Chimera Q.T.E at London’s Cell Project Space draws its curatorial theme from a collagist interpretation of the Internet – a view that sees the web as a collection of orphaned, mashed and re-mashed digital fragments, or a kind of infinite patchwork quilt. For inspiration and the exhibition title, London based curator Attilia Fattori Franchini nudged aside contemporary similes to pull a monster from Greek mythology. The chimera, like that other Grecian mashup the griffin, is a beast composed of several animals, and both its status as an organic mishmash, and the common use of its name to denote fanciful pipe dreams, provided Franchini with a comparative reference for what the web is like.

Luckily the beast’s double status as a hybrid creature and linguistic unit is also a useful tool for interpreting the show. For while the fragmented web model (i.e. the body of the beast) is popular and necessary for those who see contemporary artists as nomadic remixers and postproducers (see Mark Amerika’s recent remixthebook), it is an idea built on fragile conceptual foundations that tumble down beyond the aggregated world of Tumblr and BuzzFeed. Hence the idea that today’s artists are cut-and-pasting their way towards a liberatory new praxis could be mere chimera. What Chimera Q.T.E captures then is not a mediation of the Internet as it is – because nobody really knows. It captures an aesthetic sensibility informed by the fragmented web model and its proposed utopic possibilities. When formalised this sensibility, shared by the eight international artists on display, becomes a hybrid mix of lurid color palettes, errant geometry, and vivid, startlingly flat, digital precision. What the viewer sees in each work is essentially a dispatch from an abstract digital territory, an ambient landscape of the hyperreal.

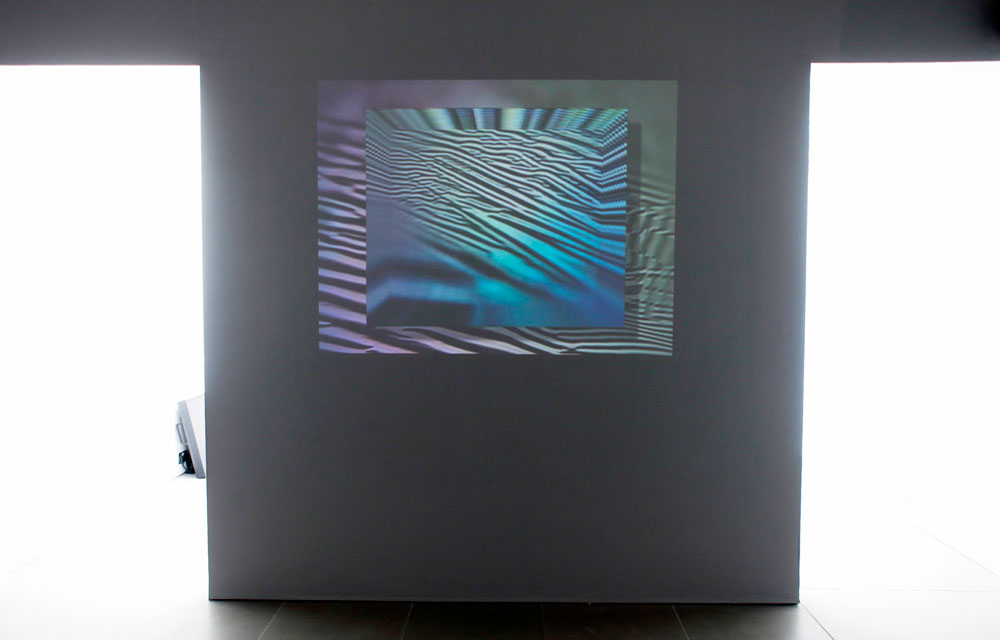

Chimera Q.T.E installation view

Montreal-based Sabrina Ratté’s nine minute looped video Age Maze (2011) offers a hypnotic view of this alternate expanse. It is a shimmering kaleidoscopic journey through a field of shifting planes and dissolving geometric shapes. With its ambient soundtrack and trippy triangle animations, the work offers easy comparisons to the lo-fi, New Age aesthetics favoured by those affiliated with chillwave or seapunk, but something far more disquieting and primal is at play in Ratté’s piece. In his 1970 book Migraine Oliver Sacks introduced the idea of the migraine aura, a symptom of the condition that resulted in pre-headache visual hallucinations for the sufferer. He wrote ‘the simplest hallucination takes the form of a dance of brilliant stars, sparks, flashes or simple geometric forms across the visual field’. These hallucinations, which Sacks suggests were recorded as early as the twelfth century, are the first instances of geometrical abstraction and parts of Age Maze bear a striking resemblance to the disorienting phosphenes that cloud the vision of migraine aura sufferers.

Age Maze, Sabrina Ratté, 2011

A similar affinity can be seen in New York- based Travess Smalley’s Alta Dark (2012) a large abstract digital print on silk in which warm pinks, reds, and greens coalesce in shards and swirls of amorphous color gradation. One gets the sense in looking at both works that the surface of abstraction is in fact obscuring a coherent image laying just behind it. Whereas parts of twentieth century abstraction (i.e. Mark Rothko, Morris Louis, and Jackson Pollock) may be said to evoke a transcendental signified, Smalley and Ratte’s works conjure the transcendentalism of the unexpected vision that obscures reality. Their language of abstraction may have clear cultural antecedents, but the dual sensation of disquiet and disorientation the works provoked felt thrillingly unique. Elsewhere, London-based Oliver Sutherland’s Waving (2012) registered a muted form of abstraction. Two flat LCD screens were positioned on the floor and propped against the wall next to each other. On each screen the area of what seemed like dappled and clouded glass was illuminated by a light that was blurred by the partially see-though material’s surface. Sutherland’s seemed to be a more lyrical impulse, a poetic meditation on a human gesture diffused.

Alta Dark, Travess Smalley, 2012

In the centre of Cell’s modest white cube is Adam Faramawy’s Violet Like Psychic Honey 2 (2012) a two screen sculptural installation whose ambient, Vangelis-like soundtrack both dominates the room and blends with synthesised chords drifting from Ratté’s separate projection space. The screens sit on two spray-painted plinths whose gradated colours look like details from an HTML colour spectra wheel. Faramawy’s video also deals in abstract space, but is closer to that of the looping world of desktop screensavers. On each screen animated footage cycles through images of crystal formations, glitched imagery, organic shapes and rippling water oscillate against flat washes of too perfect digital color. Again there is a disconcerting air, but this time it comes from the banality of the desktop loop, and the planeless territory of a post-human digital expanse. Still photographs in Berry Patten’s *D (2012), The Dream is Kournikova (2012), and Cornelia Baltes Baccara (2012) also tread the same digital path faultlessly flat imagery, and so it is left to fellow Londoners Jack Lavender and Nicholas Deshayes to rough things up a bit in the material world. Both artists use steel in their sculptural assemblages. Lavender’s Glasses Tree (2012) is a small tree-like sculpture with mirrored shades hanging on each barren branch, and Deshayes' Salts (2012) is a multi panelled wall-based structure. Both works look as if they’ve been shanghaied from the industrial set of a 90s cyberpunk flick or the studios of Josh Harris’s Pseudo.

Violet Like Psychic Honey 2, Adam Faramawy, 2012

Chimera Q.T.E is a curious exhibition. Attempting to capture something of the heterogeneity of the Internet, Franchini has instead produced a display that foregrounds the aesthetic sensibility shared by a group of international peers. Together this collection of works yields an experience for the viewer that skims, perhaps ironically, across a surface of cultural nostalgia and transcendental spiritualism. While this is too partial a view to be representative of what the Internet is, it provides an indication of where the fragmented web model, and the utopic image of the artist as postproducer, is currently pushing abstraction and digital aesthetics.