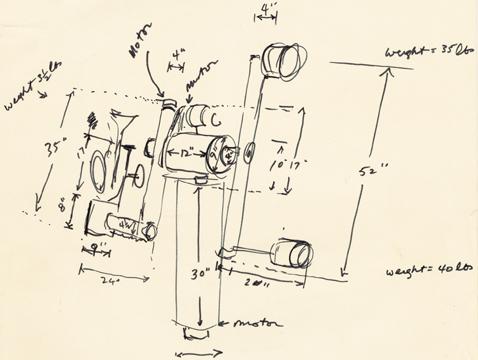

Michael Snow with the machine used for filming La Région Centrale

In 1971, Michael Snow spent five days atop a lonely mountain in North Quebec. He was making a film, or supervising a film that was being made by his robotic companion, depending on how you think about it. The film that robot made is called La Région Centrale: over the course of three hours, the machine runs through all its programmed motions, capturing every possible view of the barren mountain. Certainly, at least some of the images would have been overlooked by a human filmmaker.

Despite its lack of human warmth, Snow's film retains a mystical slant: the film is somehow purer for being supposedly unpolluted by the artist's direct physical control over the camera, and the machine bears witness to a primal landscape with nearly cosmic objectivity. The saintliness of La Région Centrale was possible not only because it played off of the machine's lack of learned perception (the machine couldn't find beauty in a landscape or respectably frame a shot), but also because the machine couldn't process the landscape as information.

Snow's sketch of the machine

Timo Arnall's short film Robot Readable World investigates the exact opposite: how robot-eyes gather information from the cityscapes, mediascapes, and people. On display in the video are the brightly colored squares, rectangles, circles, and lines that recognize cars, faces, doors and everything else that robots see. In our contemporary security-obsessed climate, robots and computer vision are tasked with growing responsibilities to survey urban and rural environments. Instead of following Matt Jones' suggestion that "instead of designing computers and robots that relate to what we can see, we meet them half-way–covering our environment with markers, codes and RFIDs, making a robot-readable world,” these machines read a world without man-made markers permitting robo-legibility.

From Robot Readable World

As Antje Ehmann describes in her notes to Harun Farocki's similar video Eye / Machine II, "The traditional man-machine distinction becomes reduced to 'eye/machine,' where cameras are implanted into the machines as eyes." Now that machines can see, what do they see and what do they make of it? Farocki's video uses footage from the Gulf War, when the covenant between visual technology and the military was finally sealed, to test the answers of these questions. From Ehmann:

It has been said that what was brought into play in the Gulf War was not new weaponry but rather a new policy on images. In this way the basis for electronic warfare was created. Today, kilo tonnage and penetration are less important than the so-called C3I cycle which has come to encircle our world. C3I refers to Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence - and means global and tactical early warning systems, area surveillance through seismic, acoustic and radar sensors, radio direction-sounding, monitoring opponents' communications as well as the use of jamming to suppress all these techniques.

Unlike the cliché of Terminator vision, in which images are translated into text for the benefit of a human audience, these computers with robot eyes have no need for a human alphabet. When the images involve text, they're there for human benefit, allowing us to interface with the machine and make sure the robot is seeing things correctly. The machines themselves don't need text: they rely on algorithmic data to understand the world they see. Whereas Snow looked to his mechanical filmmaker for almost godlike neutrality, Farocki and Arnall use their videos to begin understanding the agenda behind seeing machines. Whereas Farocki highlights the affects of robotic vision on warfare, Arnall concentrates on surveillance. Both show how, less than 50 years after La Région Centrale, the concept of a movie made by a robot has gained far more sinister implications.

Terminator identifies some motorcycles

Unlike La Région Centrale, what’s fascinating about Robot Readable World is watching robots collect data. Consumer technologies that use extensive algorithms to predict what humans want, something like Netflix or auto-tune, already have built in data to modulate its response. Kevin Slavin offers a good overview of algorithms and the role they play in society. In these contexts, algorithms are designed to create and maintain norms: they produce a monoculture where everything becomes smooth and agreeable. Watching robots gather data from cities and streets, building an archive to be understood and maintained algorithmically, some of the questions that comes to mind are: what monoculture will this data produce, and how will it be enforced? What normative behavior is being coded, and what steps will algorithms take when faced with deviant behavior?