MINECRAFT (2011). Installation view, "Indie Essentials: 25 Must-Play Video Games" co-presented by Museum of the Moving Image and IndieCade. Photo: Ben Helmer.

I woke up early on an overcast and windy morning in January and caught the M train up to Astoria to spend the morning playing video games at the Museum of Moving Image. The current exhibition, co-organized by Jason Eppink and Indiecade—an international festival of indie games—is entitled "Indie Essentials," and is home to 25 ready-to-play titles on various platforms. The diverse selection of titles on view were installed with a keen attention to detail, and the exhibition was carefully structured. However, as I walked around the space and played nearly every title on display (or at least every single-player title), a question kept nagging at me: do video games belong in the museum?

This is not to say that I agree with the short-sighted, yet fascinatingly stringent, argument presented by Roger Ebert that video games cannot be art. Rather, "Indie Essentials" posed as an interesting example for the ways in which the museum as a site seems unfit to house this kind of media. This is not the fault of the Moving Image, or the organizers of the exhibition, by any means. The exhibition elegantly exhibited the works, providing ample space for players and viewers. But I'd argue that some of the experience of playing these games gets lost when presented in public space.

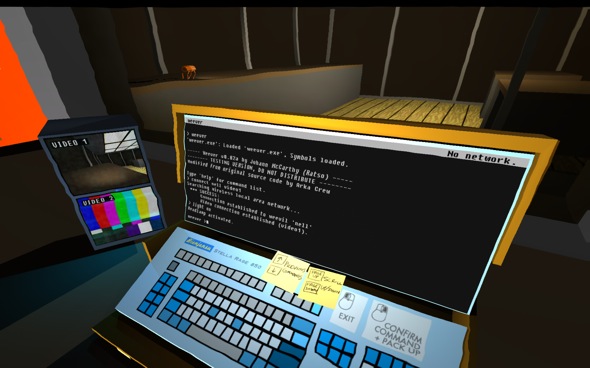

For instance, one of the first titles I chose to play was the Indiecade 2013 Grand Jury Award-winning game Quadrilateral Cowboy. Since this game is currently unreleased to the general public, I was eager to play as much of this as I could during my visit. After spending 30 minutes engrossed in a cyberpunk adventure, I had the sudden feeling that I was preventing other people from playing, and I became self-conscious of my own gameplay.

Still frame from Quadrilateral Cowboy (expected 2014). Courtesy of Blendo Games.

Museums have well-established conventions governing the hanging, mounting, and presentation of art objects, as well public/social interaction (although that's been changing as of late). The video game, however, presents a number of challenges to these conventions, which have become particularly pressing in light of the rate at which video games have quickly become a focus for a number of major institutions.

Pitfalls abound. For instance, the nationally traveling exhibition "The Art of Video Games" installed a variety of old and new video games into large projection booths, making gameplay an uncomfortably public performance, a gesture harkening back to the climatic sequences of Jimmy Woods' playing Super Mario Bros. 3 in The Wizard (1989). In this case, the museum imposed a stale and predigested mode of interaction onto a dynamic and engaging art form.

Another instance of problematic installation occurred in 2011 in the "Talk to Me" exhibition at MoMA with two pieces by Jason Rohrer (an artist also featured in "Indie Essentials"). Rohrer's work—well-known among indie gamers as deeply contemplative and existential—lost nearly all of its affect in the former exhibition as a result of being butted up against eye-catching infographics and pieces of interactive design. Passage (2008)—a tragic five-minute game that takes players through a low-bit sidescrolling meditation on aging and partnership—was installed with little attention paid to its soundtrack. The close proximity of this work to other media objects made it hard to digest, and my observations of players from afar revealed that they were unwilling (or unable) to take the comparatively concise amount of time to fully experience the work.

Installation view of Talk to Me: Design and the Communication between People and Objects at The Museum of Modern Art, 2011. Photo © Scott Rudd.

This is to say nothing about the stunted and unimaginative installation of Dwarf Fortress (2006) in "Talk to Me." This notoriously difficult and time-consuming work by Bay 12 Games was installed in such a way that concentration became impossible. Again, in bringing the game into a museum context, any potential dynamic interactivity of the title has been compacted into a familiar non-functional art object. By stripping the game of one of its fundamental qualities—play—the resulting exhibited work becomes little more than a snapshot artifact.

Titles like Passage and Dwarf Fortress, important works that require concentration and engagement, might benefit from a more considered installation treatment. In "Indie Essentials," works like The Fullbright Company's Gone Home—a rich, 3D interactive fiction requiring meticulous exploration of a suburban home—are given a setting that allows visitors to delve into more attentive gameplay, taking installation cues from video exhibitions.

There is still a problem, however: a good percentage of the games presented in this exhibition do not inherently entice players to dive right in. My initial experience of most games on display during the Moving Image exhibition was either a Main Menu or a stagnant pause screen. In either case, jumping into gameplay ranged from difficult to daunting.

Many of the games on view in "Indie Essentials" are most often experienced in the comfort of one's own home. By moving these titles unaltered into a public space such as the museum, the experience is drastically altered. Of course, museums are not the first place to present public gameplay: this tradition has been well-established by the arcade, and this important precedent should come back into the critical conversation of the ways in which video games can be incorporated into the gallery. Games developed for the arcade had demo screens, enticing prospective players to feed the machine their quarters. Similarly, contemporary art games and indie developers considering the gallery as a potential site for play must take into account the ways in which their titles could benefit from this installation method.

One such game within "Indie Essentials" took the conventions of the arcade game into account, and as a result, it was easily the most successfully installed game in the exhibition. Killer Queen Arcade, a 5v5 upright console featuring combative pollen collection, not only featured an enticing demo title-screen, it also offered a custom adaptation for an arcade-like setting. The title's suitability for public gameplay allowed the museum to host a series of tournament nights to be held over the course of the exhibition, offering a further avenue for public engagement.

Killer Queen Arcade (2012). Installation view, "Indie Essentials: 25 Must-Play Video Games." co-presented by Museum of the Moving Image and IndieCade. Credit: Photo: Ben Helmer.

The question becomes, how can a museum or gallery apply this strategy to games like The Chinese Room's Dear Esther (2007/2012) or Tale of Tales' The Path (2009)? It seems that developers themselves need to be convinced that the museum is an important site for the display of their work, worth the effort of creating a version suitable for public presentation. The idea that a work should be altered for display in the museum may rouse the ire of purists, and it raises unanswerable questions about archival titles. But until this begins to happens, museum exhibitions of video games can only ever be partially successful.

"Indie Essentials: 25 Must-Play Video Games," co-presented by Museum of the Moving Image and IndieCade, is on view at the Museum through March 2, 2014.

You're entirely correct when you write that "some of the experience of playing these games gets lost when presented in a public space". It's a concern that we regularly grapple with when we show cultural artifacts out of their intended context.

In the beginning, as you hinted, showing video games was much easier: arcades were not dissimilar to gallery contexts, and the games adapted to galleries well. Now games are much closer to us, made for devices that are also used to write emails and edit photos and often requiring long-term engagement, access to social media accounts, or regular interactions with thousands of other players. Showing those games to public audiences is, as you would expect, super challenging.

But the question "do video games belong in the museum" privileges the museum over the artifact. A more nuanced question is: what is the best way to present an artifact to an audience? (It may or may not be a museum. It may be a conference, a demonstration, or a tournament) The answer depends on what one's goals are in presenting the artifact.

If the goal is to provide a deep experience akin to owning a game, then the best experience is owning the game. Unlike a work of fine art or rare historical artifact, this is something that is frequently possible because games are typically commercial products. Barring that possibility, the next best context is probably a library: games libraries are at the heart of every academic game program for a good reason.

But there are other valid curatorial goals, including context, community, and discovery. Taking Indie Essentials as an example, the vast majority of our visitors do not know what an independent game is. Just creating a space where visitors can encounter these games and be exposed to the story of the independent game is a success by those measures.

Unfortunately, there's no one way to present every kind of video game in a way that meets every goal. Now that more museums are grappling with video games, they are bringing their own perspectives and approaches to solve these problems, and all of us will benefit from that.

Also (at the risk of having a monologue with myself here) I should note that 7 developers created gallery versions for the exhibition at my request, and another 2 already had gallery versions at the ready. Others declined to do so citing time/resource constraints (never philosophical concerns).

This is a very interesting post as I am currently asking myself this type of questions as I am curating games and indie games shows. I just curated an exhibition of games and artistic installations related to games, untitled Games Reflexions.

We visited this show with art students and the first reaction was that the temporality of games is quite difficult regarding the avarage time of an exhibition visit. We immediately thought about time based arts and how we could make exhibition versions of games (allowing also an automatic restart) but I do agree with you, it would mean that developpers consider the exhibition as an aim, which is not the case and I perfectly understand.

Museums are not the objective, the objective is to touch different kinf of audiences and make discover a wide variety of games to a larger audience. I also think that mixing disciplines and audiences often offers a richest perspective.

The other critic I got from Games Reflexions is that the playful experience doesn't allow enough distance to consider the concepts presented and the tehory behind the games… Still learning!

http://www.isabellearvers.com/2014/02/games-reflexions-contemporary-art-space-le-carreau-cergy

Hi Jason, Thank you for the thoughtful responses! And thanks for making your comment here on the site. A lot of people chose to respond on twitter.com, a for-profit website that sells user data to advertisers.

I'm interested in this statement: "Just creating a space where visitors can encounter these games and be exposed to the story of the independent game is a success by those measures."

There is, for sure, some level of tension between the needs of general audiences and sophisticated visitors. But–and now I'm speaking more generally, not about your exhibition–I'm curious if this is the standard most larger-scale video game exhibitions are held to. Which video game exhibitions have worked especially well for more sophisticated gamers, like Nicholas?

And have any worked especially well for both the novices and the sophisticates? Like a Kubrick show, for video games.

And (also monologuing) the other question: is "firsthand gameplay of otherwise difficult to experience titles" the central attraction that an exhibition might hold for most serious gamers, or is Nicholas unique in this regard, as in so many others?

I can imagine that it is an important attraction. It seemed like he really wanted to play Quadrilateral Cowboy.

I don't think the tension is between "general audiences and sophisticated visitors" as much as it is about grappling with cultural artifacts that have vastly different intentions, contexts, and needs. We're using the term "video game" to describe everything from QWOP to Eve Online like tetherball and football are both "sports".

QWOP is relatively easy, but how the hell do you exhibit Eve Online? No one has cracked it. MoMA took a commendable stab at it, but they ended up just exhibiting an infographic snapshot. You didn't begin to glimpse the mechanics, strategy, social dynamics, or moment-to-moment decision-making, much less have a chance to play it. Put behind the wheel, you would have no idea what to do, or even why you were doing it.

Does that mean Eve Online shouldn't be mentioned in museums? Of course not. It's a significant game.

Foregrounding the"firsthand gameplay of otherwise difficult to experience titles" as a central attraction privileges a fine art perspective of the purpose of a museum and an exhibition, one that relies on scarcity. But I'm not sure most video game exhibitions are, or can be, for "serious gamers" anyway, unless they are exhibitions of games specifically created for exhibition-like settings. Luckily for Nick, Quadrilateral Cowboy will be out in a couple months and he can play it for as long as he wants from the comfort of his own home, which is surely more desirable than the wooden stool we provide.

Jason:

I want to second Michael's thanks for posting directly to the article as opposed to third-party commercial social networking sites.

I also want to preface that I appreciate you comment very much, especially with regards to thinking of games as having the same problem that other cultural artifacts face within the museum. This gesture is a testament to the consideration you put forth within the exhibition.

My question about the games belonging in the museum is meant not to leverage the museum, but actually the artifact. Maybe these titles are "too good" for the museum - or too dynamic as an artifact for museums at the moment. I think that the games deserve better treatment - not that they are "abused" in this setting by any means, but that the depth of their importance extends beyond the ways in which they get truncated into a museum space. How does the museum change to reflect the ways in which culture is becoming more dynamic? How can a gallery become more like an arcade? Jon Rafman's event of a Street Fighter tournament during his exhibition at Zach Feuer is an attempt at doing so.

I appreciate that you worked with developers to make gallery/museum versions of their work for the exhibition, but I wonder how this collaboration could include not just the game itself, but the environment in which it is presented. How can the wooden stool you provided become a periphery of the game? Or the device that you use to control/manipulate the game? Shane Mecklenburger has done this a bit with this "Fortress of Solitude" work, though he doesn't really call that work a video game (not to speak for him, but I'm pretty sure he thinks of them as sculptural objects).

I often think that being able to provide takeaways for an exhibition expands the experience of that work by making it accessible outside of the gallery. Could future exhibitions of games include download codes for personal consumption to be included with the price of admission? Could that be a way of using the museum as a hub to distribute these artifacts? ie using the museum as a physical/non-online Steam Sale or Humble Bundle?

These are questions that continue with me since seeing the exhibition. (hopefully) Good questions coming from a (definitely) good show.

related thoughts: http://www.columbiaspectator.com/sites/default/files/EyeOnlineSept29.pdf