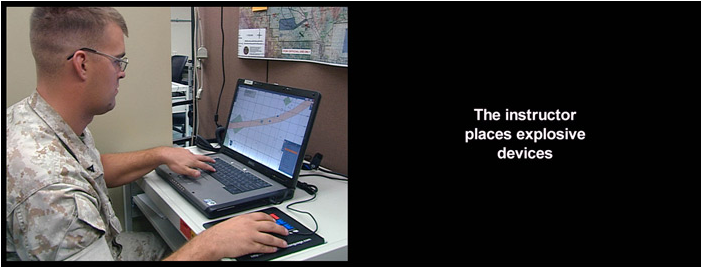

Still from Serious Games I: Watson is Down (2010)

To question the point of view from which a war is narrated or fought, or to say that our image of war is reshaped by imaging technologies, implies that media represents something outside of itself. That it, as McKenzie Wark writes, the media appears to be "merely reflecting 'naturally occurring' moments outside all such apparatus.”

HARUN FAROCKI. SERIOUS GAMES, on view through January 18, 2015 at Hamburger Bahnhof, puts forward an alternative topology of media. Events of violence and war and revolution are not naturally occurring; they are produced, in part, by the apparatus of media. More precisely, these events are produced by workers acting on instruction, who are allowed (by the distancing effects of images, in part) to understand themselves as external observers rather than implicated parties.

The exhibition marks the acquisition of three major works by Berlin's Nationalgalerie: Serious Games (2009 – 2010), Inextinguishable Fire (1969), and Interface (1995). All three of the works are of a documentary nature; the earliest is a short film, while the latter two were devised for gallery settings. The first work encountered in the presentation is Interface, an introduction to Farocki’s process and a reflection on the apparati that affect images and communication. The four videos that comprise Serious Games are spread throughout the majority of the exhibition space so as to lead the viewer deeper into states of immersion with each part. As the viewer exits the gallery, Inextinguishable Fire awaits, giving a historical context for Farocki’s ongoing investigation into militarized industries.

If the three works in HARUN FAROCKI. SERIOUS GAMES can be understood as a kind of schematic narrative of Farocki's work, what comes across is an artist flexible enough to respond directly to changing political and technological conditions, while remaining committed to a political and aesthetic stance throughout. To put this in perspective, Inextinguishable Fire was released the year that Daniel Ellsberg photocopied the Pentagon Papers; Serious Games was completed the year that Wikileaks began to publish Chelsea Manning's leaks. 1969 was the year that internet precursor ARPAnet was launched; 2010 saw the launch of the iPad.

Still from Serious Games IV: A Sun with No Shadow (2010)

In the four video projections that make up the widely exhibited video installation Serious Games, Farocki examines the use of computer game technologies in the training of American soldiers, positioning video games within the context of the military. In part one, Watson is Down, we are introduced to a group of young men in training as they slowly traverse a sandy, computer-generated landscape. Next to the in-game POV footage, we see the soldiers dressed in their camouflage uniforms mundanely sitting at PC desktops in a small room. Part two: Three Dead was filmed during a military exercise in the Mojave Desert in a California city erected solely for this training purpose, populated by some 300 extras playing Afghans and Iraqis. According to Farocki, the city "looked as though we had modeled reality on a computer animation."

Initially, I wasn't aware that the exercise in part two was staged; a similar slippage between reality and simulation occurred in the third part, Immersion. In a therapy session, a soldier retells a traumatic combat experience while wearing a headset streaming a simulated environment which replicates the memory. The soldier seems more and more vulnerable as the session proceeds, revealing feelings of disconnect toward his fellow soldiers and the sight of the mutilated body of his partner. When the session ends, though, the soldier smiles, an audience claps, and we see that this whole scenario was a demonstration of the software used to recreate war environments to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. The final part, A Sun with No Shadow, depicts various elements of the games, such as obstacles click-placed by the trainer: an armed enemy, a civilian, a cat, a Coca-Cola can, the texture of the terrain, and shadows which most make realistic the simulation for training.

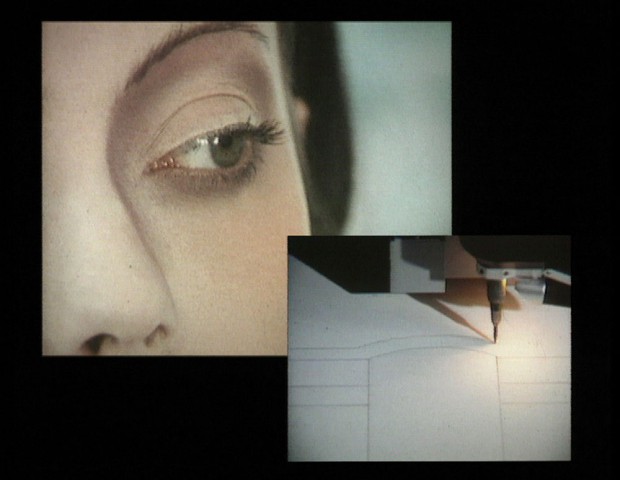

Still from Interface (1995)

In the context of Farocki's larger body of work, Serious Games conveys the idea that media representation or simulation does not merely depict violence; it is implicated in it, accompanying the soldier through every phase of combat from training through treatment. In 1995's Interface, Farocki reflects on his own role within the imagemaking system. The two-screen installation depicts him during the editing process, in which he is always looking at two images at a time, allowing one image to "comment on" the other. Sitting there in front of two screens, Farocki looks much like the uniformed soldiers sitting in front of their PCs engaging with a virtual war, or a scientist sitting in the laboratory observing experiments which will later be introduced into 'real life.' Interface foregrounds labor and its changing technological condition, but also the distancing of the self from larger implications of one's actions through repetitious, procedural behavior and through the construction of a point of view that positions the observer on an outside.

In the more distinctly agitprop Inextinguishable Fire, Farocki critiques the role of consumer industry in the production of chemical weapons during the Vietnam War, in particular, the work of Dow Chemicals. We witness the protocols of scientists involved in the development of napalm. We are engulfed by bureaucratic details, treated so clinically as to be poetically terrifying, but also to create a sense of detachment, a sense of the ambiguity of the point at which our actions or the technologies we work on actually inflict damage. In Inextinguishable Fire we see how the specialized worker can be kept within one sector so closely that they are unable to perceive the larger consequences of their work.

Near the start of the film, Farocki poses a question that seems to get at the heart of many people's anxieties about violence and the media:

How can we show you napalm in action? And how can we show you the injuries caused by napalm? If we show you pictures of napalm burns, you'll close your eyes. First you'll close your eyes to the pictures. Then you'll close your eyes to the memory. Then you'll close your eyes to the facts. Then you'll close your eyes to the context.

It seems, for a moment, to be telling a story of de-sensitization. This narrative, which proposes that screens allow a sense of detachment from "real" events does not ring fully true in an age where our lives on- and off-screen blend so fluidly together. Drone pilots, they say, are turning up with post-traumatic stress syndrome as well. Perhaps the image does not only create detachment, but also certain other forms of attachment.

In the aforementioned passage, Farocki goes on to acknowledge this:

If we show you a person with napalm burns, we will hurt your feelings. If we hurt your feelings, you'll feel as if we tried napalm out on you, at your expense.

Farocki then extinguishes a lit cigarette on his forearm, performing with his own body an instantiation, the hurt, of the image of napalm's burn.

Today, as we bear witness to a new glut of images of violence from around the world, perhaps the lasting import of Farocki's work is not to mistrust media representations of human suffering, but to keep our eyes open to such images, and to remain mindful of our own small stake in creating them—even if it feels like the violence is being tried out on us, at our expense.