Thomas Hirschhorn, Bootleg extract from Touching Reality.

Yesterday, Engadget and other outlets reported that the USPTO made its final decision to nix a patent filed by Apple in 2007 in an attempt to claim intellectual ownership of a number of touch-screen gestures, including the two-finger "pinch-to-zoom." Melissa Grey reported that "According to documents filed by Samsung in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California on Sunday, [the patent] was found wanting by the USPTO due to it being anticipated by other patents and declared otherwise non-patentable."

Patent number 7,844,915 has the unusual distinction of earning coverage in Artforum, in an article written by Alex Provan this past March. Provan drew a chilling picture of a world in which interaction with images took place according to a strictly programmed repertoire of movements:

Apple has filed patents for Pinch-to-Zoom, Slide-to-Unlock, Multifinger Twisting, Double-Tap-to-Zoom, and Over-Scroll Bounce, aka Rubber-Banding, among other functional finger gestures. The company is indisputably striving to corner the market on how we move our fingers across screens, how we scan and massage images. This was evident in August, when Apple won a major copyright-infringement lawsuit against Samsung and was awarded one billion dollars in damages, bringing us closer to the apocalypse Steve Jobs augured a few years ago in his Herman Kahn–inspired attack on Google’s Android OS: “I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this.”

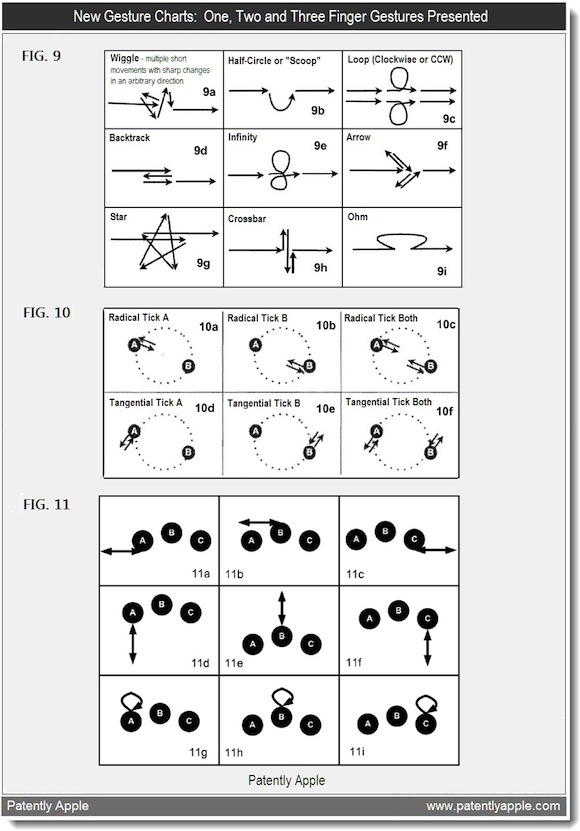

Perhaps we're a step further from that apocalypse today (although it's worth noting that the denial of the pinch-to-zoom patent was first floated in December, well before Provan's article). Nevertheless, the US ruling does not challenge the underlying principle that gestural movements may be patented. Apple still has a number of patents in place relating to touch-screen gestures. Some of these can be seen in the following diagram published by the website Patently Apple as a summary of Apple's applications:

It's unclear when we'll be seeing these particular multi-touch gestures roll out. So far, they remind me of JODI's Untitled (mobile app), in which iPhone users must follow an absurd choreography of gestures dictated by their handheld device. When they complete a meaningless task correctly, they are rewarded with the ringing of an alarm. It looks like this:

ZYX ________/n8 from JODI.

Like JODI, Provan takes a dim view of the regulation of user behavior by technical devices, arguing that "Apple’s patented finger routines risk unsettling the delicate balance between managing the body and promising users unparalleled freedom and expressivity." In other words: are you programmed, or are you being programmed, by your devices?

In his article, Provan cites recently-departed computer pioneer Douglas Engelbart as an important precursor to today's gestural interface wars. He wrote, "Engelbart argued that computers should 'augment human intellect' and conceal their own complexity in order to help us solve 'the big problems'; here, finally, was a machine [the Apple Mac] that did just that." In fact, Engelbart was no great advocate of making computers overly user-friendly; saying that he intended to conceal the complexity of computers is a bit unfair. Moreover, he was "mildly appalled" by the Apple Mac. As Bret Victor points out in this article, the technologies pioneered by Engelbart have all been implemented in ways that did not reflect his intent, and in the wake of his passing, in the midst of patent imbroglios over human-computer interaction, it's well worth revisiting Engelbart's ideas, and the 1968 demo.

During that demo, Engelbart presented one innovation that never quite took off: a chorded keyboard. The keyboard was an input device which, with only five keys, replaced all of the functions of a QWERTY keyboard. It's essentially a multi-touch interface; users type particular characters by pressing certain combinations of keys, or chords. Essentially, it is asking the user to replace the one-key-at-a-time model with a multi-touch typing system. Interestingly, studies have shown chorded keyboards to be superior to QWERTY keyboards in a number of ways, but the complexity of using them kept people away. The 1983 article "The QWERTY Keyboard: A Review" described the situation as follows:

Rearranging the letters of the QWERTY layout has shown to be a fruitless pastime, but it has demonstrated two important points: first, the amount of hostile feeling that the standard keyboard has generated and second, the supremacy of this keyboard in retaining its universal position...The design and the layout of the QWERTY keyboard are not optimal for efficent operation...

I can't help but think about this when reading Apple's rationale for the Star and the Crossbar and all that:

But existing methods for real-time user interface input gesture alterations and modifications are cumbersome and inefficient. For example, using a non-contiguous sequence of gesture inputs, with at least one gesture to serve as a behavior modifier, is tedious and creates a significant cognitive burden on a user. In addition, existing methods take longer than necessary, thereby wasting energy.

The complicated gestures outlined in Apple's multi-touch patent perhaps share something in common with Engelbart's chorded keyboard; they may have a difficult time convincing users to adopt any gesture more complicated than the three-fingered swipe. Perhaps the gestural patents that are the most troubling are not those that attempt to manage users, asking them to learn complex behaviors in order to use their devices more efficently; the most troubling are those that attempt to stake a claim over our existing repertoire of movements.