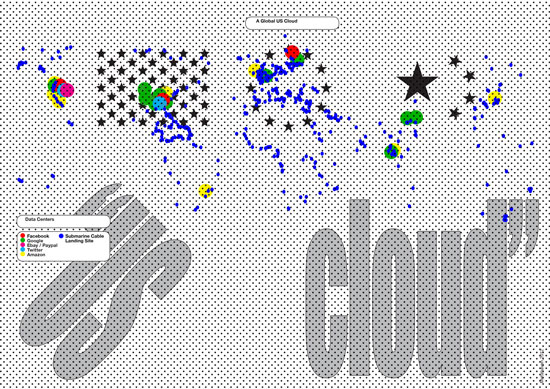

A selection of the global US social media cloud, resorting under the Patriot Act by Metahaven

E-Flux this month includes an essay by Metahaven (Part 1 of 3) on cloud computing, international law, and privacy. "Citizens across the world are subject to the same Patriot Act powers" the US has over its citizens" as data stored overseas by US companies is still subject to US surveillance. The US also excersizes "super-jurisdiction" in cases like the seizure of Megaupload, which was a Hong Kong-based company, the DOJ accused of "willful conspiracy to break US law" due it's global user base. Furthermore, "all top-level domain names" registered through VeriSign are subject to US seizure, even if operated entirely outside the country.

The essay continues, looking at examples of Apple's App store censureship of Drones+, Google+ and Facebook real name policy, and other examples of the "cloud as a political space."

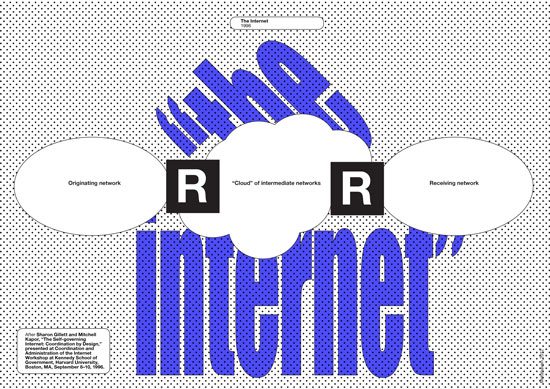

"The first mention of the notion of the “cloud” was in a 1996 diagram in an MIT research paper," redrawn by Metahaven for e-flux

Most journalism routinely criticizes (or praises) the US government for its ability to spy on “Americans.” But something essential is not mentioned here—the practical ability of the US government to spy on everybody else. The potential impact of surveillance of the US cloud is as vast as the impact of its services—which have already profoundly transformed the world. An FBI representative told CNET about the gap the agency perceives between the phone network and advanced cloud communications for which it does not presently have sufficiently intrusive technical capacity—the risk of surveillance “going dark.” The representative mentioned “national security” to demonstrate how badly it needs such cloud wiretapping, inadvertently revealing that the state secrets privilege—once a legal anomaly, now a routine—will likely be invoked to shield such extensive and increased surveillance powers from public scrutiny.

Users’ concerns about about internet surveillance increased with the proposed Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), which was introduced into the US House of Representatives in late 2011. How the government would police SOPA became a real worry, with the suspicion that the enforcement method of choice would be standardized deep packet inspections (DPI) deployed through users’ internet service providers—a process by which the “packets” of data in the network are unpacked and inspected. Through DPI, law enforcement would detect and identify illegal downloads. In 2010, before SOPA was even on the table, the Obama Administration sought to enact federal laws that would force communications providers offering encryption (including e-mail and instant messaging) to provide access by law enforcement to unencrypted data. It is, however, worth noting that encryption is still protected as “free speech” by the First Amendment of the US Constitution—further complicating, but not likely deterring, attempts to break the code. One way of doing so consists of surrounding encryption with the insinuation of illegality. The FBI in 2012 distributed flyers to internet cafe business owners requesting to be wary of “suspicious behavior” by guests, including the “use of anonymizers, portals or other means to shield IP address” and “encryption or use of software to hide encrypted data.” In small print, the FBI added that each of these “indicators” by themselves, however, constituted lawful conduct...