Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877).

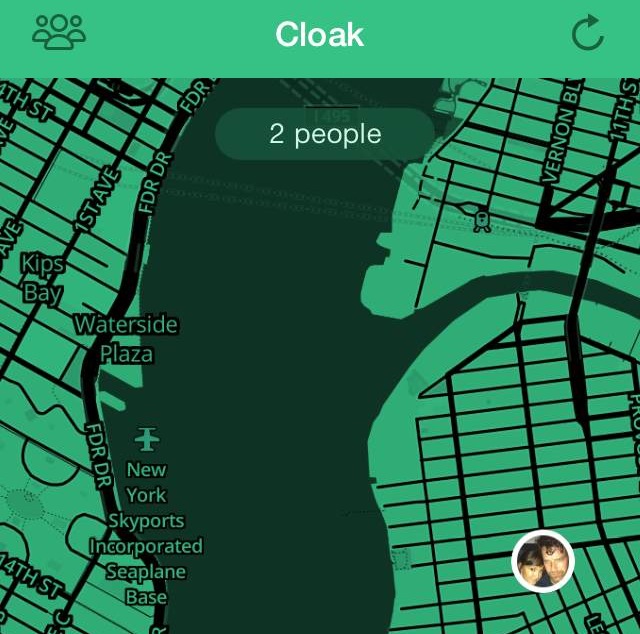

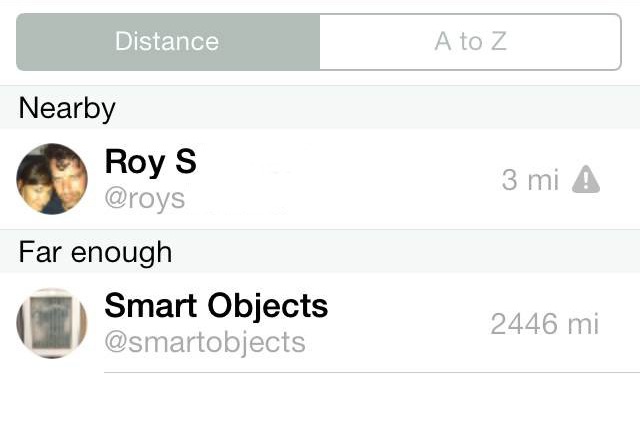

If it's just a matter of avoiding "that guy" or helping its co-creator avoid his ex, then the new "anti-social" app Cloak—which sources your contacts' locations based on their check-ins on Foursquare and Instagram, so that you can avoid them—is just another coddling mechanism that allows us to construct miniature worlds from our "likes," excluding anything that causes us discomfort. This ends, of course, in a boring, predictable, and ultimately doomed utopia, when suddenly everyone is too "Nearby" on Cloak's green-on-black world map, and no one can be "Far enough."

Cropped screen captures from Cloak (iOS app).

The design of Cloak, which shows all contacts' locations by default, makes it easy to do more than just cherry-pick those we don't want to interact with (otherwise known, to Cloak copy-generators, as "particularly hazardous people"). We can also use it to avoid interacting with any of our contacts, or at least the ones who have recently checked in on social media. Co-creator Brian Moore identifies the app's target user as someone suffering from "social fatigue." This could describe any of us, at some point, but it's also a coded way of saying introvert. While Jung's explication of the introvert-extrovert dichotomy wasn't meant to assign value, the "introvert" has long been viewed with suspicion. Recent years, though, have seen the rise of a muted introvert pride movement, with Jonathan Rauch's essay "Caring For Your Introvert" in The Atlantic, Susan Cain's celebratory 2013 book The Quiet, and numerous Tumblrs.

Much of the pro-introvert rhetoric comes down to creativity: There's a widespread stereotype that poets and writers are "naturally" more introverted, and Cain argues that collaboration, often cited as the source of tech-industry innovation, is only possible because of the solitary creativity of people like Steve Wozniak. Arguing about the nature of innovation is a favorite late-capitalist touch sport, and all sort of pseudo-scientific briefs have been authored about the best way to extract creative value from one's employees/oneself. Cloak, however, has nothing to do with creation. You could, presumably, use it to make sure your local cafe is empty of "unwanted friends" (one dark and poetic piece of marketing copy) before going into begin your freelance workday. But then what about all the regulars whose names, much less Instagram accounts, you don't know? Public spaces for composition are thinly protected by any number of unwritten rules, and an app will not save your from their piercing.

Nor does Cloak engage with that other great intersection of the introvert and the internet: social media. It sources from social media, but does not protect the user from social media fatigue; its effects are purely AFK. And actually avoiding people still requires legwork. If Cloak says a contact is walking down the block towards you, you have to reroute; if Cloak says your ex is at your local bar, you have to change your evening's plans. No one gets to disappear (or, vice versa, can be disappeared). Its slogan, "Incognito Mode for Real Life," won't actually be feasible until someone builds a functional blursuit and its legality is ruled upon.

Following McKenzie Wark's call to "reimagine the potential" of emergent tech, we'd like to suggest another use for Cloak: to achieve the social lost-ness so many seek in our cities, not to avoid human contact, but to open ourselves up to the experience of being truly among strangers. This is not freedom from what Baudelaire called "the tyranny of the human face", but rather what he prized as "the singular intoxication" of "the solitary and thoughtful stroller... who loves to lose himself in a crowd" and the "feverish delights that the egoist locked up in himself as in a box...will be eternally deprived of."