Taiwan Video Club

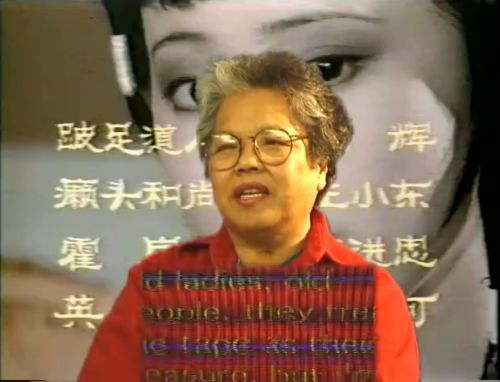

Lana Lin’s work, on display at Gasworks in London, confronts us with a number of topics: translation, identity, cultural production, and familial reflection. In doing so, her films seek to destabilize our assured hold on what we imagine we understand. In Taiwan Video Club (1999), Lin presents a Taiwanese subculture that records, trades, and holds dear, video recordings of miniseries that are shown daily on television. As we watch a participant in this practice explain her life with her collection of recordings, Lin cuts in clips and sound from the series, providing insight to a specific time and place, not to mention a specific medium which dominated it. As we come to understand this unit of Taiwanese pop-culture, Lin engages in a running commentary of sorts, provided through visual metaphors and homonyms.

Recording from TV to VHS could be seen as an apt analogy for the process of translation and cultural production that Lin seeks to examine. The final “product” in each case is a copy of the original, inevitably tinged by the process. As anyone who has spent time battling with VHS can tell you, no copy is ever pristine; there remain in the copy the battle scars of mediation: warped sound and image, deterioration of picture, the familiar markings of “CUE”, “STILL”, and “CH-3” all mark the material as part of a process and mode of production unique to video. The lens of Taiwan Video Club operates as a check on the lens of the viewer. Though we come to understand a great deal about this world of VHS-naughts, and Taiwanese daytime television, Lin maintains a field of formal intervention never lets us settle on any one interpretation of what we see.

Mysterial Power (1998-2002) projects four different short films on each of four screens accompanied by a soundtrack to be heard through headphones. As we hear a story concerning a cousin with the ability to speak to a certain god, we are also presented with footage of Lin’s family, a young woman learning (or teaching) French, an older woman praying as she moves through a street festival, and a person typing the narration into a program (EV-Dictionary for Windows 3.0). The narration is put through a translator, but the completed text differs from the voice we hear. This screen strikes me as key to the piece, acting as a crux on which the other images depend. Lin’s examination and reflection on her family’s faith, as well as the religious practices of Taiwan, becomes a new cultural object for translation, and in this case we get to watch as that process occurs.

Mysterial Power

Stranger Baby (1995) once again deals in the overarching concerns apparent in the other two works, but does so by way of what might be described as a UFO diary film. Tying her personal experience growing of mixed heritage in the west to a figurative examination of alien iconography, Lin again seeks to question her status and identity, as well as draw on the analogy felt by many to that of an alien coming to earth. Running throughout the film is a voice-over from several different people. At one point we hear what seems to be her own voice as she reflects on seeing her brother for the first time after he was born, noting he was the only other biracial person she knew, and calling the realization frightening. As the film progresses, Lin splices together images of alienation; people stare blankly into the sky, a girl attempts a communication with a man caught between a projection and reality, and throughout the film images we associate with UFOs and aliens interrupt our attempts to coalesce the onslaught. As with the other two works, a soundtrack runs tangentially to the images, sometimes featuring people describing what is on screen, other times reciting ominous dialogue.

Stranger Baby

Lin stated in a talk following the presentation of her experimental documentary Untitled Vietnam No. 18, that she sought in her work to occupy the space of the archive, a central location to the film. It would seem that in all of her work presented at Gasworks that Lin tries to occupy our space of understanding, not in the interest of obfuscation but to remove a sense of comfort or stability that one might mistakenly feel in examining others (or Others). Through collisions of voice-over, editing, interviews, and visual metaphor, her work holds a stake in the issues examined, occupying them with her personal history and aesthetic sense.