Singluar Oscillations: Correspondences (email), 2008

First, could you talk about your two degrees in Aeronautics and Astronautics? Specifically describing the moments when you decided to reroute the instrumentalities of your field, and pursue them instead in a highly singular, individualistic exploratory way?

I started MIT thinking I wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist due to the philosophical implications of that field. I quickly realized though, that I needed more tactile engagement in my work in order to be satisfied. Aeronautics and Astronautics was a way for me to combine my interests in space and material. It mixed scientific concepts with material application, but wasn’t able to satisfy my desire to contemplate and build meaning. Only in my architecture and visual arts studies did I find a space to combine concept/theory, material, and meaning into a “tactile philosophy”. In these disciplines there was less discussion about rules and solutions, and more discussion about one’s interpretation of context, intent, and the implications of one’s process. This opened up the possibility of designing experience and meaning over objects and functionality.

Throughout my undergraduate studies I thought I would go on to get a Masters in Architecture and be an architect, but this changed when I was part of a team that conceived, designed, and built a group of micro satellites. At the end of the course we tested them aboard NASA’s parabolic-flight aircraft, the “Vomit Comet”, which produces 25-second periods of weightlessness and double-gravity. Instead of going to grad school in Architecture I got a Masters of Science in Aeronautics and Astronautics where my research was on advanced spacesuit design, a perfect combination of my interests in space, architecture, and bodily experience.

If there were any major turning points, they were spread out over my time at MIT. The first major influences were art professors like Julia Scher and Krzysztof Wodiczko. Julia exposed me to the idea that art functions in society like a mirror, reflecting the artist’s perspective back to the rest. This was the first time I saw the deep value of a rigorous art practice. Krzysztof, an industrial designer turned artist, took this further by exposing me to the vast implications of design and technical development. After studying with him I could no longer see science and technology as “neutral”.

Many of my thoughts and feelings about science, technology, and society were crystalized in the year I took off between finishing my bachelors and starting my masters. In this year I traveled in Europe, worked as a physical laborer on a construction site, interned at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, and spent the summer as a camp counselor at the camp I attended as a child, whitewater kayaking and camping throughout the southeast. In driving from NASA to summer camp I listened to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance as a book on tape, which put many words to my experience and questions. Immediately after finishing the tapes I bought the book so that I could underline and take notes, which I did at least twice.

All this is to say that arriving at MIT for my Masters, my head was filled with questions, doubts, and possibilities. Working in the lab I felt I was asked to be only the highly rational, positivist side of myself. In the end this felt too fractured and by the end of my masters I had decided to lift the limitations of science from my practice and pursue my interests in a self-directed way. Art felt like exactly the right context to do this.

Today, much of art abandons the dictates of medium specificity and attempts to intervene into life, which means existing within other disciplines and merging them. It’s clear with works like, Singular Oscillations, Nested Voids, and One Roll of Weightlessness (among others) that you do just this. What is your ‘professional’ relationship to the scientific community? Are you in anyway acknowledged?

I don’t consider myself part of the scientific community any more. I certainly interact with that community for projects, but as your first question hints at, my priorities have shifted away from that arena. I am fortunately conversant in technical/scientific conversations, but it would be wrong of me to currently claim I’m an engineer. I respect the skill of engineers too much for that.

My masters’ research on spacesuit design was continued by other students after I left MIT, and is most likely referenced in current spacesuit design literature, but other than that I leave the publication of the technical aspects of my work in the hands of my technical collaborators. I certainly hope that our collaborations have bearing on the scientific or technical communities, but they are in a stronger position to determine if or how that is the case. I do not gauge the success or failure of my work in those terms.

Western society (at least a large majority of it) since the 19th century has largely been influenced by a positivist philosophy of sorts. Your work is literally evident of this philosophical system, specifically in your continual investigation of sensory experience. But, rather than undertake the pragmatics of scientific experiment you re-negotiate its utility through play. You briefly presented similar thoughts at the ISDC conference in 2006 and I'm wondering if you could you further extrapolate on these notions of uselessness and pointlessness? How can one navigate the spectrum of use, progress and play?

It’s interesting you connect positivism with sensory experience as I usually think of it in terms of measurement and falsification, which to me feels disconnected from experience. Of course there are many forms of positivism, but my dedication is to experience and unanswerable questions. As I stated before, I am not so interested in producing unfalsifiable statements as I am in probing possibility and belief, raising questions and rich complexity in the process. This feels like the way to open up meaningful exchange and learning. Answers often feel like the ending of a conversation (as we have all experienced with the ubiquitous use of Google searches on mobile platforms while trying to have an exchange with another person).

Perhaps it is due to my background in engineering, but I am weary of utilitarian function and the ideal of “progress”. In the state of play these (and most other) terms have no meaning because there is no self-awareness to bring one to a meta level. This doesn’t mean that play can’t produce something “functional” or “progressive”, but these labels can only be applied after the fact. As summarized by Joseph Beuys, “man [is] a man only in play, and only in play is he free, and, as such, a real man! Therefore art, understood in the sense of play: this is the most radical expression of human freedom."

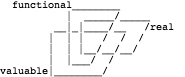

In my artist’s statement I consider the relationship between the terms “functional”, “valuable”, and “real”. It seems to me that the globalized world is increasingly pushing these terms to be synonymous. Only those things which are functional are valued (and valuable) and therefore real. The rest is considered frivolous fantasy, without any real bearing on the world. I want to disturb the logic that binds the terms “functional”, “valuable”, and “real”, by creating work that inhabits regions where these terms are not all equated. Is it possible to create something that is either “functional”, “valuable”, or “real” but not the others? How about something that is two of these but not the third? What would these possibilities look like and how would they inhabit the world? Perhaps they couldn’t inhabit this world, but what sort of world would it make if they could?

Game developer and academic, Ian Bogost, at the end of his most recent book Alien Phenomenology, proposes that thinkers should not only just ruminate and write, but actually do and make. I feel this is an approach you've adopted and actively developed. You even describe your work as ‘ontological research’. What are your thoughts on the field of academia moving in this kind of hybridized direction? What does it mean for you?

I must admit that I am a bit weary of traditional academia because so much energy there seems to be spent on proving one’s correctness and engaging in debate rather than just doing what feels right. It seems to stifle individual expression, which is the most generative element available to us. I turned down the chance to get a PhD because I realized that I do not want to be putting the majority of my energy into theorizing or building rock solid arguments. I want to use my time to realize my visions in the ways that make most sense to me at the time and in that way demonstrate my own model of operating in the world. I try to approach thought systems and the world at large as an open playground. I don’t believe any single tool can access all of reality or experience so why limit myself? For me, the messy, self-contradicting, hybrid methodologies that I engage in seem much closer to reality than any rational argument ever could.

While I have chosen a hybridized direction for myself and value similar attempts of others, I certainly feel the pure investigations of academia have their place and are extremely valuable. My fear, however is that the academic, pseudoscientific value system is laying claim to more and more of our society, asking everything to be known or hypothesized before any action or risk can be taken. I find this extremely dangerous and scary and hope to push back on this trend by pursuing “things that talk” as defined by Lorraine Daston:

“It is precisely the tension between their chimerical composition and their unified gestalt that distinguishes the talkative thing from the speechless sort. Talkative things instantiate novel, previously unthinkable combinations. Their thingness lends vivacity and reality to new constellations of experience that break the old molds. … As in the case of constellations of stars, the trick is to connect the dots into a plausible whole, a thing. Once circumscribed and concretized, the new thing becomes a magnet for intense interest, a paradox incarnate. It is richly evocative; it is eloquent. … Like seeds around which an elaborate crystal can suddenly congeal, things in a supersaturated cultural solution can crystallize ways of thinking, feeling, and acting. These thickenings of significance are one way that things can talk be made to talk.”

Expensive, precise technological equipment and process allows you to intimately and intricately examine the body in space, emptiness and weightlessness. Similarly, Speed of Lights, a human (you) suspends himself of all rationality in a struggle to outrun motion sensitive lighting (or the mathematical precision of the machine). What can you say about the role of machines in your practice? About cybernetic theory even?

I sometimes see my education as a curse to my art practice. Having studied at MIT I was exposed to many tools, techniques, and processes which fuel my visions. If we could put a man on the moon in the 60’s (yes, I believe we landed a total of 12 people on the surface and returned them safely to earth), then you can’t tell me that my art proposals aren’t possible (I happen to believe Apollo was an artwork in itself, but that’s another story). Because of my education I know things are possible, but rarely have the funds to do them. Sometimes I think ignorance would be more blissful.

In terms of the role of machines in my practice, I often try to break them. I don’t mean I try to physically destroy them, but I try to turn them in on themselves by subverting the intentions for which they were developed. For example, with the Ellipsoidal Introspective Optic (EIO) I was interested in making a high-precision mirror for my eyes only. The tools needed to realize this were developed in the name of science and objective measure, but I wanted to use them to produce a singular, subjective, undocumentable experience. Not surprisingly this raised tensions with the primary sponsor, the Dutch Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Science builds a community and reaches the masses through objective quantification. In the process the individual, unique, and obscure often get stripped in favor of the common, general, and repeatable. Art, on the other hand, builds a community and touches society through a nearly opposite pathway: through the subjective. Instead of appealing to the notion of “higher truth” as science does, art appeals to deeply human experience. By revealing internal truths/desires art touches the internal truths/desires of others. It is in this context that I think of cybernetics a la Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics and Society, which considers "communication" as the fundamental feedback loop within society. I belive in his perspective, though I prefer a broader notion like "communion" over "communication".

Age: 34

Location: Brooklyn, NY

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

I guess this started while I was an undergraduate at MIT. It was there that I started thinking about art as a rigorous, conceptual practice, with an important, powerful role in society. Krzysztof Wodiczko, an art professor of mine, was a major influence, getting me to think about the implications, ethics, and meaning of technology/design. By the time I got to grad school in 2001 I was deeply questioning the technical community and my part in it, seeing space exploration as primarily an art endeavor, though it was cloaked in the language of politics and science/technology. In grad school I was lucky enough to have a very open minded advisor who allowed me to explore these thoughts/feelings in my thesis, which turned out to be two parts conceptual and one part technical. In many ways, my thesis work on spacesuit design was my first fully invested exploration into technically based artwork.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

Most of the technical tools I use in my artwork I am employing for the first time. I do not have prior experience with them. Sometimes I encounter a tool because it is the only tool that can realize my vision (the vision drives the choice of tool), but sometimes I find the tool itself so inspiring that I develop a work around it. The single-point diamond raster-fly cutter used to create EIO is an example of the first case. I had no idea such a tool existed and felt very fortunate to work with the technicians to use it. My work with the solar powered furnace in southern France for Blind Spots #6: Sun Spots is an example of the second case. Its existence was too much to ignore and I felt there was potent meaning embedded in the tool itself. Actually this is a large part of how I relate to tools/technology. I see them as the physical manifestation of questions (a.k.a. “desires”) and I read them to uncover those questions. As Cedric Price said, “Technology is the answer, but what is the question?” Some questions are so powerful that the lineage of a tool stretches over centuries, like the telescope. We will never stop making telescopes because the desire to answer those questions will never be satiated.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I did my undergrad and masters at MIT. My BS & MS came from the department of aeronautics and astronautics, but during undergrad I minored in architecture and visual art. In grad school half my course load was in visual arts, so by the end of my 6 years of study there I think I roughly had enough credits for a degree in visual arts. After working for two years on my own as an artist I moved to Amsterdam to attend the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, where I was a resident for three years (two years as a regular resident and one year as the “Resident Researcher in Art/Science”). The Rijksakademie is not a degree-granting institution but was a crucial part of my education and immersion in art.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

The most “traditional” media I use is pencil and paper. I wish I drew more, actually. The ways I’ve used in my practice can be seen with projects such as Blind Spots and Singular Oscillations: Body Coordinates.

I find drawing to be a beautiful, direct, intimate action and result, which contrasts nicely with technology. Although machines can write and even simulate drawing, I feel the true act of drawing is something only a human can do because it is so embedded in the experience of observation. There is a beautiful example of this from the Space Race in which Aleksei Leonov (the first person to perform a “space-walk”), who wasn’t allowed to touch anything in the space capsule, brought with him a color pencil set adapted for weightlessness. Because he had no manual tasks to do, he was able to take the time to sketch the horizon from space, something only a human could do. This story is a beautiful embodiment of Oskar Schlemmer’s statement, "a further emblem of our time is mechanization, the inexorable process which now lays claim to every sphere of life and art. Everything which can be mechanized is mechanized. The result: our recognition of that which cannot be mechanized."

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

Not so much in the sense that you are hinting at, though I played many instruments growing up and love to dance. Improvising live on stage (in my high-school jazz band, for example) is I feeling I miss and haven’t found elsewhere.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I spend most of my time working in the studio and investing in an art practice that can support my living. On the side I have had freelance consulting gigs with an ad agency. In that context I bring my technical background and conceptual thinking to bear on their work, generating new ideas of how to realize a given strategy. Basically I am hired as a brainstormer to help them “ideate” (I was even told I was being hired to help with the “ideation of ideas”. I’m not sure what that means, but they are excited by my contributions so I keep showing up to offer my perspectives).

Due to the atmosphere of the ad agency, this work has opened me up to the creative potential in public and commercial space. Creating a meaningful experience is still my priority, but I am now considering other models for support in addition to the studio art model. For example I am now making the Yearlight Calendar, a made-to-order, site-specific calendar which maps the duration of daylight, twilight, and moonlight throughout the year for a given location, specified by the customer. It is a product that comes out of my conceptual interest in the slippage between personal experience and standard measures. I am selling these online at: www.yearlightcalendar.com

Who are your key artistic influences?

(This is starting to feel like filling out an online dating profile, which I may or may not be copying and pasting from...)

Not necessarily in order:

James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Joseph Beuys (mainly his writings), Dan Graham, Krzysztof Wodiczko, William Wegman’s early videos, Mitch Hedberg, Steven Wright, Nancy Holt, Urs Fischer, John Baldessari, Harun Farocki, Robert Barry, Larry Walters, Tino Sehgal, Jonathan Safran Foer, Miranda July...

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

An artist friend, Dominick Talvacchio, and I collaborated on the project Sunrise OR Sunset and its many manifestations. This project is interested in the (dis)symmetry between sunrises and sunsets: the beginning of day and the end of night, the beginning of night and the end of day. The project is based on a Google image search for terms marked by either the term “sunrise” or the term “sunset” and displays the image results without identification. (The all-capital Boolean operator “OR” is used to locate images marked by either term.)

Website: www.sunriseorsunset.net

About the project and other manifestations: http://bradleypitts.net/projects/sunriseorsunset/2/

Do you actively study art history?

Unfortunately I can’t say that I do. I dive into it when appropriate for the projects I am working on, but rarely do I seek it out for it’s own sake.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

My reading interests are wide and varied, sometimes dipping into philosophy and theory, and sometimes into fiction. I find inspiration everywhere. A few authors that have influenced my thinking (again, not necessarily in any order):

Jacques Ranciere, Joseph Beuys, Merleau-Ponty, David Lewis-Williams, Robert Irwin, Lewis Mumford, Miranda July, Jonathan Safran Foer, Ayn Rand, Norbert Wiener, Victor Papanek, Robert Pirsig, Scott McCloud, Lorraine Daston…

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

Yes, especially terms like “new media art”. I understand the desire for such a term, but terms like these usually emphasize the newness of techniques and materials over the artwork itself (the material over the meaning). I can get with “the medium is the message” as much as the next guy, but that seems even more reason to focus on the arts meaning, not the fact that it’s material/techniques are “new”. It seems that an overarching term focusing on the media/techniques of art is only valuable or appropriate if artists are using the media to comment on the media itself. When this is the case there is usually a community and conversation driving the use of those techniques. If not, the term feels like it’s putting “the cart before the horse”.

I am also concerned about issues of documentation. I tend to question the need/want for documentation in the same way I question the need/want for objective measurement and solutions or final answers. I fully stand behind artists such as (young) Robert Irwin and Tino Sehgal who prevent documentation of their work and I find the inescapable “failures” of this stance very interesting. Our systems (society, politics, industry, academia, etc.) are built on documentation and do not consider something real or true without it. Try fighting a tax audit without paper trails and other “proof” and you’ll quickly run up against this (so much for “innocent before proven guilty”). Even an artist like Tino Sehgal who tries his damnedest not produce anything material is still caught in the web of material production via ticket sales, invoices, wall paint, etc. I would love to collect all the materials he is forced to employ, not to criticize him or his work, but to display the inescapable dominance of the materialist belief system we are embedded in.

I am very interested in producing the undocumentable. I’m not really sure what that means or looks like, but that’s why the possibility holds my interest. Again, I’m not sure if the undocumentable can truly occupy a place in our culture, but I think I’d like to live in a society that could fully value the undocumentable.