1.

Around the corner from stacks of baby shoes, counterfeit Gucci wallets, and spangled iPhone cases, I got burned copies of Jean Cocteau's Orpheus trilogy at an outdoor market in Mexico City.

A Sunday afternoon in Roma Norte, I was drinking coffee with new friends. The city was new to me and I had only arrived late the night before. We jumped in a cab and directed the driver to a market a little way outside the center of town.

Miguel said he was going to pick up a copy of Pigsty there. I was confused at first, assuming it had to be something other than the 1969 Italian film, but indeed that was the one he meant. Seemed an implausible feat to find a physical copy of any Passolini movie, let alone a more obscure selection, anywhere without paying for shipping and waiting at least a week. But I didn't say anything then.

"He's not going to find the Passolini film here," Manuel said, as we were wandering through Tepito's labyrinth of tents. It was mostly pirated goods: branded tennis shoes, video games, and handbags; but with some intention to the ordering of the inventory. Suppliers tended to specialize in certain items, one might carry only knock-offs of a single particular designer label, another sold only anime DVDs. Tepito sometimes functions as a wholesaler for vendors who operate smaller streetside sales. We walked through the section that was largely physical media for sale— Blue-ray, DVD, and CDs with covers varying from identical to the original to very handmade-looking inkjet prints. I was told that sometimes you could see vendors burning these disks in the back of the tents.

One of the tents had a sign out front, "Cine de Arte." Inside a dozen densely packed shelves included classic art house fare like 400 Blows, Breathless, Paris Texas, and L'eclisse. Each with a cover made of ordinary printer paper inside a flimsy plastic sleeve.

I was happy to find Bresson's Four Nights of a Dreamer, one of my favorite films. There were loads of Criterion collection burns, an entire shelf devoted to Fassbinder and Herzog. Miguel couldn't find Pigsty, but there were other Passolini films there. Manuel discovered a copy of Jean Luc-Godard's King Lear, with Julie Delpy and Woody Allen. None of us had heard of that one before. It has been a while since I've discovered a film randomly just by my eyes falling upon it, and not through a series of Wikipedia and IMDB-mediated clicks.

Four Nights of a Dreamer is somewhat uncharacteristic of Bresson, lighter and wide-eyed—albeit based on Dostoevsky's short story— about a boy who meets a girl just as she attempts to kill herself. About seven years ago, I rented it from a video store in Chicago where I used to live. Visiting "Cine de Arte" in Tepito made me think of the place and googling later that night, to my surprise, I found it hasn't closed yet. It seems cruel to say, but at the same time inevitable, that just about any physical media film rental operation like a terminally ill patient; you could stop the pain temporarily, or reduce it somehow, but the world is shifting much too rapidly to secure it as viable business model. The economy is already a harsh place for small businesses with their eyes constantly on the margin, and doubly so to those providing services we can do ourselves, not only more cheaply, but also in our own homes.

2.

Halfway between my house and high school, I'd drop in the local video store on my walk back to pick up tapes from the narrow ghetto in the back where all the art, cult, foreign, and otherwise "independent" films were shelved. I burned through the irrefragable alienated teenage classics— Daises, Liquid Sky, Videodrome, Susperia, the rest of that lot. Most of those films I knew nothing about beforehand, and selected only for the cover. Sometimes the cover was what kept me from renting. For weeks, I fretted over the one film I most wanted to see but felt worried about — too embarrassed to take Mike Leigh's Naked home with me. What if my parents found it? Not for the name, but David Thewlis' wanton gaze through the legs of a faceless woman in fishnets on the cover. About ten years passed until I actually watched that one.

That store went out of business a few years ago, marking down everything — the leftover candy and microwave popcorn bags by the cash registers, even the shelves had tags. Each week prices on inventory increasingly slashed. And in the final days of the fire sale it was mainly those art films left. I picked up several for a few dollars each. Some I still have yet to watch.

3.

Things that seem to be just hypothetical copyright possibilities are reality in the globe's farther reaches. A few summers back, I was advised to watch out for certain travel agencies in Hanoi. I often travel alone and generally book independently, but in this case, a number of nearby destinations are regulated as to make it quite difficult to arrange sightseeing without an intermediary. Anyway, the price usually worked out much better than even the cheapest guesthouses listed in Lonely Planet. The warning wasn't just to watch out for scams, but also the high count of tourist drowning deaths in Halong Bay due to improper safety inspections of the junk ships. Best to stick with a reputable agency.

Sinh Cafe was the place recommended to me by a number of people. Trouble was that due to complexities in the licensing of franchises, I wandered through the winding streets in Old Town passing dozens upon dozens of shops with signs that read "Sinh Cafe." A number of lax tourists even mistake the word "Sinh" as Vietnamese for travel (actually it's a nebulous word meaning several definitions of "life.")

I went to the "real" Sinh Cafe to book a few trips. But my tickets to Sapa said "Sinh Tourist." Hanoi won't register trade names of businesses started in Saigon. This means in a sea of Sinh Cafes, the actual Sinh Cafe — the one that has been around for twenty years — doesn't even go by its own name in town to distinguish itself apart from impostors. The owners also failed to register the URL first.

4.

In Vietnam, I took a number of Elle magazine cutouts to dressmakers to replicate in finer fabrics and at lower cost. I bought counterfeit Tiffany's pendants in Bangkok the week before that (packaged in counterfeit robin's egg blue satchels and little blue boxes too.) What's going to happen when Tepito stands in Mexico have 3D printers? I don't expect in my lifetime to print fake Louboutins on demand, but maybe quite soon those Zaha Hadid plastic Melissa shoes could be made under a tent in the outskirts of a faraway city — quickly and cheaply.

Just as suddenly as the digital age dematerialized so many of our things, rapid prototyping seems promising to repopulate the world with objects again— different than what was lost, but things nevertheless. New momentos, new sentimental attachments. These products remind us of the physical and digital world difference, a difference as distinct as awake and asleep.

In Charles Stross' novel Rule 34 — named after that rule — a character wakes up to a rogue 3D printer fabbing sex toys with a porn site URL carved on them. The screen of his computer is alight with spyware for the same site. We can tolerate the salacious popup windows, the offers for "herbal viagrax" in our inboxes because these are digital configurations, and we have the keystrokes and the tactics to evade them in the same fraction of as second as they come to bother us. But human beings must contend with physical objects. (For another example of how the syntax of on and offline may not translate, check out the Idiots of Ants comedy sketch, Facebook In Real Life.)

About the time people were talking about virtual reality, "virtually" was a regular colloquialism for "practically." Practically reality. Now that "practically" is becoming "actually," as the digital artifact untethers itself from digital realm exclusivity, and instead may communicate with us as a physical structures. But the products that come from the ether carry with them the logic of their native territory, as they transition from digital artifact to real world object. The online territory provides a unique mutability, a blend of fictions with reality. "Reality" seems incomplete a word to describe what happens online — similarly metaphors to "space" seems ill-proportioned and IRL-centric.

The Sinh Cafes scattered all over the center of Hanoi seem so much like a living metaphor for what is a way of life on the internet — the duplications, iterations, pirate editions, altered versions of existing things, false identities, network-dependant parallel lives and other machine-oriented mutabilities.

5.

Adding additional— but not unexpected— complexity to contemporary manufacturing bewilderment there is Alibaba, the China-based import-export connection e-commerce site. It counts over 2.5 million storefronts, not just chintz and tat but wholesale for just about anything —construction materials, food stuffs, bicycle parts. Like SEO-scamming made physical, various keywords are thrown in to pick up potential traffic.

Zazzle is another seemingly endless e-commerce site. Users design existing merchandise with their own images and text. Zazzle retains all the prior art, resulting in a odd assortment of baby bibs and coffee cups and trucker hats emblazoned with whatever someone else had thought of — strange slogans, photos of an unknown person's father —and quite often turning up as unexpected Google image search results. It seems like the act of bots, but, writing for DIS magazine, Babak Radboy explained:

Most people on Zazzle are actual people, making products, one at a time, for themselves, as gifts or to make a modest buck. Trolling through Zazzler forums, one reads again and again the hard-learned lesson of techno-capitalism that a hundred terrible shirts invariably will make more money than ten good ones. Here arises a mutant breed of Zazzler—representing a tiny minority of its members but a disproportionately large number of products—marrying the production line and the bottom line with the command line and developing programs that to varying degrees automate their design process, producing tens of thousands of products with little or no human oversight or labor.

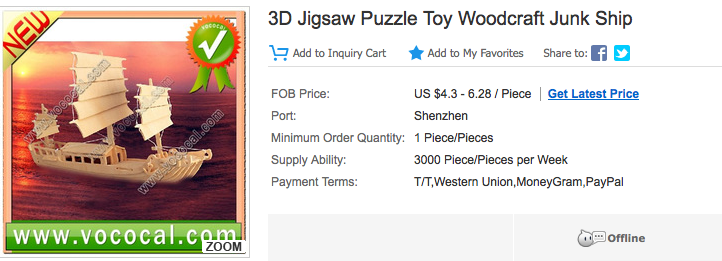

In the middle of writing this essay, I entered "junk ships" into Alibaba's search bar. This delivered a handful of 3D puzzles from Shenzhen. Other words brought about greater variety. "Cephalopod" even directed me to sellers of frozen octopus and cuttlefish.

There may be no reason for that "junk ship" 3D puzzle to ever exist. The product was likely born of reasons other than existing demand. In a boundless e-commerce matrix of key words stacked against everyday objects, untested products pop out with desirability yet to be determined.

The tables turn here, demand responds to supply. But it works. I found what I was looking for, although it was obscure. No one had to speculate whether someone might catch herself nostalgic for Halong Bay's junk ships and then see if some kind of memento existed to acquire after the fact. Alibaba has the potential to be as varied and specific as the world is.

6.

Back in the States I watched the Orpheus series on my laptop. An ad for the company that burned these disks plays before I can access the menu. How funny to think I bought it not at an exclusive place for Wicker Park or Williamsburg cinephiles, but somewhere with mud on the ground, and the smell of smoke and meat from nearby food trucks grilling.

"After years of shameful illegal downloading, I finally decided to go legal," says a recent Yelp review for the Chicago video store I mentioned earlier. But as I recall, much of the inventory was bootleg, only quasi-legal long before people were streaming and downloading. Four Nights of a Dreamer was a terrible copy, an obscure print from Japan or somewhere. Films would show up badly dubbed, with wear and grain from PAL to NTSC translation.

Meanwhile now, there's an approximation of an art video store happening in a Mexico City outdoor market, a destination and community forming around the inkjet printed covers and burned copies of various titles. That wasn't the first time my friends had been to "Cine de Arte," and the other people making purchases there seemed to be regulars as well. The price to keep a tent in Tepito is far less than a stateside brick-and-mortar shop. The same kind of films that were last to go at a suburban video store fire sale are pirated and distributed just like any other blockbuster film. Maybe the owners themselves don't even care about the inventory, it's just that someone wants it at all.

This is the result of our recalibrated sense of scarcity. A new form of limitless capitalism with prices inching, virtually, toward nothing. Anything could exist, and may exist regardless of whether someone wants it. That means availability of pirate Cocteau films with ads for the replicating company and trucker hats with "World's Greatest Dad" printed above a random old man's face. That's why there are junk ship puzzles on Alibaba. Pieces of endless possibilities floating in the ether.