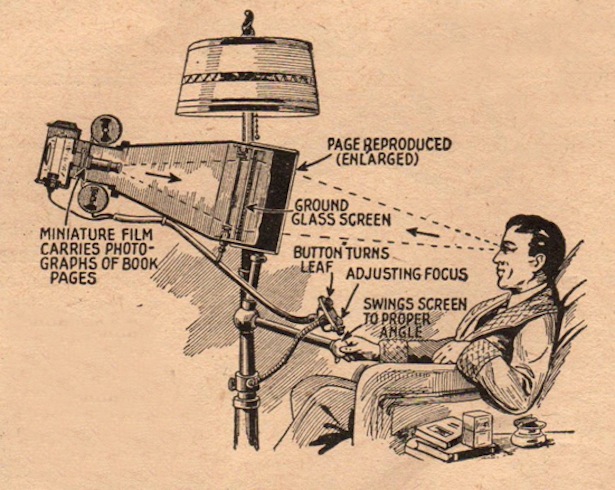

Image via Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1864 from Everyday Science and Mechanics magazine, 1935

Artists have often been at the forefront of technological innovations in publishing media — experimenting to push boundaries in new directions. They create new ideas about interactions with emerging media and spark fresh conversations about legacy practices and formats — think; David Horvitz, Metahaven, and Paul Chan’s Badlands Unlimited, to name only a few. This phenomenon of experimental publishing isn’t new, but Alessandro Ludovico puts the enterprise into a unique and digestible perspective in Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1864. His research reveals the deep history and early seeds of current publishing media remix in their original surroundings — from Fluxus promotions to the rise and fall of zines and up to the interventionist work of Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev’s Newstweek and beyond.

In our present digital era, the ‘death of paper’ has become a plausible concept, widely expected to materialise sooner or later. The ‘digitisation of everything’ explicitly threatens to supplant every single ‘old’ medium (anything carrying content in one way or another), while claiming to add new qualities, supposedly essential for the contemporary world: being mobile, searchable, editable, perhaps shareable. And indeed, all of the ‘old’ media have been radically transformed from their previous forms and modalities – as we have seen happen with records, radio and video. On the other hand, none of these media ever really disappeared; they ‘merely’ evolved and transformed, according to new technical and industrial requirements.

The printed page, the oldest medium of them all, seems to be the last scheduled to undergo this evolutionary process. This transformation has been endlessly postponed, for various reasons, by the industry as well as by the public at large. And so the question may very well be: is printed paper truly doomed? Are we actually going to witness an endless proliferation of display screens taking over our mediascape, causing a gradual but irreversible extinction of the printed page?

It’s never easy to predict the future, but it’s completely useless to even attempt to envision it without first properly analysing the past. Looking back in history, we can see that the death of paper has been duly announced at various specific moments in time – in fact, whenever some ‘new’ medium was busy establishing its popularity, while deeply questioning the previous ‘old’ media in order to justify its own existence. In such moments in history, it was believed that paper would soon become obsolete.