At a time when so many Americans are disgusted with the personhood of corporations, it's surprising that more persons don't move to secure their expanded rights. Dan Graham notes, “Jasper Johns was the first American artist to fully understand that the newly subjectivized advertising icon and the gestures of Abstract Expressionist painting—which struggled against the cultural domination of this new form—were virtually identical.”1 The place of the (white male) individual and his potential for transcendence had already merged with corporate strategy. Warhol began operations at his Factory in 1962, and by 1966 Foucault proclaimed that man “would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.” In 1978, the band Devo told The SoHo Weekly News that they’d decided to “mimic those who get the greatest rewards out of the business and become a corporation."

According to Bernadette Corporation, “Mock incorporation is quick and easy … no registration fees, simply choose a name (i.e. Booty Corporation, Bourgeois Corporation, Buns Corporation) and spend a lot of time together. Ideas will come later.” Bernadette Corporation was founded in 1994 as "the perfect alibi for not having to fix an identity."2 Similarly, the Bruce High Quality Foundation employs a post-individual aesthetic while using the language of a endowed institution as opposed to a corporation. Yet the post-individual kernel is clearer in the Foundation’s mission, which presents itself as the arbiter of the estate and legacy of “the late social sculptor” Bruce High Quality. The Foundation is founded on the negation of an already fictional identity. The Icelandic Love Corporation, based in Reykjavik, adopts the title of a corporation without jettisoning their identities.

Corporate art practice challenges stale narratives of contemporary art, which resuscitate themes and tropes of 20th century conceptualism. By claiming the featureless corporation as the active artmaker, BC and other similar façades maneuver around cliché and retreat from the individual artist-archetype: a character to be media-narrativized into a pop-psychological explanation of their noble craftsmanship or pathology of resistance.

Bernadette Corporation's The Complete Poem installation at Greene Naftali (2009)

Corporations, much like contemporary art, have a unique relationship with the iterable. In an essay discussing the irony of the corporate sponsors of the San Diego Zoo, critic and writer Chris Kraus explains, “Like contemporary art, corporate linguistics seeks to eliminate the dreary mechanics of cause and effect. Shit happens. People demand.”3 Corporate language rests on clichés that are instantly understood. Phil Spector reportedly wondered, “Is it dumb enough?” while listening to “Da Doo Ron Ron.” The question that defined popular music has as much bearing on contemporary art: unencumbered by the boring (Kraus’ “dreary mechanics”), only that which is instantly understood remains. That which is dumb enough.

The artist Ed Fornieles, whose work includes the trend-forecasting agency Recreational Data and the management training company Coaxiom, indicated to me that part of what he likes about working with corporate aesthetics is the power of boring corporate cliché both in language and imagery. “Corporations have their own logic,” Fornieles told me. “It doesn’t always have to be about me.” In a sense, engaging with corporate style makes transparent a generic corporate aesthetic—visible in promotional materials, architecture, offices, commercials— which is both recognizable and unfixed. What’s appealing about something so blandly real is its ability to blend into the fabric of reality without the risk of a unique stake or identity.

A logo for The Dreamy Awards by Ed Fornieles

In their 1996 video The B.C. Corporate Story, Bernadette Corporation uses of the structure and style of internal corporate mission videos while spouts generic corporate lingo about hard work, analysis, and markets over images of fashion photography before ultimately showcasing catwalks from BC produced fashion shows. “Makin’ clothes, man…there’s quite a lot to it,” says the narrator in a Southern business monotone. BC’s emphasis on fashion, corporate identity-forming art, emphases the double-bind selfhood as predetermined individual preference. BC member Antek Walczak remarked to Chris Kraus, “What are people’s problems with fashion? There’s a blind spot—people think fashion is uniquely superficial, as if everything else is not.”4

The video ends with the opening scene from Blade Runner. The invocation of Blade Runner, which depicts a world in which the Tyrell Corporation manufactures robots virtually indistinguishable from humans (known as replicants), takes the place of a traditional video-ending corporate mission statement. The tension of Blade Runner comes from Harrison Ford’s own inability to know whether or not he is a replicant. The difference is imperceptible, what’s important is that the Tyrell Corporation is a company that can create individuals, which is less a science-fiction speculation than a capitalist reality. Like Ford chasing the replicants, the battle-line between superficiality and authenticity has become variable to a degree that makes it negligible. Instead of fighting for semantics, it’s preferable to become the Tyrell Corp. If having an identity is merely an excuse to be absorbed by consumer culture, the only sensible way to escape that assimilation is to align yourself with the corporate agencies of capital.

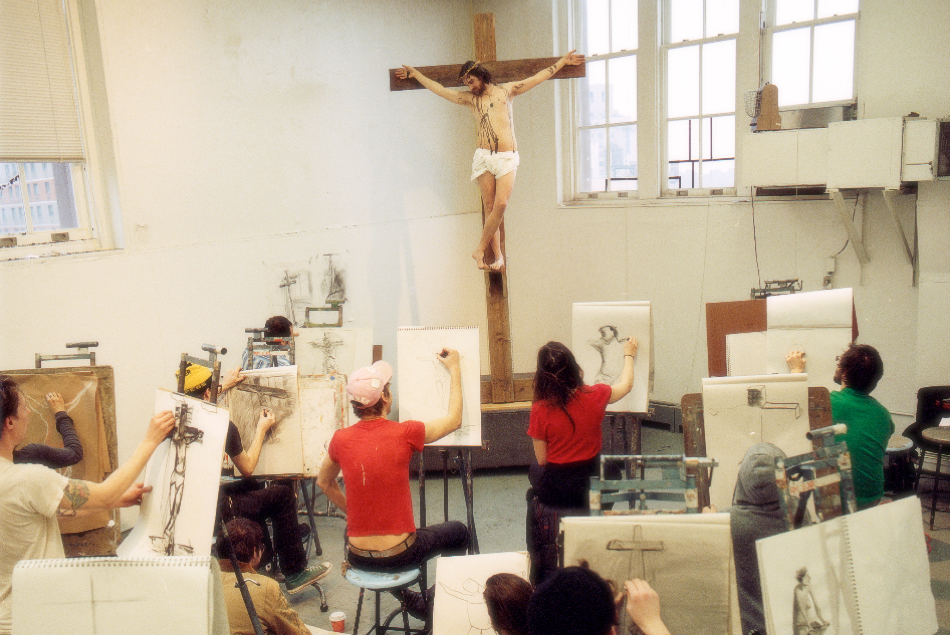

From Bruce High Quality Foundation's 2008 Retrospective

Bernadette Corporation’s 2003 video Get Rid of Yourself is an anti-documentary featuring footage of the 2001 G-8 riots in Genoa. On their website, Bernadette Corporation describes the video as “an encounter with emerging, non-instituted or identity-less forms of protest that refuse the representational politics of the official Left.” BC’s goal here is to utilize the representational form of video without closing, halting, and commodifying the event as “something recognizable.”

If corporations have potential in an aesthetic context, can art have a totally corporate form? In her essay “Indelible Video,” Chris Kraus compares the strategies of American Apparel to the strategies of contemporary art: “The company’s merchandising aesthetic includes the display of amateur-produced art that reprises—like much MFA art—reprises various landmarks in conceptual art of the past decades…Recruiting talented young women as both content-advisors and sex partners, [Dov] Charney creates a paradigm for how life can be lived a different way.”

Kraus goes on, “It could be argued that entrepreneurial ventures like American Apparel fill the void left by avant-garde process-art projects of the last century, which are no longer practical for artists who must maintain their careers … American Apparel resonates against the economic and psychogeographic state of the culture like a gigantic work of conceptual art.”5 What makes this argument so compelling is that a corporation’s status as a for-profit enterprise does nothing to exclude it from the realm of high art.

As the Bruce High Quality Foundation mentions on its website, “Only Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol compared in their conflation of art with the systems of modern media.” Yet both of those artists couldn’t escape the grasp of identity: endlessly psychologized, their strategies for dismissal of the self created an even greater aura of personhood around the place where the person should have been destroyed. Warhol tried to get rid of himself using the model of a Hollywood studio. Auteurism injected that model with individuality and personality. He should have looked to IBM.

1. Dan Graham. “The End of Liberalism.” In Rock/Music Writings. New York: Primary Information, 2012. 50-60. 55.

2. Quoted in Chris Kraus' "The Complete Poem/Bernadette Corporation." In Where Art Belongs. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011. 44-56.

3. Chris Kraus." "Panda Porn." In Video Green. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2004. 159-164. 163.

4. Quoted in Chris Kraus' "The Complete Poem/Bernadette Corporation." In Where Art Belongs. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011. 44-56.

5. Chris Kraus. "Indelible Video." In Where Art Belongs. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011. 119-139.