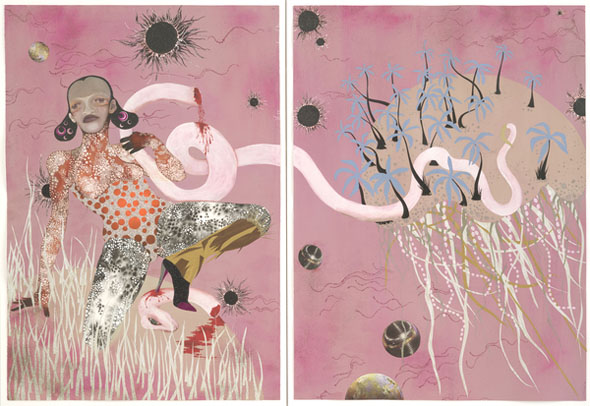

Wangechi Mutu, A'gave you (2008). Mixed media collage on mylar, 93" x 54".

The violent and ambiguous encounter depicted in A'gave you (2008) encapsulates the force and intent of Wangechi Mutu's collages, the highlight of her ongoing retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. A blue, thick-rooted, and out-sized version of the New World monocot bends to a violated female pseudo-cyborg. Her eyes, cheap black speckled pearls, are replicated in the plant's ovary. The kneeling figure's torso, head, and left arm are thrown back in disinterested submission; her right arm is lost to perspective and/or trauma. Gold sparkle and blood explodes from her chest as she births, or pisses, a long, fat strand of bright yellow-orange which forms a new root-system beneath both her and the plant.

Mutu's strangely lucid mixed-media mylar pieces contort the sexualization of black women in consumer society into glittering, gorgeous grotesques. The twin pieces 100 Lavish Months of Bushwhack (2004) and Misguided Little Unforgivable Hierarchies (2005) feature female figures hobbled with hippo hands, faces stitched together from pornographic images, golden skin, and exploding motorcycle high-heels. They also depict differing levels of power among multiple exploited figures. The End of Eating Everything (2013), Mutu's first foray into animation, features the head of Santigold gnashing a gyring flock of black birds with bloody chompers. Slowly, the plane Santigold exists on expands to reveal that her face leads a massive she-planetoid, comprising writhing limbs and embedded, useless machinery, powered by her/its own gaseous effluent. The piece is truly disconcerting and accentuates Mutu's often overlooked theme of ecological disaster.

Wangechi Mutu, The End of Eating Everything (2013).

Mutu's sketchbooks, some of which stretch back as far as her undergrad years at Cooper Union, are also on view; one of the displayed pages reads: "in Your mind you envision Yourself a butterfly But you still find yourself on your knees." Her figures, assembled commodifications only human enough to be complicit in their own subjugation, could be seen as an expansion of this phrase: spiky hope born of spangly misery. Sometimes this is made too obvious. Yo Mama (2003) is a kind of non-portrait of Nigerian politician and human-rights activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti vanquishing a serpent. This Mutuization of the political/social mural has little of the impact of her less triumphal pieces.

Wangechi Mutu, Yo Mama (2003) Ink, mica flakes, pressure-sensitive synthetic polymer sheeting, cut-and-pasted printed paper, painted paper, and synthetic polymer paint on paper. 59 1/8 x 85 inches

In a 2010 interview with Daily Serving, Mutu stated she attempts to use "the aesthetic of rejection, or poverty, or wretchedness as a tool to talk about things that are transcendent or hopeful..." The encounter depicted in A'gave you is both transcendent and non-consensual, and the plant's intentions are inhuman, unknown. The warrened figure can still bring forth the new, strange, and beautiful, but only through further violence against the self.

The curatorial text accompanying A'gave you connects Mutu's work to Afrofuturism, "an aesthetic that uses the imaginative strategies of science fiction to envision alternate realities for Africa and people of African descent." When looking at a work like Mutu's A'gave you with this concept in mind, the implication is that the strange and violent birthing process she depicts suggests a new type of life, a radically different and therefore potentially liberated future. But in addition to opening up such readings, thinking about Mutu in relation to Afrofuturism also helps to situate the work in relation to other practitioners.

The term "Afrofuturism" was coined by Mark Dery in his 1992 essay "Black to the Future," which asked why so few African-Americans have created SF when they are "in a very real sense, the descendants of alien abductees," whose bodies are all too often impacted by the tech of "branding, forced sterilization, the Tuskegee experiment, or tasers." Dery posed the question, "Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?" Dery's 1992 answer was that one had to look outside the fiercely protected boundaries of the SF genre to find examples of this. Within SF proper, Afrofuturism's scope was, until recently, limited to a small number of practitioners. Dery could only name four African-American SF authors, including Octavia E. Butler and Samuel R. Delany, whose 1998 essay "Racism and Science Fiction" enumerates still relevant intra-genre problems. But examples of Afrofuturism can be found in disparate snatches from literature, popular music, and visual art: Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, Romare Bearden's collage work, the "pie-eyed, snaggletoothed robot" in Jean-Michel Basquiat's painting Molasses, and the various output of Jimi Hendrix, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and Herbie Hancock.

Over the past two decades, Afrofuturist discourse has expanded, and Ytasha L. Womack, author of this year's primer Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, has a much broader and deeper field to draw from. Authors such as Nnedi Okorafor and N. K. Jemisin explicitly write SF. Womack places Octavia E. Butler as one of the sides of her "Giza-like pyramid" of Afrofuturism, emphasizing her "central feminine narratives" as integral. DJ Spooky, Erykah Badu, and Grace Jones are amongst the plethora of cited musicians. A self-conscious and passionate fanbase has developed via Listservs, cosplay, and sites such as BlackScienceFiction.com. Womack posits contemporary Afrofuturism as challenging the nature of black art as only "washed in fatalism, southern edicts, or urbanized reality." Instead, Afrofuturism "inverts reality," offering a myriad of wormholes into alternate histories through which futures unbounded by trauma can be realized.

Kara Walker, Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching (2006). Painted laser-cut steel.

Just outside the entrance to the retrospective is a small pice by Kara Walker, Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching (2006). Black steel silhouettes in the style of Victorian paper panoramas assemble a confusion of violence and rape; even the setting, Africa or the antebellum South, is uncertain. Walker's method of heightening historical atrocity creates what Hari Kunzru recently referred to as an "endless carnival of cruelty that seems to be taking place in a sort of cultural Never-Neverland, somewhere between Gone With The Wind and hell." Walker and Mutu both produce ravaged, if dissimilar, figures. The latter's bodies have been invaded and taken over by color and texture, the former's utterly reduced to black shadow; all have been hyper-sexualized, though Walker's slaves have engorged genitals, not motorcycle feet.

Walker's statement that "a black subject in the present tense is a container for specific pathologies from the past" shows her intent: not to satirize slavery, but to focus only on the racist theories and caricatures invented to justify it, without offering any exit narrative. Womack mentions Walker only once in Afrofuturism, focusing on the "infamous nature" of her "harshly criticized work." It would be a misrepresentation to say Womack disapproves of Walker's approach, but it is certainly not the optimistic, transformative work which Womack wishes to emphasize. Mutu, who strangely goes without mention in Womack's book, exists somewhere between these two polarities. Her depictions of suffering and domination are subverted by the violent ecstasy of their imagining and her gestures toward alternate, unknown modes of life.

Science fiction necessarily speaks to the time of its creation, the author interpreting through distortion. This is exactly what Mutu accomplishes: her grotesques are our present.