1989 German documentary on Kowloon Walled City (English subtitles, Part 1 of 4)

In Kill Screen, Michelle Young writes about Kowloon Walled City as an inspiration for game level designers. The fortress-like Hong Kong settlement once contained 35,000 residents within its 6.5-acre enclosed space. A labyrinth of alleyways, staircases, and 250 sq ft apartments; much of it poorly lit makeshift spaces with unstable construction; it was also largely a lawless enclave with thriving drug trade, mafia, and other black market activities. It was demolished in 1993:

Often, aspects of Kowloon’s architecture and environment are used to impart a sense of repression, confusion, or loss. In videogames, the mafia and undercurrent of illicit activity provided ideal storylines amidst dank and mysterious backdrops. The cramped businesses in the inner alleys, and the jumbled exteriors of Kowloon, gave videogame designers a rich visual vocabulary.

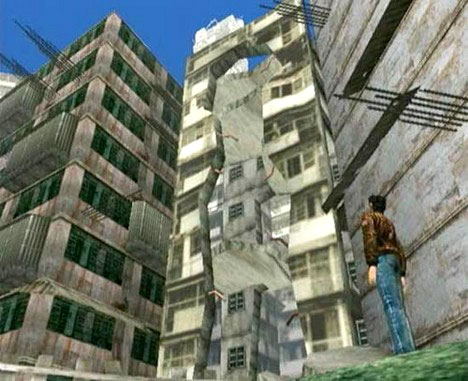

The characteristic that most set Kowloon Walled City apart from other slums was its high-rise, skyscraper form. Videogame design has capitalized on the city’s verticality. In the opening sequence of Shenmue II, we are transported between the normalized architecture of Hong Kong to Kowloon and enter the city as if falling upside-down from the sky into the depths of the Walled City. The distance between Hong Kong proper and Kowloon is greatly exaggerated with hills and wide plains separating the two, likely an attempt to emphasize Kowloon’s “Otherness.”

Kowloon was an anomaly in modern urban construction not only for its organic formation, but also for its reversal of standard building aspects: interior versus exterior, street versus roofs. Its ad-hoc construction engendered a maze of narrow alleys and staircases. Think of single apartment units being stacked over time like Jenga pieces—except that the façades don’t have to be match or be in-line with each other. The network was so vast that it was possible to cross from one side of the city to another without touching the ground once. In essence, the roads were on the roofs and inside the buildings.

The “Kowloon” map in Call of Duty: Black Ops takes advantage of this reversal of streets and roofs by focusing all play on the upper levels of the city. A common experience by players when first playing the map is, “Where the hell am I?” A video DailyMotion goes through the space: “Obviously,” narrator Kevin Kelly says, “This map takes a little bit of time to learn.” Without streets, you traverse over planks, ramps, ladders, rooftops; there’s even a zip-line to take you to the other side of the map. Each building has multiple entrances and levels, and there are many opportunities to fall. At the same time, however, the irregularity of the architecture creates vantage spots for snipers, and nooks in which to hide

...

It is because Kowloon was both real and anomalous that it has captured the imagination of videogame designers. The space lends itself to both highly realistic rendering, as in Black Ops; and mythical spaces, as in Kowloon’s Gate. The real Kowloon City was a place beyond the reach of government regulation until its demolition before the handover of Hong Kong. Perhaps it is only fitting that John Woo’s Stranglehold shows Kowloon destroyed not by the hands of Big Brother, but by the inhabitants themselves, in a continuously crumbling space vulnerable to collapse by Triad gang warfare.

<3 shen mue! nice article too