Interview with Stan VanDerBeek from John Musilli's 1972 documentary The Computer Generation

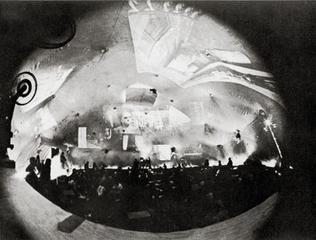

Jonas Meekas crowned Stan VanDerBeek the "laughing man of the bomb age," refering to his starry-eyed embrace Cold War technology and its transformative aesthetic and spiritual potential. Of VanDerBeek’s numerous large scale proposals, his Movie-Drome was the most fully realized. VanDerBeek began creating films for the Drome in 1957. Built next to his home in Stony Point, NY, the Movie-Drome operated between 1963 and 1966. During that time, viewers would lie on the floor with their heads against the wall and watch and watch projections throughout the dome’s interior. It's visible at the New Museum as part of the exhibition "Ghosts in the Machine" next week until September 30.

Interior view of the Movie-Drome in action

The full potential of the Movie-Drome, as proposed in his Culture: Intercom manifesto, was not fully realized. In that tract, VanDerBeek proposed:

That immediate research begin on the possibility of a picture-language based on motion pictures.

That we combine audio-visual devices into an educational tool: an experience machine or "culture-intercom."

That audio-visual research centers be established on an inter-national scale to explore the existing audio-visual devices and procedures, develop new image-making devices, and store and transfer image materials, motion pictures, television, computers, video-tape, etc.

That artists be trained on an international basis in the use of these image tools.

The Movie-Drome was to be the exhibition space for these experiments: a network of Movie-Dromes would have been built throughout the world to show experiments from the culture-intercom. “The audience,” wrote VanDerBeek, “Takes what it can or wants from the presentation and makes its own conclusions. Each member of the audience will build his own references and realizations from the image-flow.” Additionally, the urgent utopianism of his project cannot be overstated. He closed the manifesto with the following proclamation: "In probing for the 'emotional denominator,' it would be possible by the visual 'power' of such a presentation to 'reach' any age or culture group regardless of background. There are an estimated 700 million people who are unlettered in the world: we have no time to lose or miscalculate."

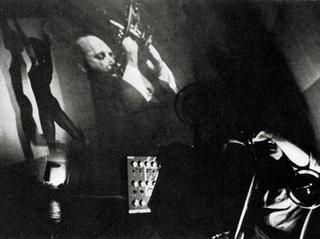

Another Movie-Drome interior.

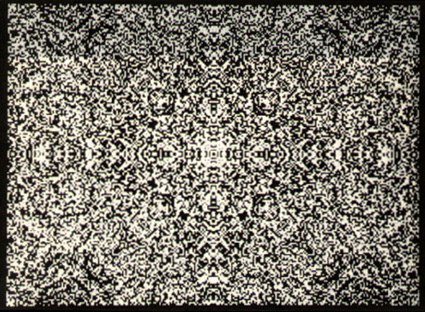

As the years passed, VanDerBeek saw that the image-flow didn’t need to be contained within the Movie-Drome. He made two proposals to NASA in the 1970s. One involved documenting football field-sized letters from space, turning the Earth into a planetary printing-press; the other asked to turn the Kennedy Space Center into an artistic “Center for Inner Space.” Eventually, VanDerBeek was an artist in residence at NASA, a role he also filled at MIT, WGBH (right before Nam Jun Paik), and Bell Labs, where he and Ken Knowlton made numerous complex and pioneering computer films in the 60s utilizing Knowlton’s TARPS programming language and his BEFLIX code, based on punch card technology.

Still from Knowlton & VanDerBeek's Poem Fields

In Expanded Cinema, VanDerBeek explained the thinking behind his many residencies and illuminated the reasons behind of his faith in technological promise:

This business of being artist-in-residence at some corporation is only part of the story; what we really want to be is artist-in-residence of the world, but we don't know where to apply... That's one reason for all these transfer systems... It's a tremendous urgent unconscious need to realize that we can't really see each other face to face. We only see each other through the subconsciousness of some other systems. Cybernetics and the looping-around of the man/machine synergy are what we've been after all along.

VanDerBeek's techno-utopianism got its start at Black Mountain College, the breeding-ground for radical aesthetic innovation with faculty like John Cage, Josef Albers, and Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes provided architectural inspiration for the structure of the Movie-Drome. VanDerBeek’s handmade collage aesthetic, visible both in his early films and the guiding principle of his Culture: Intercom, has antecedents like Eduardo Paolozzi and Max Ernst, and its influence on digital copy-and-paste techniques is recognizable today. His concern with arranging the multitude of existing images has a similar-but-different relationship to ideas and practices by his contemporary Hollis Frampton. VanDerBeek, though, possesses an Age of Aquarius ethos all his own, and his blending of technology and mysticism indicates that he may have more in common with his namesake Brakhage than with Frampton.

True to his holistic style, VanDerBeek opened his lecture at a 1982 conference in Linz, Austria with a dedication to “the intelligence of the extraterrestrial whales,” definite proof that truly nothing remained excluded from his interconnected vision of the moving image-flow.