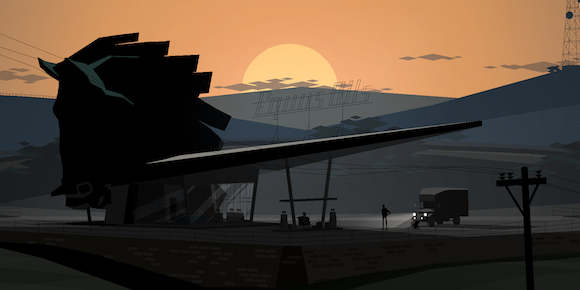

Still image from Cardboard Computer (Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott), Kentucky Route Zero (video game). Act I, Scene I: Equus Oils.

"I've got a delivery on Dogwood Drive, but I'd rather watch the sunset." –Conway, Act I, Scene I

Kentucky Route Zero, created by indie developer Cardboard Computer (Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott) is, so far, a well-polished crystal that shimmers out of the otherwise looming darkness of the video game industry.

So far, that is, because the game is intended to be released episodically in five "Acts," of which only the first two are currently available. Acts I and II are written superbly, with simple yet often deeply poetic tenor. Their art direction is first rate, blending Brechtian staging with De Stijl modernism. The game play is also a unique hybrid of familiar point-and-click adventure interface and engrossing interactive dialog. In the initial episodes, Kentucky Route Zero is a tranquil fantasy, a beautiful, haunting, and contemplative experience—adjectives one gets to use all too rarely when talking about video games.

The game revolves around a cast of characters who collectively are trying to find a place that feels like home. Players primarily navigate the game as Conway, a soon-to-be-retired delivery truck driver on his last delivery to a seemingly unknown address on Dogwood Drive tucked within the rolling "hollers" of the Kentucky Blue Ridge Mountains. Upon arriving at a non-operational Equus Oils gas station, we're informed that the address that we're looking for must be somewhere along the mythical Kentucky Route Zero. This highway lies beneath the soil, within the famous caverns of the Bluegrass State. Above ground, players navigate a map along Route 65, attempting to find clues to help Conway find his final destination. As players encounter other lost souls similarly seeking a permanent resting place, they come to understand that the Zero also serves as a kind of junction between this life and the next.

Still images from Cardboard Computer (Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott), Kentucky Route Zero (video game). Act I, Scene II: Marquéz Farmhouse.

In the second act, for example, when players finally get a chance to take a tour of the subterranean highway, driving directions require activating waypoints and crystals to change the road. It becomes clear that this highway was not engineered by mortal hands, but rather by supernatural forces. A full explanation of this phenomenon is never directly given, and players are left with trying to decipher and interpret the mysteries of this phantom road.

It is in these unexplained, yet intuitive, moments that KR0 points towards a hopeful future of independent game development in that it posits a style of play that asks player not to merely solve puzzles, or to race through dialog, or to admire its realistic rendering of 3D space. Instead, this game asks players to reflect on what lies underneath the surface of appearances and gameplay. This nuanced experience invites players to develop the kind of rich relationships with characters that rarely occur in contemporary gaming.

In some moments of KR0, this invitation is next to impossible to avoid. During late stages of the first act, players have to travel through an abandoned mine on an almost unbearably slow electric trolley cart. During this sluggish ride, we learn significant backstory about the leading female character, Shannon, through interactive dialog. As Conway lays injured in the cart, Shannon divulges information about her relationship with her sister – whose ghostly presence players have encountered previously in another scene. This information is imparted to players only intermittently through long stretches of claustrophobic and quiet repose.

All too often when playing games released in the past two years – even in the most well-crafted blockbuster titles – moments of character development only occur amidst havoc and/or destructive violence. Bioshock Infinite seems one of the more fitting examples of this, as players learn the story of Booker and Elizabeth amidst brutal hand-to-hand decapitations. As a result, the potential for contemplative character-building is couched within advancing the player through some type of bullet-hell. KR0 co-creator Kemenczy suggests that this problem is not only one of content, but also of design. In a recorded interview over Skype, he commented on a central contrast between what he and Elliott have made and product from the mainstream industry, saying that in the latter "these moments … are still like a B-Side. They're just like an upgraded cinematic cut scene. [They] are not a primary concern."

In other words, within "AAA" games – or titles with enormous budgets and markets – the potential for dynamic character development manifests in the form of an apology rather than an epiphany. It is as if those brief interstitials act only as a kind of "mild interruption" in order to make a half-hearted argument that games are becoming more mature. This is only employed in order to counter-balance a more familiar, and marketable, hack-and-slash death match.

This is not to say that KR0 is unique merely because it is non-violent—many other games share this quality. What makes it unique is that Elliot and Kemenczy have created an experience where the player never quite becomes a commanding authority in shaping the way the world works. We advance with Conrad and friends far into the thicket of a metaphysical wonderland, but we never feel as though we've mastered it. This dynamic of uncertain mastery over the game becomes a central device in determining the relationship players have with their characters.

Still image from Cardboard Computer (Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott), Kentucky Route Zero (video game). Act II Scene III - Museum of Inhabited Spaces.

When players engage in dialog with characters within KR0, the player is presented with a series of responses and/or prompts to initiate further conversation, a familiar technique within contemporary games like the Mass Effect series developed by BioWare. However, players quickly discover in KR0 that these decisions actually don't create any specific or noticeable circumstance within the game, and that these choices are more about establishing tone then they are about dictating gameplay. A powerful example of this from KR0 can be found in the conversations – if that's what one can call it – a player conducts with his/her companion dog. In these exchanges, the resulting choices end up reading more like haikus than a scripted dialog logic-tree: "There are some horses out there behind the house. I guess they don't sleep in the barn. It's too spooky for a horse."

This kind of non-evaluative decision-making is a common trait of what game researcher Jesper Juul would describe as an "expressive game." In this micro-genre, which he largely identifies with sandbox-style titles, the player makes choices among a variety of options that don't dictate any specific outcome for the overall gameplay. When comparing "expressive games" to typical first-person shooters, he claims that "these games let players make decisions based on other criteria." These criteria are not based on utility and optimization, Juul argues, but instead based on a desire to make the game an expressive space.

In this way, the choosing of different dialog responses within KR0 allows the player to shape the characters in nuanced ways, and to develop an equally nuanced relationship with them. At times this relationship is uncertain, positioning the player in a space where he/she might not fully grasp the unfolding events of their interaction. This uncertainty, however, is not alienating; on the contrary, it allows players to develop an understanding of the characters and to sympathize with their desire to find a place to call home. The comfort found in these types of exchanges is a central part of what separates KR0 from other indie titles that have emerged in the past couple of years.

This is to say that playing KR0 feels like you're actually helping create a profound and insightful story – finally fulfilling a promise proposed by next-gen console developers since the introduction of the XBOX 360 in 2005. This positions KR0 at the forefront of establishing computer games as an expressive medium, one in which players are offered choices that do not relate to the completion of a mission, but drive the development of character and narrative. As such, the game offers a glimpse into possibilities for the medium that larger titles rarely explore.