This marks the fifth and final installment in a genealogy of queer computing (Part One, Part Two, Part Three and Part Four).

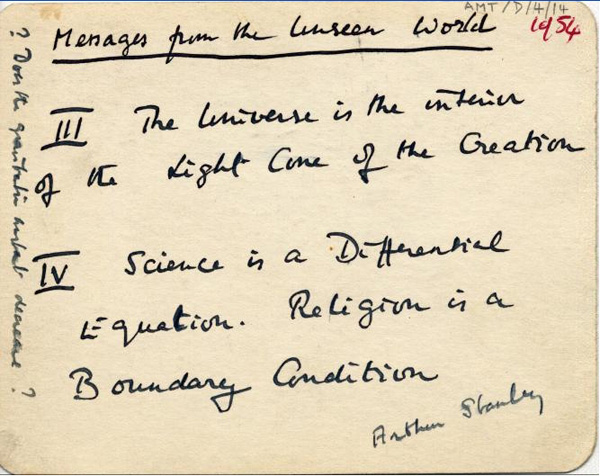

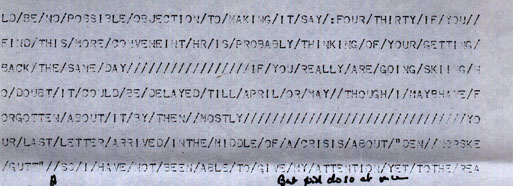

Note from Alan Turing to Robin Gandy, March 1954.

Born in London in 1949, Andrew Hodges attended Cambridge University from 1967 to 1971, where he trained as a mathematician. While there, he encountered the work of Alan Turing for the first time, learning of his significant contributions to the history of mathematical logic—though not of his homosexuality.

During his last year at university, Hodges came out openly as a gay man and became an organizer for the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE), which continued the gay rights struggle after homosexuality was largely decriminalized under the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Upon graduating he moved to London and became involved in the then-nascent Gay Liberation Front, where he met several other activists and co-authored a number of gay rights manifestos.

The first manifesto was a polemic against the treatment of homosexuality as a psychological disorder, authored anonymously with four other activists—Geoffrey Weeks, David Hutter, James Atkins, and Nick Firbank. Hutter was the long-term partner of Atkins, who had been Alan Turing's first lover from 1933 to 1937. It was during this collaboration that Hodges learned of Turing's sexuality and the role it played in his tragic death, as well as the psychological and chemical “treatment” he endured as part of his sentence for gross indecency. The story of these final years of Turing's life informed the writing of the manifesto; as it exemplified the tragic and inhumane treatment of gay men and women by psychological institutions that the group hoped to convey.

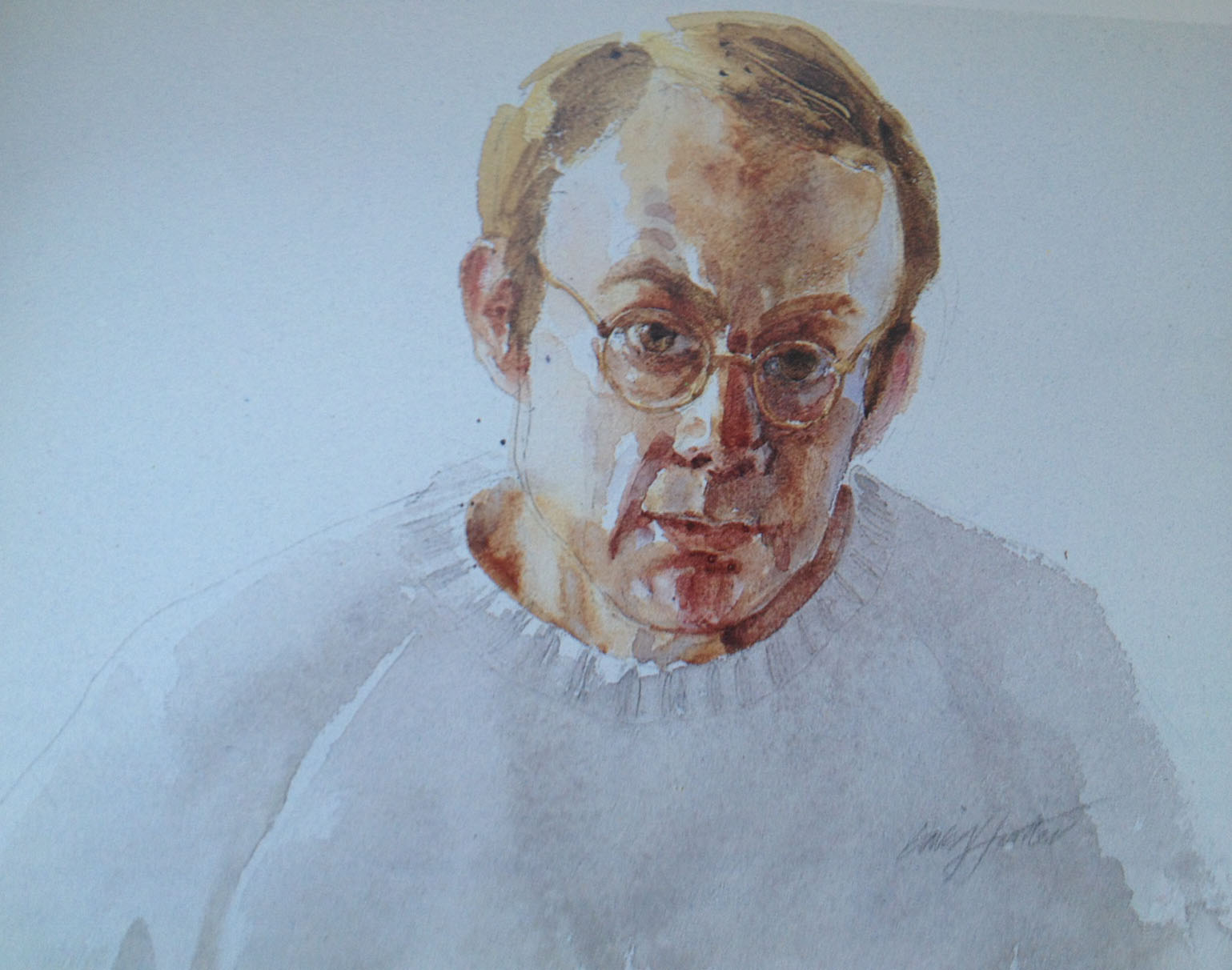

Self-Portrait by David Hutter ca. 1984.

Hodges’ second book was even more ambitious. Co-authored with Hutter and written between April 1973 and April 1974 while Hodges was a graduate student in London, With Downcast Gays: Aspects of Homosexual Self-Oppression (1974) elaborated on the concept of self-oppression as a barrier to gay liberation (previously promulgated in the 1971 Gay Liberation Front Manifesto), stating that "The ultimate success of all forms of oppression is our self-oppression. Self-oppression is achieved when the gay person has adopted and internalized straight people's definition of what is good and bad."[1] Self-hatred was viewed as the means through which homosexual men and women were kept oppressed. Internalizing the idea that homosexuality is wrong, refusing to acknowledge existing oppression by heterosexual society, experiencing self-doubt at homosexual thoughts and actions and maintaining polite silence with regards to homosexual life are all means of self-oppression, which was seen as the primary barrier to forming a collective gay community capable of enacting radical change.[2]

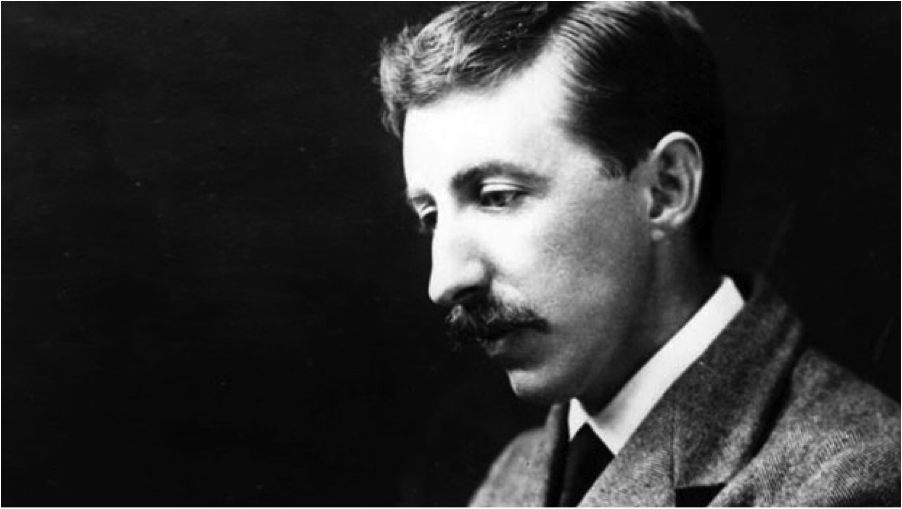

A large section of the text is devoted to E. M. Forster, the famed English writer and, along with other familiar figures such as Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, member of the Bloomsbury group. Titled "A Case in Point," the chapter deals with Forster's refusal to publicly acknowledge his sexuality publicly, portraying it as a shameful betrayal of his insistence on the value of freedom, individual commitment, and above all personal honesty.

Perhaps Forster's most famous remark was that if he were forced to choose between betraying his country and betraying his friends, he hoped he would have the courage to betray his country. Since the choice was unlikely ever to be presented, this was an easy, if startling, claim to make. The real choice for Forster lay between damaging his reputation and betraying his fellow homosexuals. Alas, it was his reputation that he guarded and gay people whom he betrayed.[3]

This betrayal is made all the more jarring by the posthumous publication of Maurice, a novel written by Forster in 1914 with not only a homosexual theme, but a happy ending, something unheard of in most literary depictions of homosexuality at the time. The finished novel had been circulated among homosexual critics and friends of Forster for decades. The author's sexuality was an open secret, but no one would step forward to acknowledge its existence. Hodges and Hutter lament the damage that could have been prevented had he come out publicly later on in life, during that crucial, formative period for public opinion and critical legislature on gay rights. Even the earlier publication of Maurice could have done a great deal to upend the assumption that queer narratives and queer lives must ultimately end in a tragic death or suicide. "So readily does the gay community accept that homosexuality is a secret and individual matter that Forster took it for granted that his privileged status as the Grand Old (heterosexual) Man of English Letters would never be threatened by the public revelation of his homosexuality by any of those gay people who confidentially knew of it," they wrote.[4]

E.M. Forster.

Hodges and Hutton were writing at the height of the debate within the gay community over the importance of both coming out and of outing others, an impulse so central to the struggle of the GLF that it is the title of their first publication on November 14, 1969. It is in this moment that Hodges felt compelled to tell the story of Alan Turing, and in 1977 he began extensive research into all aspects of Turing's life. The resulting work, Alan Turing: The Enigma, was published in 1983, and it is the first public account of the full life of Alan Turing as both one of the most important figures of the 20th century and an openly gay man. It was a break from the culture of discretion that otherwise pervaded the polite society of homosexual self-oppression in the UK. For Hodges it was an attempt to move away from the compartmentalization of life, of the separation of the emotional from the technical. It was a conscious assertion that gay life, experience, and feeling should not be omitted from the writing of larger histories.

In March of 1954, three months before his death, Alan Turing sent four postcards to his friend and confidant, mathematician and logician Robin Gandy (discussed in Part Four of this series), labeled "Messages from the Unseen World." Cryptic and vague, they can be interpreted as coded messages regarding Turing’s thoughts toward the development of physical cosmology, the origins of the universe, science, and religion. Some remain indecipherable, referring to some phrase or concept Turing never elaborated on. Each message is also quite beautiful, even poetic:

III. The Universe is the interior

of the Light Cone of the Creation.IV. Science is a Differential

Equation. Religion is a

Boundary Condition.V. Hyperboloids of wondrous Light

Rolling for aye through Space and Time

Harbour there Waves which somehow Might

Play out God's holy pantomime.[5]

According to Hodges, "the reference to 'the unseen world' was a shared joke with Robin Gandy about the religious standpoint of the mathematical physicist and astronomer Arthur Eddington, whose book The Nature of the Physical World had started Alan Turing thinking about fundamental physical theory in 1930. It was a parody of the hymns of Sherborne School chapel, but perhaps also a serious reference back to his first wondering about mind and matter."[6] Whether intentional or not, the messages also seem to evoke the unseen world that Turing occupied and was only able to fully share in coded exchanges with close confidants such as Gandy.

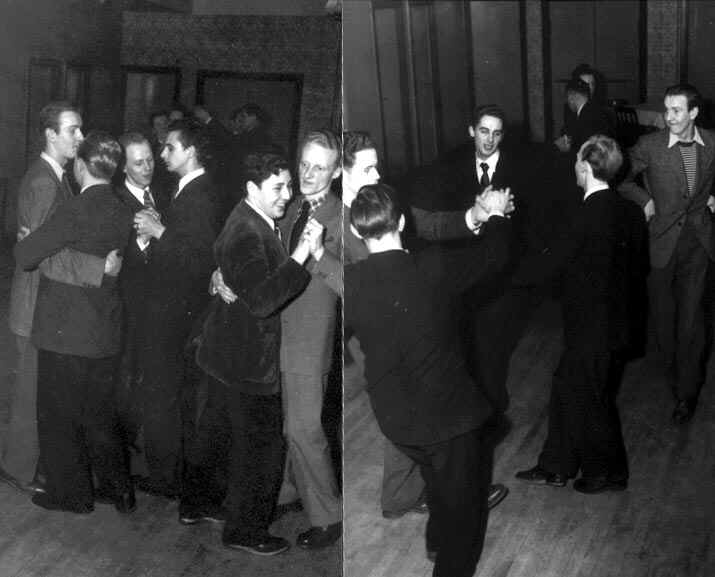

Photos of "for men only" dances in Norway, ca. 1952.

Far from being "unseen," Turing was under constant suspicion and surveillance by the police toward the end of his life. He was viewed as something of a security risk, particularly because he frequently traveled internationally to France and Scandinavia in search of a more open and tolerant environment. He had initially been attracted to Scandinavia after hearing rumors of dances taking place there "for men only," photos of which had been published in the local press. These were events organized by Forbundet af 1948 or F-48, Denmark's first gay rights association founded on June 23, 1948. By the early 1950s the organization had expanded to over 1300 members and had chapters in Norway and Sweden.[7] Inspired, Turing became interested in learning Danish and Norwegian, and even met a young Norwegian man named Kjell, after whom he would name one of his final computer programs.

In March of 1953, Gandy was preparing to submit his PhD thesis in Cambridge, and made arrangements with Turing for its defense some time in April. Rather than write a response by hand, Turing typed a letter on the Manchester Mark I, the same machine used by Christopher Strachey as described in Part Three of this series. He printed it out, and posted it to Gandy. In it he notes that "Your last letter arrived in the middle of a crisis about 'Den Norske Gutt' so I have not been able to give my attention yet…" While it isn't entirely clear just what this crisis may have been, it seems that Kjell had recently arrived in Newcastle from Norway, but since his conviction of Gross Indecency in 1952 (see Part One) Turing had been under police surveillance, with officers posted outside his home. In this context, the arrival of a foreign visitor was viewed as a potential security leak, and officers were deployed all over the North of England to intercept Kjell.[8] At this point in his life, Turing's accomplishments had become more of a burden than an asset, as his knowledge of the British nuclear program made him a high security risk. As such his movements and activities were closely monitored, and his relationship with the police ("the poor sweeties," as he called them) were increasingly frayed. Yet despite being deprived further access to government resources, and despite increasing surveillance and police suspicion, Turing seems to have continued working on a set of experimental ideas that, apart from a few allusions in letters to Gandy and others, are entirely lost.[9]

Message from Turing to Gandy, printed off the Manchester Mark I, ca. 1953.

Toward the end of his life, Turing decided to undergo Jungian analysis, writing down all his dreams in a series of three journals. Upon his death his psychiatrist Franz Greenbaum lent the books to his brother, John, as a means of clarifying Alan's mental state leading up to his suicide. John found the material deeply disturbing, particularly Alan's characterization of their mother and the descriptions of his homosexual experiences, beginning in adolescence.[10] The journals were destroyed shortly after being returned to Greenbaum.[11] Hodges describes a similar experience, of having viewed a document in 1978 in which Turing describes a number of men he met while vacationing in Corfu, Athens, and Paris in the summer of 1953, but which was subsequently destroyed by what he describes as "a censorious employee of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment."[12]

This series is a tenuous history in no small part due to efforts to make it so through the removal of material from historical record, even when done with the presumed interests of the figures at hand. The exclusion of queer life from history often leads to its erasure and disappearance. As Ann Cvetkovich argues in An Archive of Feelings (2003), it is documents such as Turing's journals that demonstrate:

The profoundly affective power of a useful archive, especially an archive of sexuality and gay and lesbian life, which must preserve and produce not just knowledge but feeling. Lesbian and gay history demands a radical archive of emotion in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love, and activism, all areas of experience that are difficult to chronicle through the materials of a traditional archive. Moreover, gay and lesbian archives address the traumatic loss of history that has accompanied sexual life and the formation of sexual publics, and they assert the role of memory and affect in compensating for institutional neglect.[13]

The insistence on not only the importance but broad relevance of an affective sexual archive is fundamental to this history.[14] Thus, this is not a reinterpretation of history, or a queering of computation. Rather it is an insistence on the queer as it exists and has always existed within them.

[1] Hodges, Andrew and David Hutter. With Downcast Gays: Aspects of Homosexual Self-Oppression. (1974) <http://www.outgay.co.uk/wdg1.html>

[2] It is surprising just how much of the text remains relevant and true forty decades later, and it is deserving of a much deeper analysis and historical framing with regards to gay rights movements in the UK in the 1970s.

[3] Hodges and Hutter (1974) < http://www.outgay.co.uk/wdg4.html>

[4] Ibid. (1974)

[5] Hodges (1992) p. 513

[6] Hodges (2000) <http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/wondrous.html>

[7] This openness would not last long, and in 1955 authorities cracked down on F-48 with arrests and show trials. Despite this the organization continued on, and in 1985 became the Danish National Association of Gays and Lesbians (Landsforeningen for Bøsser og Lesbiske, Forbundet af 1948 or LBL).

[8] http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/wondrous.html

[9] There is a great deal of speculation on what Turing may have accomplished had his life not been cut so tragically short. See: Hodges, Andrews "What would Alan Turing have done after 1954?" Lecture at the Turing Day, Lausanne, 2002 <http://www.turing.org.uk/philosophy/lausanne.html > and Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfood "On Alan Turing's anticipation of connectionism" Synthese Volume 108, Issue 3, 1996 pp 361-377.

[10] http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/06/22/alan-turing-s-brother-he-should-be-alive-today.html

[11] Hodges, 491.

[12] http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/wondrous.html

[13] Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press (2003) p. 241.

[14] The relevance of such an archive can be seen in the way Turing’s sexual relationships found their way into his programming work, as in the case of Kjell, and in the fact that his ideas often survive only through his correspondence with fellow queer colleagues, as in the case of Gandy. Yet in spite of the clear relevance of personal experience to broader technological developments, the archive of queer computing is often found to be troubling by its caretakers, who choose to bury, edit and destroy until this affective power is diminished.