Filmmaker Hito Steyerl has described the aesthetically-coded power dynamics at play between the "poor" and the "rich" image that infiltrate all aspects of contemporary video production. Beyond the dialecticism of her argument, which encourages deeper engagement with "degraded" pictures and a sort of abstract suffering through circulation (at least in terms of pixels), there remains a wide spectrum of mediocre to fair digital images for artists and filmmakers to deal with, and a host of issues concerning the resolution of visual matter, both new and appropriated. Just as collage and photomontage were once essential techniques for tinkering Dadaists, today the manipulation of picture quality has become a distinct strategy. I spoke to Berlin-based artist James Richards (UK) about his particular practice of presenting still and moving images of all registers in the space of the gallery exhibition, and the point at which an image breaks down into a feeling.

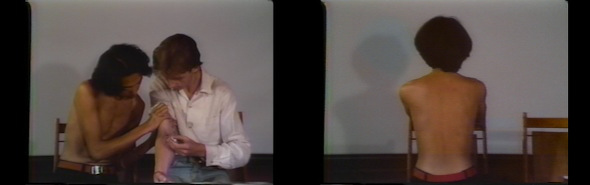

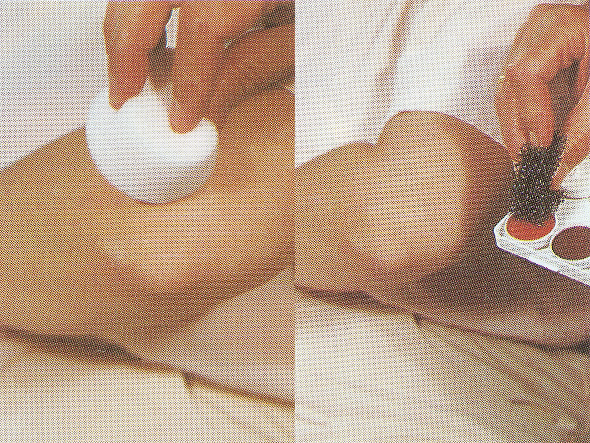

erKR: In 2012 you programmed a screening for the Serpentine Gallery Memory Marathon. Surface Tension had some incredible films in it, including Paul Wong's Bruise (1976), which records the skin-level effects, in real-time, of transferring 60 units of blood between friends. That program really seemed to develop a metaphor between skin and screen—a form of intimacy that visually explodes the technological concept of a "touch screen"—something that I think also comes through in the composition of your own work, including Rosebud (2013), which premiered at Artists Space in New York in January.

Stills from Kenneth Fletcher/Paul Wong, 60 Unit; Bruise (1976, Digitally Re-Mastered 2008). 5.25 min., stereo, colour, English, single-channel.

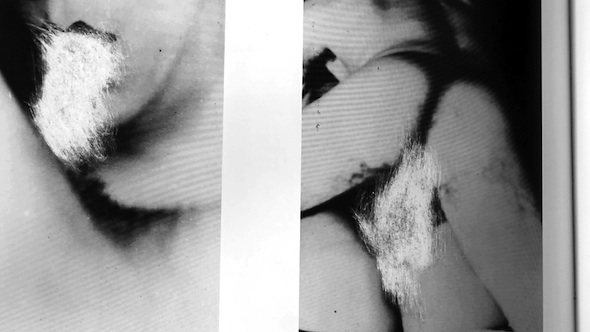

JR: The censored images in Rosebud were shot in a library in Tokyo. I came across them by accident while researching there in the spring of 2012. The books—monographs on Mapplethorpe, Tillmans, Man Ray—were being imported into Japan from Europe when they were stopped by customs officials. Local law in Japan forbids a library from having books with any images that might induce arousal in a viewer, so after negotiations with the director, it was agreed that customs workers would go through the shipment and sandpaper away the genitals from any contested images. As you say, the video somehow is focused on the violence of the action of sandpapering—the point where glossy black printer ink gives way to the scuffed and bruised paper stock underneath. There's something intense but also futile in these marks. The video is a study of rubbing against and along different surfaces: the meniscus of water over the print, the elderflower rubbed along a boy's body.

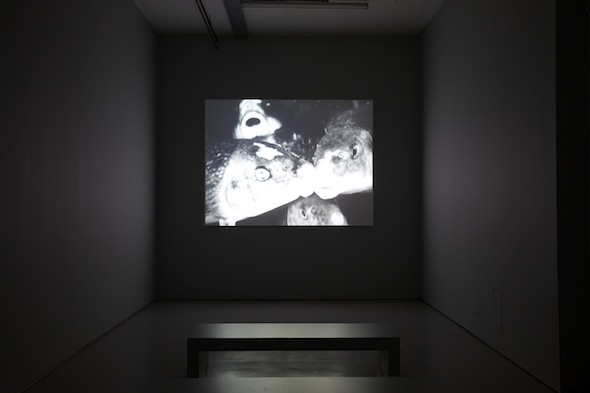

James Richards, Rosebud, 2013. HD Video, 12 minutes 57 seconds. Courtesy the artist; Cabinet, London; and Rodeo, Istanbul. installation view, "Frozen Lakes," Artists Space, New York.

KR: To me, Rosebud is explicitly charged and has both a quiet violence (the censored photographs) and a very playful sensuality (the soft-core passages) that makes it the most erotic of your recent work. It seems to mark a visceral shift that is perhaps less reliant on the aesthetic and atmospheric "aura" of the earlier collage works.

JR: Well it's less reliant on the auratic properties of low-resolution online video, or VHS, though of course the exploitation of the vertigo one experiences when looking at moving images of such super crispness and high definition is itself a fetish, and one I was interested in exploring. Rosebud really pushes and pulls around a restricted set of image sensations: the long claustrophobic takes of the sandpapered book pages, the erratic searching shots of puddles and streams shot with an underwater camera, and then the sensual, lightly erotic or arty images. My previous work kind of drifts around more, returning less to the same place, whereas this piece feels like a study.

Stills from James Richards, Rosebud, 2013. HD Video, 12 minutes 57 seconds. Courtesy the artist; Cabinet, London; and Rodeo, Istanbul.

KR: Your previous work, from 2009 and earlier (Active/Negative Programme, 2008; The Misty Suite, 2009), often collaged together film clips from archives like the LUX collection along with video ripped from discarded VHS tapes. I'm curious about the way you choose and process media; or, as you've described it "work out your feelings about material." Can you speak a little bit about these feelings, and your response to "the image," as a viewer?

JR: My working process has always begun with the idea of collage; of bringing disparate things together in such a way as to make something new, but also to keep hold of the sense of those fragments being very different—or from very different sources—each with a life of its own.

Three stills from James Richards, The Misty Suite (2009). Video, colour, sound, 6:47 min. Courtesy of James Richards, Rodeo Gallery, Istanbul.

Really early influences were mostly musical, or sonic; albums like Lifeforms by The Future Sound of London, Chill Out by The KLF, On Land by Brian Eno, the exquisite, ecstatic early tape work of Steve Reich and the revelatory creation of place that's suggested in the electroacoustic compositions of Luc Ferarri.

I was drawn to the idea of gathering and "de-familiarizing" material. I saved up and bought a sampler and started mixing long passages: late night radio, whole songs passed through filters, sessions of my own improvisations on piano or with some crude lo-fi electronics like Dictaphones and guitar pedals. So it started in sound—when I worked on a number of video projects that incorporated work from the LUX archive along with found and self-shot footage, I was interested in a sort of absent—or raw—authorship; the holding up of information. In more recent years the videos have shifted; they are more focused, and I feel they are more about a way of looking than about re-presenting or appropriating.

KR: That's an interesting way of putting it—"a way of looking rather than representing." Do you think the endless production of visual material (not necessarily in art, but in all modes of branding, advertising and cultural dissemination these days) makes "looking" a more artistic task? And how does curating relate to this, if at all?

JR: In terms of curating, I've been interested in submerging work by friends and other artists into pools or compilations of more anonymous or readymade material from online or secondhand video sources, but this year I found myself really wanting to make the kind of group shows that I would like to see, rather than testing authorship. "If Not Always Permanently, Memorably" (Spike Island, 6 July–1 September 2013) included seven works; films by Su Friedrich and Cerith Wyn Evans, videos by Stephen Sutciffe, Steve Reinke, Stuart Marshall, and Paul Wong, and a slide work by Christodoulos Panayiotou.

"If Not Always Permanently, Memorably" (2013). Installation view. Photograph by Stuart Whipps.

For me, curating is the luxury to engage an artwork in a deeper and more extended way than usual. It's a way of learning about how the artworks work on me. The works in "If Not Always Permanently, Memorably" all share a kind of delicacy, and a sense of the cryptic in the use of language and poetry. Something beautiful that also has a sense of trauma, or a sense of something memorialized. It was a real pleasure to bring them all together. This project coalesced over about a year—very much in parallel with Rosebud. Thinking about all these works that I admire gave me a certain confidence when it came to making Rosebud. There's a sparseness I wanted to bring into that piece; a focus via the intense gaze of the camera and a much tighter palette of footage.

Su Friedrich, But No One (1982). Installation view at "If Not Always Permanently, Memorably" (2013). Photograph by Stuart Whipps.

KR: A lot of young artists now produce video and other work strictly for online distribution, for more or less "personal viewing," even if mediated by social networking sites, YouTube or Vine. But a lot of the found footage in your previous work actually comes from UK public television—after-school specials or other instructional programs that teach drawing or elocution. Do you feel any sense of nostalgia for the public consumption of imagery, specifically video?

JR: Not really. There was a period in about 2008 or 2009 where I was gathering a lot of VHS tapes from charity shops in London; you could buy about 10 for a pound. So I would scoop them up and sit in my studio to watch through them, going kind of numb, watching on fast forward—waiting for moments or odd glimpses of things that would snap out at me. The sort of things that work outside of narrative or logical forms of communication, and instead hold a kind of atmospheric, hypnotic or affective resonance. Over the years, I've had phases of looking in different places for content. I'll mine a source for a while and then get interested in something else. At different times I'll look to a different technology or equipment. You always want to keep on your toes and not get too settled.

KR: We've talked before about how your editing method is more rhythmic or emotional, which stems from your work with sound—building suspense through transitions, repetition, layering—a practice that involves particular choices, such that the end result is neither overly determined nor entirely random.

JR: I think a lot of the work in editing or composing a piece is in feeling out the internal rhythms of the footage that I'm using, and letting that guide the sound of a particular section and how I work it into the next. One of the things I try to do in my work is rein in or curb randomness to just the right degree; to produce something that is perfectly illogical or somehow off. So it's a matter of finding the right balance to this, the right disruption. A few years back I was introduced to a wonderful and succinct term at a talk by Cerith Wyn Evans and John Stezaker. Cerith said that John, who taught him at Central Saint Martins in the late 1970s, described "spot off-ness" rather than the spot-on. This term captures the perfectly jarring cut or shift that makes an artwork linger in the mind of the viewer.

KR: Would you say there is a vernacular visual imagery that is particularly dominant today, now that mobile devices have fractured the experience of mass television broadcast? Has this prompted you to use more of your own footage?

JR: I'm not sure about this. I think the desire to work with my own footage comes out of a desire to make the work more direct. I don't know what this directness really is—I don't know how to make an artwork really honest and open—but I have had a sense that I would like to bring more of my lived experience into the work. And maybe this is where the TV thing comes into it; I think my early videos really spoke of a kind of late-night hazy trawling. Drifting through this kind of marginal or "off-peak" material. Now I think that atmosphere or tone is still present, but I feel I've also been bringing in more of myself: the natural world, friends, and diaristic material. By continually carrying around a camera and sound recorder, I can tape little visual or sonic moments as I encounter them. Then, rather than searching for footage as I used to, I can dip into this growing mass of material and extract things for use. The sensibility is still that of a gleaner rather than a filmmaker, but now I'm appropriating more from myself.

Though my work deals a lot with the disjointed, the fragmented and the random, I feel I'm very much trying to make something expressive. Something where I'm present, or at least the viewer senses a singular personal subjectivity at the heart of it somehow.

KR: Staging is an important part of your video installations, and you've even helped design some video exhibitions ("A Detour Around Infermental," Focal Point Gallery, 2011). Isla Leaver-Yap has commented that there's a certain set of actions a viewing body must perform in order to "enter into" one of your works. Yet seating wasn't provided for the installation of Rosebud (2013) at either Artists Space ("Frozen Lakes," 2013) or in the version currently on view at the Arsenale for the Venice Biennale. How do you approach the manifestation of your work?

Installation views of "Infermental" curated by George Clark, Dan Kidner and James Richards. Focal Point Gallery, Southend On Sea.

JR: I really like working in physical space. Probably I would be a sculptor if I could. I'm always finding reasons and ways to work with the space of exhibitions; but always tentatively, always going back to the comfortable production space of the computer where I can work constantly—doing and undoing, adding or removing material, saving multiple versions for later sifting and editing.

For me, the staging of a video has often been a device to hold the viewer and the really disparate video source materials together. In Not Blacking Out, Just Turning The Lights Off (2011), the mint carpet and sinister lobby walls are a way to narrativize the otherwise fragmented material.

James Richards, Not Blacking Out, Just Turning The Lights Off (2011). Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate.

Rosebud is different in the sense that it works from a much tighter selection of images unified by black-and-white post-production and a very stark, rasping and airless soundtrack. It didn't really need any other devices. I've shown it now twice on a large flatscreen (80") and this seems to emphasize one of the main formal themes—the play of light and friction on a skin or liquid surface.

KR: In a recent e-flux journal article, Jon Russell wrote: "Real rhythm . . . according to Deleuze and Guattari [is] what 'renders duration sonic.' Duration is the détournement of linear, logical time, the rendering pre-posterous of time . . . the nonsense of lived time." It's a seductive description, particularly in regard to the implied potential for restructuring - or undoing - both (industrial) cinematic time and the seeming perpetuity of online time (only limited by battery-driven devices). It makes me curious about the sonic aspect, and your pairing of aural and visual rhythms.

JR: In Not Blacking Out…there are really distinct periods of suspense where I'm trying to stretch time. For example, there's a stuck loop of a cigarette dropping to the floor. It's a heady, atmospheric moment that cuts back on itself over and over, and as your mind wanders you find yourself focusing on different part of the passage: image, sound, lighting, or the instance of the cut. These tight loops can really create a situation where a fragment feels like it is being turned over in the light and inspected from different angles.

Two stills from James Richards, Not Blacking Out, Just Turning The Lights Off (2011). Digital video with sound.

For me, duration is about playing with the experience of time for the viewer. Silence (both sound and image) is important for this. The light bulb at the beginning of Not Blacking Out…. makes you wonder if there's anything happening, or if anything is going to happen. It's really just a kind of dumb one-liner: an unplugged bulb rocking back and forth and illuminating itself. But as time goes on it becomes sinister; you're suddenly more aware of the person sitting on the bench next to you. Drama can be conjured through duration.

KR: What will you be working on next?

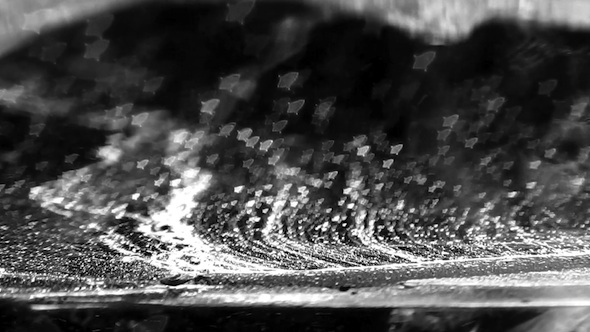

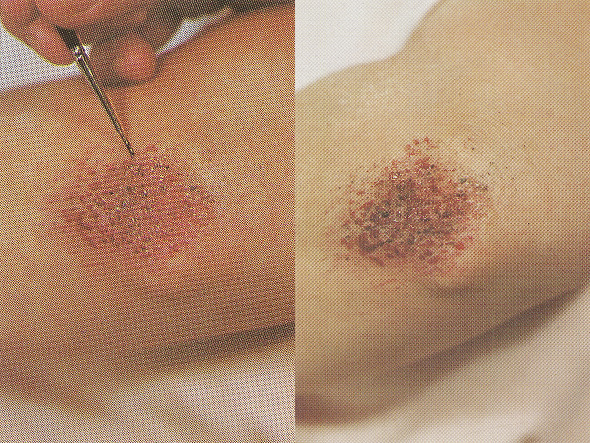

JR: Continuing my interest in working with still images by means of time-based formats, I recently finished The Screens (2013), a row of four slide projectors that present a sequence of 35mm slides, all found images, scanned from a Dutch book on how to apply theatrical make up. Shot against these really beautiful soft backdrops, they oscillate between the hammy, the kitschy and the violent in a focused sequence on fake wounds and bruises. The half-tone of the image mingles together with the photographic surface of flesh; they're mannered, mysterious and elegant. Several show a hand entering the frame, which lends a strange sense of tenderness to the images. Slide projection is a limited and highly specific analog format, but it felt exciting and also possible to work with such retro, even reactionary equipment in this context. There's a certain theatricality in the sound of the shutter and the appearance and mechanics of the projector. So it's all about finding the right format for the images that I work with; I wanted to present The Screens in a way that is deadpan but also playful and rhythmic.

Images used in The Screens (2013). 35mm slide installation.

I'm starting to build up a new bank of footage from classic and underground cinema. And I'm working with a cameraman to shoot a bunch of 16mm in the studio, which I'll transfer to digital to work with. I'm hoping to amass an archive that slips between self-generated and appropriated material that somehow feels cinematic: close-ups, tracking shots, details. A curtain blowing in the wind, a cup of coffee being put back onto its saucer; stylized and studio-produced, controlled looking. I don't know yet what I'll do with this material, but I'm interested in the ambiguity between the sampled moments and my expanded own passages.

I'm also finding new ways to work with sound. This winter I will be spending two months at the Electroacoustic music studio of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, to develop a multi-channel sound work that will be shown in Beijing in 2014. Sound was my entry point into digital media and has always been at the core of my work with video, so it feels great to be returning to it in earnest—in a way that is structutal to the exhibition, rather than merely infecting the visual. The show will be very simple—some architectural modifications to the room, some speakers and amplification hardware, some light. A lot of the sonic material I'm experimenting with for this originates in my voice. Utterances, bits of songs or humming to myself—I'm trying to take the close mic's intimate lo-fi sound and really sculpt it out into something architectural.

James Richards's solo exhibition, "The Screens" is currently on view at RODEO, Istanbul (7 September – 27 October). His work is also featured in "The Encyclopedic Palace," 55th Venice Biennale (1 June – 24 November); "Meanwhile… Suddenly, and Then," 12th Lyon Biennial (12 September – 29 December); and "Speculations On Anonymous Materials," Fridericianum, Kassel (29 Septemeber 2013 – 26 January 2014).