This post originally appeared Spitzenprodukte.

GAMIFY INSURRECTION

This week I attended Regeneration Games, a talk at FreeWord on the branding and aesthetic ideology of Olympic-driven regeneration. Alberto Duman organised the event and presented three 'artifacts' of regeneration: the ArcelorMittal Orbit Tower, a promotional PDF selling the regeneration of Newham to Chinese investors, and 'adiZones'. The author and critic Owen Hatherley was then invited to respond to 'adiZones', a small development project intended on delivering part of the “Olympic Legacy” in the form of better community sports provision

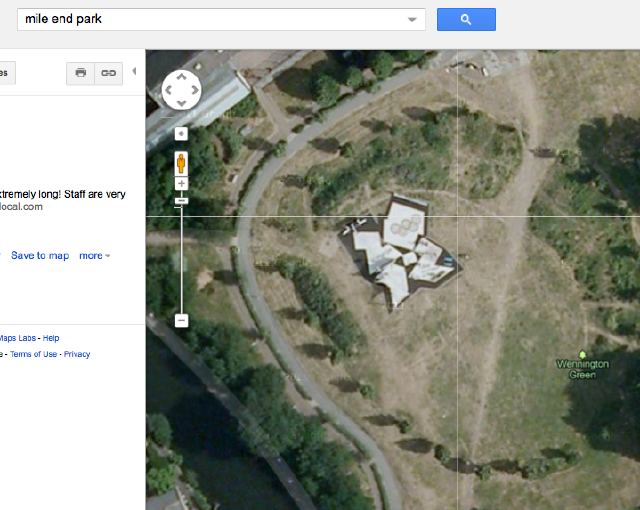

adiZones are “giant multi-sport outdoor venues” — essentially outdoor gyms — comprising “basketball, football and tennis areas, a climbing wall, an outdoor gym and an open area to encourage dance, aerobics and gymnastics” over a footprint of 625 sq m. They contain durable exercise apparatus and ‘quotations’ of team sports (for example, a short basketball court, a single football goal or a “climbing wall”). The footprint of each adiZone is in the shape of the 2012 Olympic Games logo, making the adiZone an example of “Google Earth Urbanism” — urban development conceived with one eye on the heavens and the omnipresent, panopticonic satellites that lurk there-in, guiding us to work and quietly reshaping our understanding of the urban environment. Significantly, each adiZone also has free wifi installed.

adiZone in Mile End Park, as seen on Google Maps

There are currently 5 adiZones within London, one in each of the “host boroughs”, located within municipal parks and specifically located with the intention to “renovate either disused or run down areas within the boroughs”. Nationwide there have been over 50 adiZones installed, built through a PPP (Public-Private Partnership) scheme with sportswear brand adidas (lower case theirs) contributing £1million, or 50% of the budget, with Sports England matching with funding allocated as part Sports England’s “Inspired Facilities” campaign. For such a reasonable outlay that represents a considerable “marketing legacy” for adidas, a tier 1 sponsor of the Olympics. In addition to the naming rights, they also secure exclusive advertising rights: the adiZones are emblazoned with large vinyls of their branding as well as “inspirational” decals of their brand ambassadors, Olympic athletes. Athletes are also roped in for launch events; promotional literature released by TGO, the providers of the equipment, boasts “adidas provide a Getty Image photographer at each launch and full PR support so that communities can promote their adiZone to its full potential”. The literature makes clear that adiZones provide a great opportunity to make maximum political impact for lowest possible outlay on the part of local councils. adidas also retains an important stake in the adiZone; by promising 3 years maintenance as part of the price, TGO and adidas secure access to advertising space for a guaranteed period of time. This is truly a public-private partnership in all senses of the word.

Much of the response to Owen’s presentation focused on the sad reality of the shifting of health and sports provision from the municipal authority to this slightly sleazy form of backroom deal with the private sector, and the privatisation of public space this implies. While I agree there’s plenty to be concerned about there, there was also a tacit assumption about the way working-class youths interact with brands which I found quite conservative, or at least uncritical; an idea that brands impose an ideological control over young people, a form of false consciousness which brainwashes them and turns them into “young sheeple”. I’m not at all sure that’s the case, and I thought I’d lay out some examples here which might problematise that relationship. On top of this, I also think the adiZone scheme is pregnant with unintended consequences. Both of these are tied up with issues of how young people formulate communities and group subjectivities.

THIRD PLACES

The idea of the ‘Third Place’, developed by Ray Oldenburg, revolves around the idea of spaces characterised not by work or home life but a more creative and social atmosphere. Traditionally these places may have been pubs, barber shops or coffee shops. Social network theory is complicating the idea of the the third place; many “third places” are becoming second places (i.e. workplaces) with the increase in postfordist labour practices, but also third places are being resurrected by new online communities starting to meet up IRL. Whilst in the mid 00’s much investment and hype focused on “Second Life” ideas — a separate subjectivity realised in its totality in cyberspace — theorists and online anthropologists realised increasingly that people were instead treating their meatspace/cyberspace identities in a much more fluid manner, connecting with others with whom they shared interests online before often moving those relationships into the real world.

Oldenburg lays out a number of basic precepts of the third place: they are ‘playful’ spaces, spaces where the users have no obligation to be. They aren’t (primarily) organised around consumption, conversation is the main activity in the space and they have regular users who help give the space its social tone. Under these conditions its obvious that playgrounds and municipal parks are rivalled only by bus shelters as the third place par excellence for urban working-class youth. Where I grew up our third place was the Rec (recreation ground) on the estate, where we could gather after school and at weekends to meet friends, hang out, and later drink, get off with each other, etc. The allotted sport provision was a secondary reason for attending, and frequently went unused.

Third places, then, are contested public spaces not predicated on consumption. I think it’s quite clear that, whatever attempts councils, Sports England or adidas make to socially engineer the use of the adiZones, they are potential third places with a degree of control dictated by their users. They are problematic spaces for this very reason: frequently places of bullying, but also places of youth autonomy, anti-authoritarian and anti-police. In the face of increasing state repression and social and behavioural controls, and last years anti-cop riots in London — well, in this environment, there’s something about installing free wifi in parks in London’s poorest boroughs that excites me. For London’s youth we’re seeing the creation of Temporary AdiZones (TAZ), hotspots of youth control branded with three stripes.

LO-LIFES

It is in this light, of young people reclaiming public space to use in their own way, that I think it’s worthwhile looking at similarities between this behaviour, and the way young people negotiate their relationship with branding. One thing that bothered me at the Free Word talk is the way branding was discussed as a one-way street of influence; brands manipulate and control young working-class consumers. I think this is quite a simplistic reading; in reality, brands are frequently a negotiation between consumer and corporation. Brands can be led (and smart brands allow themselves to be led, and take advantage of the promotional opportunities this can offer); displaying a degree of brand loyalty, young consumers can “inhabit” the semiotic meaning of the brand and manipulate it, make it subcultural, create a new story for the logo to tell.

One really interesting case study of this is the example of the “Lo-Lifes”. Lo-Life is a subcultural trend that emerged in the late 80’s and early 90’s in NYC, where young working-class people appropriated the clothing of Ralph Lauren Polo (PoLo-Life) and stripped it of its social meaning. Ralph Lauren as a brand has built itself around a certain conception of WASPish Americana, reflecting the values of the New England elites who attend country clubs, send their implausibly attractive children to Ivy League universities and remain a protestant stalwart of the East Coast class system. It’s important to point out that the Lo-Lifes were not appropriating that brand. Unlike, say, the young people in Paris Is Burning, there was no attempt at “Ralph Lauren Realness”. Instead they were detourning the brand, emptying it of its previous significance and filling it with reflections of their own street life.

Theft and what we might now term “anti-social behaviour” was a key attribute of Lo-Life. Lo-Lifers formed crews and gangs and the choice of various items of Ralph Lauren’s range were used to distinguish between both groups and roles and behaviours within groups. Lo-Life worked as a rejection of the class distinction that created the poverty of Brooklyn’s housing projects, and a certain pride was taken in that criminal attack on this symbol of white American dominance; for example, one crew took the moniker Polo USA, USA being an acronym of “United Shoplifters Association”. Lo-Life was more than a fashion trend; it was a way of constructing a group subjectivity from manipulating the visual language of brands to produce a consistent oppositional identity. I raise it because I think it’s a great example of the limits of brand consistency for the corporation. At some point you’ve got to let your product go into the big scary world; at that moment, no matter how carefully tuned the brand is, the consumer becomes your brand ambassador and you forfeit control, as Burberry are all too aware of.

These three vectors — the wifi-enabled adiZones, third place theory and the repurposing of brands by urban youths — raise a series of interesting possibilities. I wouldn’t like to make any predictions here, but I’m going to keep a close eye on how these weird little spaces, a collision of brand ideology, contemporary urbanist ideas, and working-class reality, are used and portrayed in the media. adidas are currently falling behind Nike in their ability to take advantage of social media, as evidenced by Nike’s very intelligent Nike+ scheme. Nike+ aims itself very much at the middle-class, urban, possibly postfordist worker. If adidas continue to market themselves as the authentic streetwear of choice for working-class youths, this draws a significant line in the sand. I’ll be interested to see how many of the speculative proposals I made last year in this trend forecast for Lucky PDF (where I examined the potential of brands to take advantage of civil disorder to make up ground on their credibility deficit, download here) will come true.