Extract from Vertigo (1958).

As Slavoj Žižek and others have argued, the credit sequences designed by Saul Bass for Alfred Hitchcock's unofficial trilogy of late masterpieces—Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959) and Psycho (1960)—announce the visual motifs of each film and suggest their psychological underpinnings. The broken lines in Psycho are echoed in the slashes of the killer’s knife and the broken pathway from the Bates motel to the old Victorian cottage in which Norman lives, supposedly with his mother. The grid in North by Northwest mimics the Manhattan skyscrapers where Cary Grant’s dopey adman initially toils, as well the train tracks on which he travels as his identity is further and further confused and effaced, and the cornfield in which he famously ducks for cover under the attack of a faceless machine. The spirals that open Vertigo suggest the roads through hilly San Francisco on which Scotty pursues Madeline, the twist of her hair, the staircase that causes his eponymous vertigo to flare up.

Each credit sequence is echoed by the soundtrack of each film, all composed by Bernard Herrmann. The theme for Psycho is the famous staccato ee-ee ee-ee. North by Northwest is set to an interlocking, pulsating orchestra. And for Vertigo, Hermann lifted the most famous musical phrase from the Liebestod of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde: a rising and falling sequence that fails to ever resolve itself.

All of which suggests that Hitchcock—a famous tyrant—was actually, or also, one of the most canny collaborators of the 20th century.

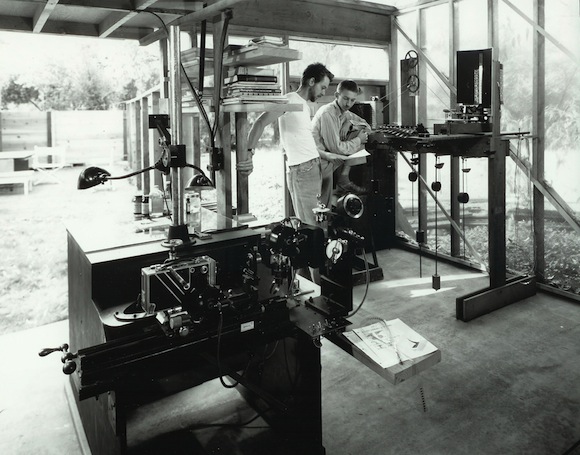

For the title sequence to Vertigo, Hitchcock had an additional, often unnoted, collaborator: John Whitney. A pioneer of computer animation who worked in television in the 50s and 60s and in the 70s created some of the first digital art, Whitney was hired to complete the seemingly impossible task of turning Bass’s complicated designs for Vertigo into moving pictures. A mechanism was needed that could plot the shapes that Bass wanted, which were based on graphs of parametric equations by 19th mathematician Jules Lissajous; plotting them precisely, as opposed to drawing them freehand, required that the motion of a pendulum be linked to motion of an animation stand, but no animation stand at the time could modulate continuous motion without its interior wiring becoming tangled.

John and James Whitney in their studio, c. 1943-1945. Courtesy of the estate of John and James Whitney.

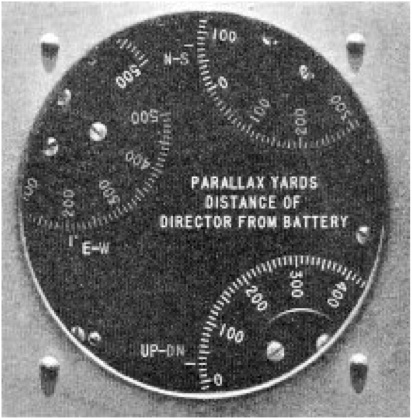

To solve this problem, Whitney made use of an enormous, obsolete military computer called the M5 gun director. The M5 was used during World War II to aim anti-aircraft cannons at moving targets. It took five men to operate it on the battlefield, each inputting one variable, such as the altitude of the incoming plane, its velocity, etc.

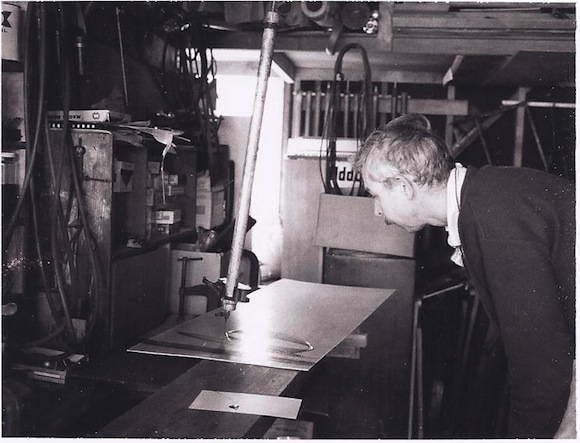

Whitney realized that the gun director could rotate endlessly, and in perfect synchronization with the swinging of a pendulum. He placed his animation cels on the platform that held the gun director, and above it suspended a pendulum from the ceiling which held a pen that was connected to a 24-foot high pressurized paint reservoir. The movement of the pendulum in relation to the rotation of the gun director generated the spiral drawings used in Vertigo’s opening sequence.

John Whitney drawing a Lissajous spiral, 1963.

The M5 weighed 850 lbs and comprised 11,000 components, but its movement was dictated by the execution of mathematical equations; it was very much a computer. Whitney’s work on the opening sequence for Vertigo could be considered an early example of computer graphics in film—and a clever détournement of military equipment.

Today is the 65th 55th anniversary of the release of Vertigo.