Corporate Video Decisions, 2011

Corporate Video Decisions, 2011

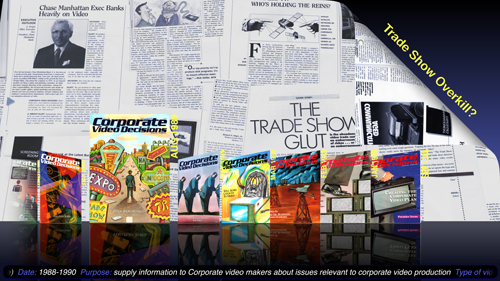

“Corporate Video Decisions,” your current exhibition at Michael Lett gallery in Auckland, includes the covers of Corporate Video Decisions, a magazine from the 1980s about the use of video technology in corporate culture, shown on flatscreen televisions, and a series of printouts of the entire content Diligent Boardbooks’s website, a paperless business software company based in Christchurch, NZ and New York. I’m really fascinated by this double inversion of the way content is communicated to us: the print magazine on monitors, the website printed out. Can you talk a little bit about the exhibition and your use of inversion, as well as languages of marketing and advertisement, as an aesthetic strategy?

Yeah, I should say first that there is another layer of processing that is maybe difficult to make out in the online photos of the exhibition. The print magazine covers were actually photographed playing as jpegs on the LCD 3D-enabled televisions, then that whole image is inkjet printed on canvas, twice—like two copies of each canvas—and these are screwed together with aluminum tubing between the two canvasses in each corner, spaced to mimic the dimensions of the monitor they depict. So you have two canvasses with the same image on top of each other in place of the monitors.

To answer the question, for me, the exhibition’s aim is to present two snapshots of different moments in the recent history of commercial video through looking at these quite different pieces of ephemera—a magazine and a website. The nature of video technology is such that a fast, controlled, obsolescence cycle is systemic to its existence, and materials and formats come and go very quickly. As this is the case, making an exhibition that has this fact built into the way it is presented is for me very important. That is to say, the way the content is presented should form a dynamic which helps describe the show’s themes. Depicting the fickle material conditions of video via changing formats of what is regarded at a certain moment to be contemporary ephemera (magazines, websites), which are then presented through another fast shifting technology (printing), one indicates these movements in the presentation structurally.

Contrasting this ephemerality with the themes that are covered in the 80s magazine—trade fairs, gender and minority equality, economic conditions, crisis culture, generic products—(these topics clearly relate very well to our current moment also), underlines the truism that while technology might change, certain issues tend to be relevant for longer periods.

For me the exhibition’s format highlights this tension between the permanent and the impermanent, between vast material change and comparatively slow shifts in life/work conditions.

On the language of advertising, one has of course this ambivalent relationship to it where one knows it’s manipulative, but its efficiency is seductive and affective. One most likely follows this language’s logic implicitly in one’s self. That is to say this way of communicating is unavoidable and is just there. I am not sure if looking at this is really an aesthetic strategy. Even just conversing can be considered to be a commercial act, and it’s not so easy to attach a value to this. It is one’s life, after all.

Disruption and modification of the commonplace visual experience form a large part of your work, from superimposing images from television woven onto towels to the printing out of a website. In Negative Headroom (2010), you look into a historical event—a famous instant of transmission piracy where a hacker disrupted two broadcasts of “critical” television host and Coca Cola endorser Max Headroom in the 1980s. What do you think are the possibilities that these disruptions offer? How do they change the way we think about information and the channels through which we get it?

With presenting objects and images in translated forms I want to bring certain moments into focus in one place and time that were relevant in another. The Headroom piracy incident was a beautiful “feedback” moment in network TV, a system that is/was problematic in part because of its one-way broadcast from center to margins. In one sense, the hacker dressed as Max Headroom foreshadows a YouTube answer to this problem, in another sense it celebrates intervention just for the sake of it, pranksterism. I thought this was an incident that would read well if eulogized in an exhibition format. I chose to present images and objects that underlined the aspects of this incident that I found relevant. This material was not all deriving directly from the incident, some objects I felt related in less direct ways—for example, I included an entire shop display for a new Samsung TV, which in the last week of the exhibition, was unexpectedly stolen from the exhibition venue, folding back on the logic of my presentation. The how is the what, right? So this is where disruption and modification come in—it’s a big part of the grammar available when relaying information through objects. Information always comes through an experience of some kind, so it’s about what tone a certain experience might bring to some information one is trying to present. One example of how this plays out is the fact that the project involved similar presentations in three very different venues—at a small German kunstverein in Lüneberg, Art Basel Miami, and the Contemporary Art Museum St Louis, which certainly highlighted this idea.

The works in your 2009 exhibition “Deep Sea Vaudeo” call attention to the television screen as an object and consider the current disappearance of CRT televisions and the move to LED screens. In “Aquarium Paintings,” your exhibition with Nick Austin in Berlin, you presented an inversion of Austin’s paintings into videos. Your installation works are dense and very material. For someone who deals a lot with digital culture and ideas around it, you seem to be very interested in objects and the objects digital culture left behind. Is that so?

Yes, for sure. When making exhibitions physical concerns are always central. “Digital culture” is also obviously not immaterial. For me, it’s so much about what this kind of culture leaves behind, it’s really about the stuff that culture is made of. Part of what I am interested in is reinforcing the relationship between the objects that are used within this cultural framework or series of systems, with the structures and content that flows through those objects. Objects in this way can operate as placeholders for certain moments in time.

You seem to consume enormous amounts of information that you then repurpose, modify, or edit as part of your works and the texts accompanying your exhibitions. With appropriation being such an important component of your work, what is your approach to intellectual property, creative commons, and ideas of authorship?

This is obviously really complex, something I am apprehensive to say something definite about. These are clearly societal issues that not only have an impact on the cultural field but also—most obviously—on politics and economics. I am a big admirer of the creative commons effort. I also think that particularly in a strictly legal context intellectual property appears to me as a very murky field. I can say more experientially that it seems to me that we are at a moment in time where making strict authorship distinctions seems sort-of forced, counter to how life functions. It’s very tempting to think that if an idea enters one’s mind it is a part of you and therefore on a human level as much yours as the property of its source. This logic feels a bit like logic I’ve heard in arguments in favor of graffiti—where the legal position is even clearer. The constant process of recognizing things and understanding things we all have to go through to live seems to me a process very close to aurthorship. To come into contact with something is in a way to create it and I think this is instinctually where my very loose approach to these matters in my work begins. At this moment, as an artist, I act without a clear structure of how to deal with these issues.

Age:

28.

Location:

Berlin.

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

No reply.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

At art school.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

University of Auckland in the Fine Arts Department in Auckland, New Zealand and then at the Staedelschule Hochschule fuer Bildende Kunst in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. I studied visual art.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

I don’t totally identify with those divisions. But if I get what you mean, in those terms I use a range of media, both traditional and more recent. Depends on the project what the format becomes.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

Yeah, I like to go to a range of things often esp. where I live. Hard to draw a line…

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I was once a fulltime librarian. I still look to libraries a lot.

Who are your key artistic influences?

No reply.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

I was part of two collectives when I lived in Auckland, Special Gallery and later Gambia Castle. We worked to make it possible to make what we considered worthwhile exhibitions happen where we were living. I have recently put on a number of parties with my friend Yngve Holen. Often they have been staged around using photocopiers in place of disco lights.

Do you actively study art history?

Yes

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

Yes. My interests change…

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

Sure. My interests are touched on earlier.