to bring me over. This is how I live. I project in type the form he needs me to take. Each bright red message betrays a new falsehood to him.

I get a particular thrill from sex organized online. I measure the hookups in data involved, uploaded or downloaded. I can trace the development of our social tension and sexual thrill through datestamps, and I can count them in bytes. I have never heard this man's voice. I have never seen his flesh bristle and twitch; every hint, insinuation, every targeted pause, I can account for as data. I never do. I never run the analysis. Quantifying is not the thrill. Disembodiment is the thrill, mediation, running desire through culture. Description, narrative. His hands are coded to his body, his body coded into flesh as the front door peels open.

LH: Can you talk more about the ideas of disembodiment and writing desire expressed in the above extract, as well as in the final pages, where these ideas are framed politically? (For example: "my strategy is bodily love," "The breakdown of security for the rich and powerful in London was tied so closely to our feet and legs and chests and arseholes I could only marvel" (177), "we used [our bodies] together like a diagram, a diagram of a process all linked, how my body worked with the body of the boy I'm next to—that became our politics because that's where power was." (178)).

Though in Chubz these themes are approached from a gay perspective, they resonate with the text read at the launch by Aimee Heinemann, who entertains a moment beyond orientation, gender and even the category of human, also facilitated by the internet:

In the future nobody will ask ASL, we will ask AVM—animal, vegetable, or mineral? Spit-and-sawdust internet cafe, the beings who have decided not to be people, linguistic post-humanism, the revolutionary potential of the intersex friendly ghost, chaotic good dragon kin, deaf transatlantic mermaid, ALL GODS NO MASTERS, the post body is the most body, be a dragon and a queen. (via)

HL: I don't know. I can't speak for Aimee. But speaking for myself, my body and the bodies of lovers is not something I've begun to come to terms with. I've never felt forced to encounter my own body like I think a lot of people, especially women, are. You can just ride around in it at as a bloke. So it's only begun as a conscious process since I started to acknowledge that. And it's much easier to come to terms with bodies through mediation because there's just so much access to mediated bodies. I do dream in drop-down UIs. I do feed upon the pornographic image as a building block of my own desires. I do think the iPhone is the country's most popular sexual prosthesis. I can't theorise beyond my immediate feelings about this any more than to say that communist politics is always, has always been and will always be a politics of bodies; of the mass worker, of the body at work, of the abject body, of bodies as tools and of the utopian ideal of the body as ours to decide. And I remain a communist, albeit one unable to coherently express a single practical political vision other than that we must get there through some sort of process of bodily self-direction.

Postscript, 182-183.

You can't forget the panic of consummation, the burning streets, the 1000 ski masks with fat penises where the eyes of the loser militia should be.

The key to a happy, healthy life and sense of wellbeing is ensuring an intelligent relationship with your key life-brands. Keep your personal portfolio of brands fresh and balanced.

The feeling of being part of a mob bears little relation to its representation. At least, that's my experience. If you want to feel like an individual who has importance, join a mob. I enjoy situations of civil disorder because I enjoy watching people trying to kill each other.

The looter and the online pirate are the subjectivities with the clearest, most intuitive comprehension of the nature of contemporary semio-capitalism; they are the brand ambassadors, and if they cannot be harnessed they will overrun and destroy it. A strategy must be had for disempowering and utilising us: and it cannot be legislative.

(...)

The strains and insults incurred through the day, the working day, that are pushed between the two of us. We can rework the social tensions of him, the white-collar yuppy, the buy-to-let landlord, the ethicist in the supermarket aisle, the profiteer and the privateer, the bastard, the nice guy, Mr Nice Guy, the nice guy who means well, and me, the 6-month let, 6-month contract, managed and manager—we can rework those tensions between thumb and forefinger when we peel off clothes, like blu-tak.

The working life of the new European millennial is not regimented according to time-and-motion studies; it is teased by the psychological rudder of management. It is nudged, silently, friendly-like.

The future extends to the end of my contract.

LH: The temporal space occupied by Chubz is very interesting, both in terms of the near future political portraits of Farage's rise juxtaposed with his backward looking policies and hand in getting the country "gripped by 1950s fever" (79), and the postscript's allusion to "No Future," (the Sex Pistols' slogan, the title of Lee Edelman's book, and a way of describing the idea of non-reproductivity that I see in your book, both in terms of refusing to rear children, and in terms of resisting a capitalist logic of culture and labor) which sets the book's concerns in a historical context of gay culture and the gay relation to futurity in different moments. Can you comment on this?

HL: I can't help but find the idea of "No Future" dispiriting, disempowering. I suppose it's how I feel right now, how I think a lot of people, especially young people feel, so within Chubz it's a rootless, disaffected, terrified sense of no future. Part of this is the lack of any coherent public political vision of alternative, something fostered by both the government and the Labour Party in order to continue the regime of austerity, of course. But I can't find it in me to buy into an aggressive queer notion of no future as being a stand against biopolitical domination. It's a powerful piece of invective, a weapon against the totalising, aggressive dominance of the family. And I've certainly bought into it in the past, especially when put up against so much "hard-working families" bullshit. But it cedes too much. What queer people (especially young queers) need to survive, I think, and have always needed, in the face of a gender and economic system which has only ever offered an injunction of no future, is the opposite: solidarity and hope. We just need to continue our work in building that. The no future of Chubz is descriptive not prescriptive.

Chubz launched on 28 October at Jupiter Woods, London, with readings from Huw Lemmey, Aimee Heinemann, Timothy Thornton, Jesse Darling, Adam Christensen and Onyeka Igwe.

Published by Montez Press.