The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have developed a significant body of work engaged (in its process, or in the issues it raises) with technology. See the full list of Artist Profiles here.

"In the distance I see Kimmo Modig. He's walking around Helsinki with his iphone, grumbling about bad art."

Antagon 2013: Proceedings (2013)

Age: 32

Location: Helsinki, Finland.

Jesse Darling: How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

Kimmo Modig: I remember doing sound collages with boomboxes in my early teens, you know, like having two of them playing something I’d recorded earlier as a backtrack while the third one recorded whatever I was doing live on top of that. I’d repeat this process again and again until the signal-to-noise ratio was heavily weighted towards noise. But already at that time I always wanted to use my voice, to have a narrative of sorts. I’ve lately been returning to a way of being that I had in my teens, when I was dressing to provoke and performing nude on stage with my childhood friends.

Later on I got into so-called experimental music, and started directing a Helsinki-based organisation called Äänen Lumo (Charm of Sound) between 2008–2011. Nowadays I feel detached from any kind of hacking / DIY / circuit-bending activity. I still get really excited about adventurous music—for example, Bee Mask has blown my mind so many times. Mostly, though, I just listen to the Soundcloud stream—I usually like whatever Jennifer Chan reposts.

I’m increasingly drawing on my background as a sound designer in my work, and I think there will be more of this in the future. I still follow the discussion around sound art, and look for a new, unexpected way to understand it, maybe as a Trojan horse—a tool for artistic expression and as a personal methodology. One of my fave books of late has been Black Sound White Cube by Ina Dieter and Wudtke Lesage, which looks at why Sound Art is predominantly white noise without rhythm. I think someone like Phill Niblock (the godfather of drone music) is very anti-culture, you know, in not wanting to communicate anything with music, in keeping it free of conventional structures such as melody etc. The future of sound in art is in naivety, not surround.

JD: Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I did an MA in sound design at the Theatre Academy, Helsinki. I must stress here that we weren't taught to be technicians but "artist-designers" who dabble with installations, music, collaborative practices and contemporary theatre & performance art. I didn't really click with that many people in school, so I ended up graduating without belonging to a scene or any newly formed company etc. My whole artistic career has been about moving from one scene to the next. I don't have any kind of cohesive or even formative knowledge of anything but just scatter from everywhere.

JD: What does your desktop or workspace look like?

KM: I share a studio with two sound designers and a poet in North central Helsinki. I pay €120 a month. It's more like an office, but luckily there's a recording booth here which is really important for me. My desktop is nothing special I imagine. I mostly use Ableton Live, Premiere, Writeroom, Chrome, and an internet-connection-killing app titled Freedom.

Modig remembers Anatagon's artists before the biennale in a place that doesn't exist anymore.

Remembering Antagon: Artists are mountains (2013)

JD: What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I do a lot of things, I suppose, like teaching and DJing and whatnot, though for 2013 I'm on a grant from Kone, a private Finnish foundation. Then there are grants with which I fund projects like Antagon (a biennale I founded in Turku, 2013). I used to be the director for this gallery Titanik for a year; I earned €1500 per month in a 25h/week. That was pretty good, though it was mostly paperwork, which I found frustrating. A big problem in the art world, at least here in Finland, is that nobody is trusted to make real decisions, so all the good ideas and radical energy get killed by faceless boards and committees.

This is a larger issue and it has to do with attempts to hide taste behind politically correct and credible power structures. This is very difficult to do with something as meaningless or at least hard to measure as contemporary art. To think that art is just for lulz in a world full of unfathomable suffering and constant exploitation is hard and some might say, unethical. In order to avoid these issues, we’ve created these value systems, complex ever-changing hierarchies, which are ultimately ways of proving that art matters. When I work with institutions, I try to always work directly with individuals, so I know that there's someone who hopefully understands what I'm trying to do.

JD: Do you think these professional friendships are like, part of the job?

KM: I don’t know, are they? Is the work also a barrier reminding us where one singularity ends and another begins? I think the best way to understand someone begins with grasping the power relations at play. Like I don’t know if I’ll ever understand you, which is strange because our works (yours and mine) are so much about ecstatic communication. The art world creates and accelerates so much paranoia and amnesia and discontinuation in relationships. To survive in an art world that is constantly afraid of its own emptiness, everybody has to have an agenda. I've never had one. To be able to take this stance talks volumes about my privileged position, of course, but I’m a total nihilist without any ethical reverberating chamber. The Groys article on change and the avant-garde meant a lot to me.

Stills from the trailer for the Suomen Paviljonki / Finnish Pavilion

JD: That makes sense, though I find your approach full of contradiction (which, knowing you, might be deliberate). You talk about the emptiness of the art world; you say art has no inherent meaning, and yet in your curatorial projects and your auxiliary works you seem to want to produce or harness spaces of authenticity or intersubjectivity. Like you want to work with individuals, not institutions; you produce these performances that mess with the conventions of playing to or not playing to an audience (but which would be meaningless without it); it’s like your project is all about lived experience, and you’re trying to communicate that to another; singular or plural.

KM: I wouldn't say what I do is about authenticity. I’m trying to bring people and things together, play host to a situation. It's easy to point out either way, i.e. how artificial or authentic it was, for example, having you or Maja Cule or anyone hanging around in Turku during Antagon. Like it’s sort of a forced meeting, but you can enjoy it tremendously, go past that, communicate. I think things get as real as one lets them, you know? Like, look, here’s a situation: if you invest in it maybe something will happen, but if you don't, at least there's glorious art works that you can also enjoy passively just by being there.

JD: In post-net politics and aesthetics there's a lot of discourse about the legacy of the network and how it has affected our aesthetic and sensibility, our sense of space and place. In this context I want to talk about your work as a seer, using intuition and “magical thinking” to create a space of exchange between you and another where data flows take place in the form of card readings. Do you relate to the techno-utopian idea of "the cloud" or noosphere, like the collective consciousness? Are you consciously channelling this?

KM: The idea of a noosphere seems a bit far-fetched for what I do, which is to try to feel signals coming from the person(s) sitting opposite me. It’s mostly just social skills: focusing, noticing the details, listening to what they’re saying (with or without words). Sure, I can refer to things most of us might have in common: life's big questions, relationships, work. When I did the reading at V4ult gallery in Berlin, I had 10 minutes per person and I just trusted my intuition about people and talked about things I felt might resonate with them. From there on out, it's a matter of luck, faith, and in most cases, genuine non-verbal dialogue. Mostly people come looking for affirmation of decisions they think they’re about to make, although usually they've made the decision already.

JD: Can you tell me what I'm thinking right now?

KM: No, but if I can be selfish and assume you're thinking about me, then I'd imagine you're thinking about my not having any goals, which seems to bother you. I know you have your very personal issues with Buddhism, but I actually believe in the idea of inner peace which should be something unshaken by everyday defeats and victories. Since we can control so few things in life, having long-term goals other than happiness just seems silly.

JD: As someone whose work is so much about liveness, contingency, relationships and networks, how do you negotiate the flatness ("deadness"), and/or the object status of the document?

KM: I didn't document my works for a long time, mostly because I didn't think this would be a career of any sort, and because I was invested in so many different things. Nowadays I do like to document my work, but I feel like it's a project you have to figure out every time anew. Sometimes the best documentation is the rumour and sometimes you really need to hire a camera crew. I directed a prologue and an epilogue for Antagon, which were conceived as celebrations of the Antagon vibe, rather than straightforward information about the event. When I made the Sounds Like Work event with Jenna Sutela (in Kiasma museum, Helsinki, 2012), it took us 10 months to put together a short documentary video, I guess because our conception of what the event was really about kept changing radically after the event. For me, Sounds Like Work (which featured e.g. Bill Drummond, Miriam Katzeff, Minouk Lim, Jaakko Pallasvuo and Anneli Nygren), was the beginning of something real. It was my blueprint for a practice fusing event production, curation, dramaturgical thinking, and performing. We had a slogan, “Make Poems Not CVs”, and we really tried to figure out how to do everything as freely as possible within the event production: we tried to figure out how to make the production into an artwork an sich. It wasn’t a total success, but it put me into motion for good.

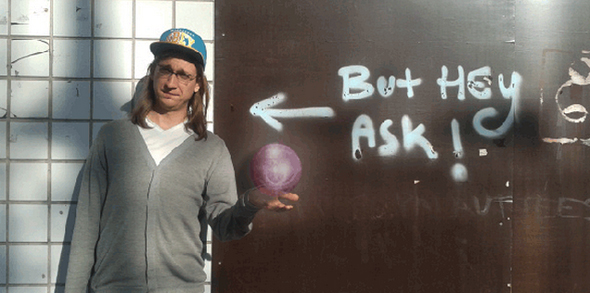

Death of You (2013)

JD: Though we talk a lot about post-internet, I sometimes feel like one of the biggest things we have to contend with in contemporary practice is the legacy of relational aesthetics—the deskilling of art practice, "just doing stuff", and not trying to make it mean anything, like, in the unfashionable modernist sense. I feel like your practice is a post-relational practice in that it happens in real time and space, but without the "whatever" aspect of some relational aesthetics shit. You’re gonna hate me for saying it, but it's almost as though you are trying to force meaning into meaninglessness—how else would you describe someone who calls themselves an “oracle?”

KM: I agree. That desire to force meanings comes from my background in theatre, where you might have a group of people trying to figure out these impossible conversions, such as how to turn the pain of the mother into a soundscape, or how to create lighting design that has something to do with current governmental policies or whatever. Anyway, I accept that the stuff I do is mostly madness and meaningless and then I make a big point out of it. I mean either we dig craftsmanship and the certainty it brings or not. And I absolutely don't.

JD: How do you select your collaborators or (as a curator) your artist/projects?

KM: Well, there has to be trust, and it should feel exciting. For example, this collaboration with you (if you can call it that) began in Venice 2013, with a chance introduction: I proclaimed on Twitter that I’d be doing card readings, and you wanted one. We dodged our pre-set dates but ended up doing readings for each other in this desolate part of the island one hour before I had to leave for my flight. It was a clash of two seers. I think I decided I want to work with you when you refused to hug me when we parted ways, saying “we're colleagues not friends”. I’m trying to establish this new profession of dramaturge slash curator, and look at everything as an event or performance, striving for a dialogue or a polylogue between people with wildly different aims while keeping an eye on the structure of the events taking place. I guess what I'm doing is I'm performing art, really.

JD: Performing art? Like performance art? Or like, performing the act of making art?

The latter. All show, but the kind that makes you cry.