Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Digital Natives (2012)

“The internet changed the world in the 1990s, the world is about to change again,” read much of the promotional literature for the recent 3D Printshow in London. The commercial exhibitors might have benefited from a far more modest tag line, but the art work exhibited, separate from the main trade section of the show, gave much new to think about regarding the the relationship between technology and craft.

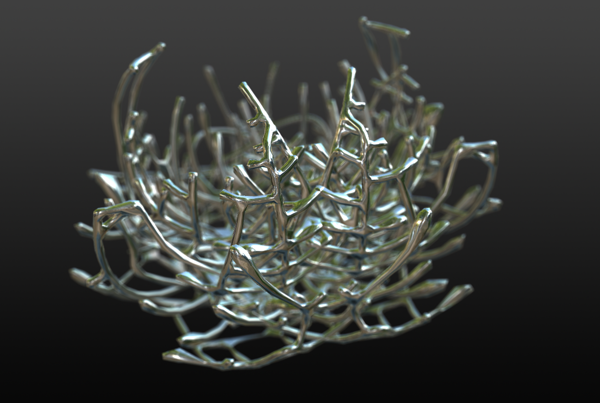

Frederik de Wilde, M1ne IIII (2012)

I was immediately intrigued by the two sculptural objects on display by Frederik de Wilde. The cobalt chrome models had been printed from data gathered from Belgian coal mines. They presented themselves as futuristic objects with a link to Europe's industrial heritage. The representations of the coal mines came to the 3D Printshow as seemingly abstract objects but, were actually formed by a much more political process. It had been a laborious process for de Wilde to get access to the data. He remarked that being granted permission to use a data source as an artist is almost an art form in itself. The Belgian government are protective over the information as the mines contain elements of interest to multinationals and other nations. De Wilde was not permitted in the work to reveal the location of the mines and had to abstract the forms so that interested parties could not gain commercial advantage. The custodians of the data had a large say in what the outcome of the piece would be. This is an intriguing collaborative process if it can be considered as such. The models of the coal mines had been stacked inside each other to create fragile vessels, that also further abstracted the context of the data. The production values of both objects were also noteworthy. I found further significance in his work as the vessels raised additional questions about how data is managed and used, a concept which is also being debated on Belgian soil by the European Courts in Brussels.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Digital Natives (2012)

Many of the exhibitors came from art backgrounds and have since developed a curiosity for technology. Matthew Plummer-Fernandez has moved in the opposite direction by taking a more creative approach to engineering. On display were objects from his series Digital Natives, produced by scanning in domestic items that were then distorted through an algorithm. His work proposes new ways in how we discuss the process of making a crafted object. Algorithms and their parameters become a tool to be mastered in the same way a lathe or a chisel would be. Plummer-Fernandez's algorithms manipulate the scans of the original objects into uncanny resemblances, defining levels of distortion and color. The results are almost alchemic and magical. We are so accustomed to machines that produce perfect objects that seeing something that for some reason doesn't seem quite correct, can only prompt us to ask questions about how something is made. To me, it is exciting to encounter objects that encourage people to ask about how algorithms are constructed. It can only lead to a desire for others to want to experiment with mechanical and digital production themselves.

The art exhibition was a space where discussions about making could take place. It did showcase the potential of 3D printing and innovative thought. However, this is in direct contrast to the rest of the show. There is a danger in using technology just to make something impressive and a lot of objects in the main trade show were produced solely to do this. I had to navigate myself through stand after stand of reproductions of the Taj Mahal, Michaelangelo's David and the Eiffel Tower. The irony being that, the originals of these were produced by combining creative and artistic insight with technology, not just by technology alone.