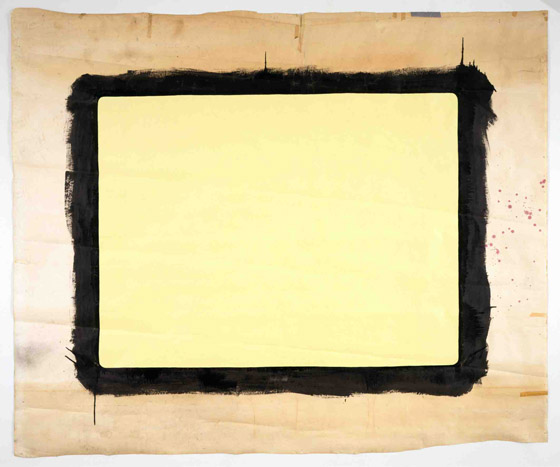

Tony Conrad, Yellow Movie 12/17/72

If, as Tony Conrad might have us suppose, a Movie is light and any marking of the passage of time, what is Documentary Cinema as a category? In fact, the Minimalist structural filmmaking practices of Conrad and others share concerns with documentary's base impulse, namely the transmission of a "factual record or report."

As screen culture settles into its well-earned ubiquity, we must revisit old questions about the where and the what of cinema as an object and what constitutes something separately known as the "cinematic." All cinema is, on some level, depictive, not necessarily by choice, but rather by inevitability. As fictional as any narrative may assert itself to be, it is also a real event. Every book is a record of someone and something somewhere writing and printing it in real time, and so too every image on screen. Regardless of visual effects and editing, the moving image is, at its root, depictive, depicting its own movement as a bare minimum.

With this in mind, is a digital clock cinema? Is any screen producing light at any time—picaresque and episodic as devices are woken up, sleep, wake up, sleep, screens within screens are opened and closed, sleep—also cinema? It appears to me that a movie or television show begins when the screen is turned on and ends when it is turned off, regardless of any durational claims made by an individual work.

Still from Dara Birnbaum, Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry (1979)

A month or so back, I had the pleasure of seeing an abridged retrospective of Dara Birnbaum's shorter video works. Birnbaum was present and spoke with the audience after the screening.

What struck me most were some comments she made regarding the screen-area as a depictive space, a space with the potential to capture or document some event, affect, or qualia, in time, and to attempt a broad accountability for its subject's complexity. Birnbaum described the early days of video and the advent of screen-in-screen editing technology as marking a historical shift with regard to the way information is presented and indexed on screen. No longer were occurrences on screen "calling" to objects or occurrences off screen; now, they could call to other objects sharing the same depictive field by way of a simultaneous pseudo-cubist realism.

Birnbaum also discussed a video she made with the composer Glenn Branca in which Branca and a group of musicians perform at New York's legendary Mudd Club in the late 70s or early 80s. Using a dark, abstract screen-in-screen effect, and overdubbing audio of the thunderstorm outside the club on the night of the performance, the video folds in sensory, affective, and allegorical information simultaneously, entangling the virtual and the actual in an expanded-field depiction. She noted that Branca was unhappy with the video because it wasn't simply a reproduction of the performance.

The potential imbued in screen-within-a-screen has enabled an aesthetic family of home shopping networks, game shows, news networks, pop-up video, pop-up ads, and the graphic user interface of our contemporary internet. All share an approach to aestheticized data: shifting infographics that visually index the economies orbiting around and intersecting with the object of our viewing. Which is to say, these windows didn't open themselves (for the most part).

Screen capture of YouTube's recommended videos for Sam Davis.

I experience this phenomenon most acutely via YouTube. Last year, I made a movie called Slowly We Rot, assembled entirely of YouTube clips I ripped using a website called clipconverter.cc. Most of what I watched while researching and editing this project (and most of what I watch on YouTube, regardless) is live concert footage of the sort I imagine being traded on videocassettes 20 years ago.

As a result of regular use, there is a column at the right of my screen recommending videos which YouTube has, in procedural collaboration with me, deemed content Related to my current viewing concerns, and therefore Related to the concerns of the object of my viewing, becoming subject at the center of a broader historical network of culture and capital. Unlike televised iterations of screen-in-screen graphical user interfaces (or GUIs), things like ads for other television shows or stock tickers, I can actually click through to any YouTube recommendation, my own desire intersecting with history, organizing culture for myself and others.

History is performed, in the case of YouTube and its user, as a creative act of delineation, incorporating countless economies of affect, data, qualia, etc., our taxes, our photos, a clock, a calendar, a calculator. YouTube's mode of on-screen depiction and incorporation of its surrounding context has its less interactive roots in television, but a peer in the structural Representational cinema of artists like Conrad and Birnbaum. By depicting the behavior of the viewer through targeted recommendations and histories even during the act of viewing, traditional cinematic time becomes depictive time, slow time. This is not merely process cinema, however, nor self-reflexive redundancy marking its own passing. YouTube viewing has the potential to include the Bergsonian "any moment whatever," Whatever's Around In The Expanded Field.

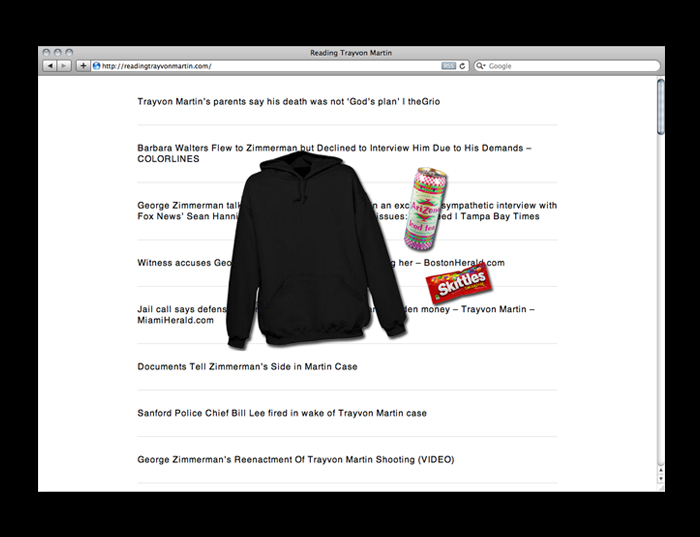

Martine Syms, Reading Trayvon Martin (2013)

Martine Syms's readingtrayvonmartin.com is a public website collecting links to news and opinion articles orbiting the event depicted, the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman. The overlaid images of a hoodie, iced tea can, and skittles bag are nearly platonic in their ubiquity; flattened product shots of the type used by Amazon and tiny procedurally-generated Google ads. My own computer's clock and my internet connection become formal edges for the work, a structurally cinematic delineation à la the black frames around Tony Conrad's Yellow Movies, an instance of what John Keats might call negative capability. The website as situated both within time and the internet indicates the end of point of delineation and autonomy, an inevitably and irreparably open end where the Content meets the rest of the universe.

Detail of Carson Fisk-Vittori, Women Weed & Weather, at Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago.

Off-screen, Carson Fisk-Vittori, an artist living in Oakland, CA, makes clean formal arrangements using consumer gardening products, water bottles, cell phones, and lots of live plants. The plants co-exist with commercial iconography flatly representing The Natural, casually assertive biomorphic branding clip art arranged in colorful harmony as "freestyle ikebana," a variation on Japanese ikebana flower arrangement that Fisk-Vittori describes as celebrating "creative design and innovative materials not limited to plants."

Free Style arrangements attempt to reflect their surroundings, and through their inclusion of modern materials compile an updated image of the world we currently live in—some acknowledging dust bunnies, plastic parts, discarded Dr. Pepper cans, candy wrappers and other technological wonders culled from our contemporary landscape.1

I like to imagine that the plants in Fisk-Vittori's work constitute a cinema of their own. A slow moving image in real time, at the center of orbiting Related nodes performing the intersecting economies on display.

In the work of both Syms and Fisk-Vittori, documentary cinema is material and even sculptural, a cinema of clocks, links, and photosynthesis that manages to temporarily depict simultaneous economies in real time, rejecting structures enforcing the subjugated informe and depicting the incidental and everyday as an essentially iterative, procedurally and thus politically generated component of the documentary body.

These intersecting economies suggest a cinema that is radically participatory, turning us, if we so desire, into aesthetic prosumers. This ikebana take on practices of depictive capture implies an accessible and potentially subversive set of generative circumstances, which is to say, a sandbox.

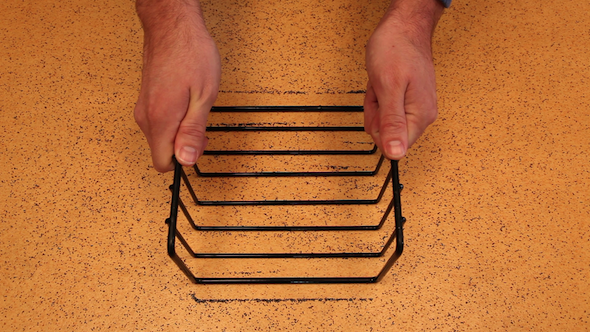

Still from Paul Salveson, Instructional #3 (2014)

Paul Salveson, an artist whose work has its roots in depictive photography, reveals the latent alien qualities in the arrangement of everyday life and, occasionally, makes minor adjustments. Not only does Salveson depict the strangeness of the sandbox itself, but he's acting upon it, akin to Fisk-Vittori's freestyle ikebana, but like a YouTube instructional video insisting that we can all just do it if we want to. In a recent video called Instructional #3 (which he was gracious enough to upload to Vimeo for this text), Salveson imitates the well-lit depictive space of YouTube How-To videos, performing a series of actions within that space and narrating his actions in real time. Despite the strange abstract quality of the imagery, there is no suspension of disbelief required while Salveson unpacks the scene depicted, exploring its nuances in a way that, wonderfully, doesn't make it any less strange or alien. What constitutes the edges of a work like this? Given the tools to recreate the actions in front of us, are we, the viewer, the cinematic delineation of this documentary, the edges marking its frame?

The cinemas of Tony Conrad and Dara Birnbaum are cinemas of the divining rod, instances where cinematic capture is the same thing as any event's material expression. While Salveson's work has more in common with traditional cinematic viewing experiences, it performs the same documentary function as the work of Syms and Fisk-Vittori, a carefully freestyle depiction in real time, a documentary of the swirling vortex, actions performed on images and images performing actions, the ability to depict the experience of living under late-capitalism, or universe circa 2014, or whatever you want to call it. This could be New Documentary.

1 From an unpublished text by Fisk-Vittori and collaborator Jasmine Lee. Due to an editing error the block-quoted paragraph was not attributed as a quote in an earlier version of this article. The post has been updated.