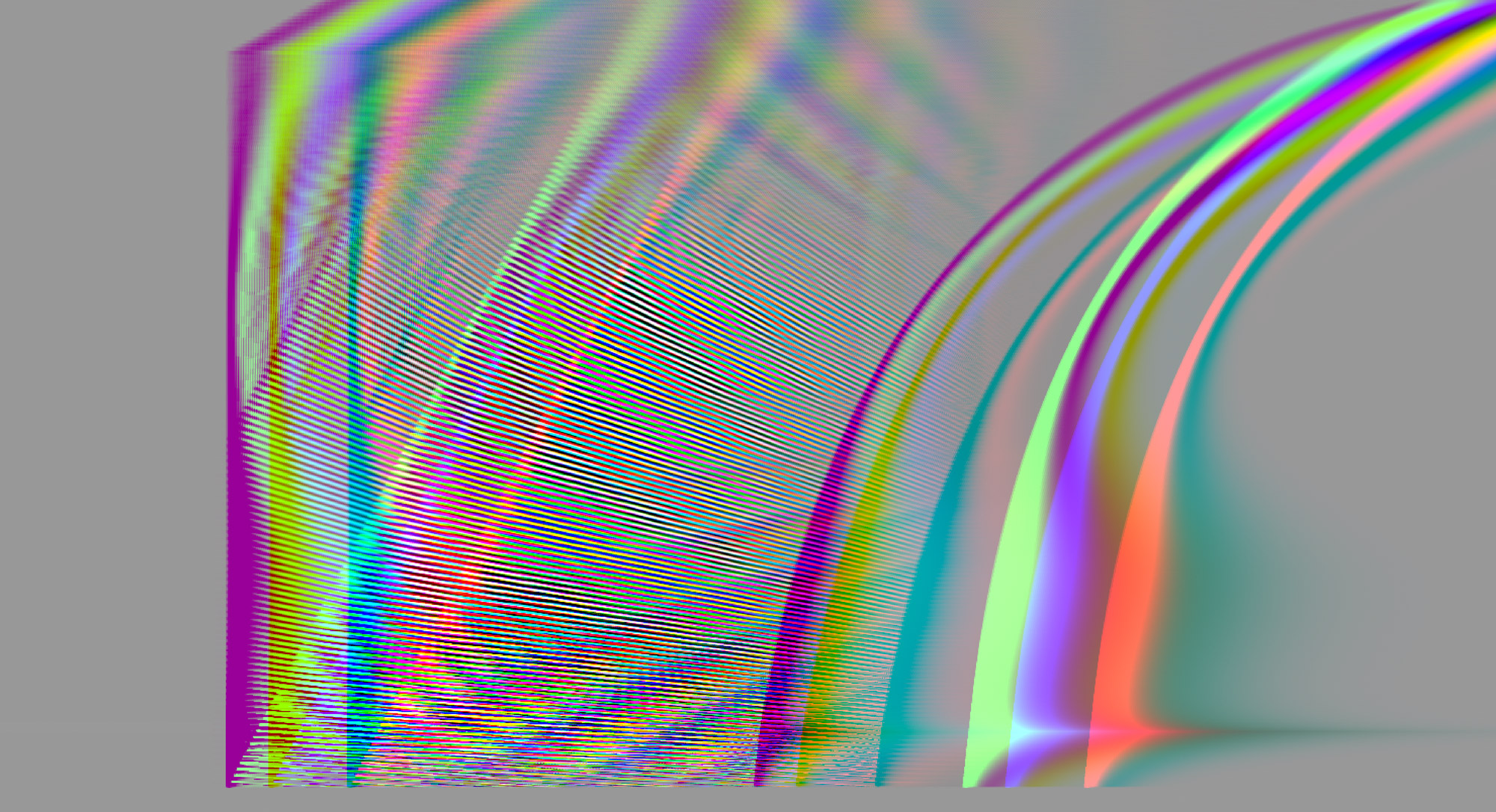

From Temkin's series Glitchometry (2011-)

You've described Entropy, an esolang you designed, as "a programming language as immersive art piece," "best experienced by a programmer working alone from home." Do you think there is a gap between new media artists and programmers--do you feel like the audience for the Entropy language is less enthusiastic about it than non-programmers who are interested in new media art? Does work like Entropy bridge this gap at all?

Esolangs, like most code art, require a knowledge of programming to use and understand; so they’ve primarily been for programmers. But the gap between programmers, non-programmers, and new media folks is closing as coding becomes a more common skill. In the Seven on Seven keynote, Douglas Rushkoff called for children to be taught programming at a young age in school, to help them resist becoming passive consumers of electronic media. I love the idea of code art in a 5th grade art class, alongside coil pot mugs.

Programming languages are logic systems, sets of rules that make up a way of thinking a programmer has to internalize to use. Esolangs take advantage of this to provide strange rule sets that play on meaning and nonsense, or otherwise construct a point of view that’s unusual. It’s in using these weird tools to solve ordinary problems that their perspectives are exposed. Brainfuck, probably the best-known esolang, is simple, clear, and functional in its definition, but requires the programmer to construct long rants of gibberish to use. It reminds me of work like Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes (1974), where exploring a rigid, contained system takes us on a ludicrous journey. Because brainfuck refuses to concede to the human thought process, it dramatizes its collision with computer logic.

With my language Entropy, I address my own experience of programming for a living. I find programming to reinforce compulsive thinking: the obsessing over nagging details and edge cases, which can’t help but bleed over into other parts of one’s life, where such patterns of thought can become neurotic and unhelpful. Entropy is a release, an unclenching. In the language, all data decays over time, so there’s no way to get things “right.” At best, a programmer has a short window to get a gesture across before the program becomes muddled and falls apart.

In writing Entropy, I had this gap between programmers and other creators/audiences in mind, and so I decided to illustrate the language by rewriting the classic chatbot Eliza in Entropy. The result was Drunk Eliza. As you converse with the program, her words become increasingly slurred until she collapses into incomprehensibility.

But putting a program online that impersonates a drunken female brought out a different set of issues. About half the conversations people have are hitting on her or coercing her into sexual acts. One user commented “I can’t believe I’m spending my Saturday night hitting on a drunk chatbot from the 1980s.” Others relate to her drunkenness and type long streams of nonsense. So, in the end, the programmers using the language directly had a different experience those who only know the language through Drunk Eliza.

At least some of your work -- like "Meanwhile, in New York" (2011-), "Metro Postcards" (2009-), and "Mutator 1" (2010-2011)--seems very concerned with the representation of transforming urban spaces. The "Metro Postcards" depicts mostly chain locations within urban spaces through an ironic postcard form, while "Meanwhile, in New York" takes a time-based "shifting landscape deep in the boroughs" as its subject. Can you talk a little bit about those ongoing projects and the role you see technology playing in the transformation and depiction of urban spaces?

New York City and the web mythologize their pasts in similar ways. They’re both constantly in states of commercially driven re-invention that make them more convenient but are perceived as threatening to some core character. There’s a feeling you always arrive too late, but they have highly mutable histories.

The Metro Postcards commemorate storefronts by displacing nostalgia onto what has replaced them. However, over time, even generic consumerism becomes specific to the places they live: a Budapest KFC is very different from one in Queens. But at the same time, there’s no reason we can’t truly come to feel non-ironic nostalgia for these chain stores decades from now (as I do for Sears in another project).

Mutator 1 and Meanwhile, in New York… are both street photo projects, each centering on a form of urban isolation. Meanwhile, in New York is tied to the early web in its mode of presentation. The source images were shot on day-long hikes through Eastern Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx: the majority of New York City, but the parts that are least often represented. It’s constantly shifting, covering a huge swath of the city, yet never seeming to really change in character. Mutator 1 uses older technology (specifically a mid-Century electrical generator) to invoke a cold war sci-fi dystopia, a setting for patterns of facial expressions and (lack of) public interaction by an older generation in a central European city.

In "Notes on Glitch," a collaborative piece with Hugh Manon, you say that "At its core, glitch holds a reverence for the objet trouvé: the computer error caught in the wild." Can you describe your attitude towards the "hunt" for wild glitches? Do you have a specific process in your hunt for glitches?

I’m delighted by chance encounters with glitches out in the world -- on an airport kiosk, a Times Square billboard, a classroom projector. However, I rarely record them -- for me, the joy is in the immediate experience, but heightened by having spent a lot of time looking at glitch art.

My glitch work, like many of my other projects, is rooted in miscommunication and failure of connection. It stems from a wrestling with the computer. I try to make things look a certain way and the machine works against me, until we reach a compromise far from where I had intended to go. My Glitchometry project is an example of this: each image begins as a square or circle, and through repeated manipulation in a sound editor, ends up in a completely new place. I have a vague idea of what each sound effect applied in a specific way might give me, but where I end up is not possible to control.

You've imagined a series of work from your recent show "dfghfhg" as products sold at Sears. I'm curious about the thinking behind your action here. Do you think there's something about pattern and abstraction that somehow lends itself more readily to fashion and consumer goods? Yves Saint Laurent's Mondrian dress is a good example, but one that remains within the realm of haute couture. What's the relationship between that and your B Smart Junior's One-Shoulder Dress -- presented as available through Sears for $89.99?

For many, viewing art is a passive experience: one stands in front of a piece and waits for some kind of experience to materialize. But shopping is never passive, we feel entitled to engage with something or breeze past it. Art presented in this commercial form can escape a stuffy confinement and preciousness.

I picked Sears initially because there’s already something jarring about its web presence. As a kid, Sears was a place that could always be counted on to disappoint. You knew they had toys, but somehow could never find them; it was a place to be dragged around by adults who bought objects that seemed to stink of grease before they were even opened. In sharp contrast is the current-day, online shopping experience, which is orderly and antiseptic—everything is disappointingly easy to find. It’s reminiscent of how Don DeLillo described the pseudo-religious experience of the American supermarket in White Noise: a shiny, clean Purgatory where death is impossible and “everything is concealed in symbolism.” In a sense, we’ve brought the supermarket home in the form of the commercial website; it provides a structure around which we can cleanly arrange our thoughts. The banality of the web is at odds with the banality of the department store, which is chaotic and earnestly mediocre, and these two things come into a wonderful synthesis on sears.com.

All the best artists end up at Sears eventually: Monet becomes a color palette for pillows, Mondrian a template for bedspreads. I’d like to help others make this transition. So I’m expanding the Sears project into a larger, collaborative art mini-mall of sorts. I want to flatten the strip mall and online shopping experiences into one, and to curate contemporary art as lamps and sofas with no material form.

Age: 178 (in negadecimal)

Location: Queens, NY

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

One day I opened ResEdit on a Mac Plus, the family computer. It was forbidden and dangerous: the place icons could be messed with, full of numbers with no context, relied on by the machine in ways that I couldn't understand. An inner sanctum. This was reinforced by the icon of a jack-in-the-box, its head jutting out at a libidinous angle. I went in and began typing random numbers, disturbed anonymous strings of data, unsure of what would happen.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

I mistrust tools, most have a cliche aesthetic or way of working attached to them.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I recently completed my MFA in photography at the International Center of Photography / Bard College. As an undergrad, I studied film and philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

Is photography traditional? Not sure where the line is. I like bookmaking. I’m working on a larger project that involves painting; so far it seems messy and difficult.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I play guitar and sing for my girlfriend.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I write software -- it feeds the neuroses I rely on for my artwork.

Who are your key artistic influences?

Sol LeWitt, Fluxus and John Cage, Anni Albers, Walker Evans, Lewis Baltz, Lynda Barry, Cory Arcangel, JODI, Martin Parr, Hans Aarsman, Sophie Calle, Andre Cadere, many more

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

Yes, many, either directly or by remixing each other’s work. I release most of my work under a Creative Commons license or GNU GPL.

Do you actively study art history?

Yes, and I surround myself with art books for inspiration. For a graduation gift, I received 100 Great Masterpieces of the Mexican National Museum of Anthropology. It has nothing to do with anything I’m working on, but both the pieces themselves and their hypersaturated 60s photographs are inspiring for me.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

I’m usually reading some kind of art history or theory. Right now, I'm reading Caleb Kelly’s Cracked Media. I’ve been told I should read Flusser, maybe he’s next.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

There are lots of open questions I hope don’t resolve too quickly, it’s exciting to work in this form right now.