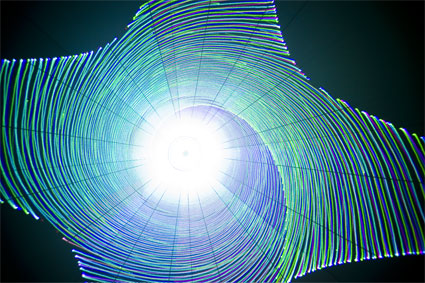

Installation view at FACT (Foundation for Art Creative Technology) Photographer: Stephen King

Nam June Paik (1932 - 2006) is an artist fabled for what he has achieved, as the instigator of video art, the pioneer of media art and through his influence on the indebted MTV generation. It's as if his career is almost made for the retrospective exhibition. His work is bound to his legacy, and his influence is hard to encompass. The importance of this legacy asks two parallel questions, how to preserve, present and document but also how to react, trace and respond. Both are targeted through a new joint exhibition of Paik's work at Tate Liverpool and FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), the first major retrospective of his work since his death in 2006 and the first exhibition of his work in the UK since 1988.

Tate presents a comprehensive chronicle of Paik's movements through the avant-garde, in performance, composition, television and sculpture. There are TV sets, robots and Buddhas, mixed with historical documentation, vitrines filled with exhibition programs, posters and photographs and timelines drawn on walls, which denote his many collaborators and read like a roll call of the most influential artists of the 20th century - John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Joseph Beuys and Merce Cunningham.

In contrast to the Tate, where you can look and listen with historical meticulousness, at FACT you are given a remote control. Here you are encouraged to relax, in an archive lounge, and browse a collection of his video works at leisure. Or lie back underneath Laser Cone (1998) and be dazzled.

The show’s split nature, across two venues, pays tribute to the very legacy that it seeks to explore. In some ways, FACT, as an organization that has grown over the last 20 years through commissioning and presenting new media and video, is indebted to Paik’s original exploration of new technologies.

Nam June Paik’s story is played out right through the exhibition. Born in Seoul, Korea in 1932, he studied art, philosophy and composition in Japan and Germany. Later, he was greatly influenced by encounters with John Cage and George Maciunas, from whom he took up the fluxus agenda. He made one of his earliest video works in the shop where he bought the first portable video recorder, the Sony Portapak. He shot a simple fluxus action, buttoning and unbuttoning his shirt. He also paid homage to Cage’s 4’33, in Zen for Film, a silent, 8-minute, blank film.

Through his meditations on the potential elegance and grace of the video medium, Paik embraces and plays with nature, from simply placing a magnet on top of a television to representing various natural forms on screen.

Egg Grows, No. 4 (1984) is a sculpture made of a live video of an egg, replicated on 8 individual monitors, each placed next to a monitor of greater size. The on-screen eggs get scaled up and angled over at each repetition. This simple and coherent setup is mirrored in the mesmeric, One Candle (1989). The fleeting image of a candle flame is produced by three projectors, all running off the same video camera pointed at a burning candle. The red, green and blue light of the projectors shows ephemeral flickers of candle flame as it slowly burns itself out. The spiritual quality of the work reflects Paik’s interests in Zen Buddhism, evident in much of his work. His drive towards beauty is enhanced by the dichotomy of the real flame and the projected image. The three very large, now obsolete projectors look like giant boulders propped on the floor and create an amusing contrast of scales with the small and delicate candle flame.

Photo: Helge Mundt

Paik is most successful in expressing the beauty of the video medium in his Moon is the Oldest TV 1965 (1992 version). Paik created a transcendental space, an installation in a backed out room, only lit by light emitted from eleven televisions, arranged on plinths, in an arc. The group of screens flow across the back of the room, each filled with an image of the round moon. As an object of continuous human obsession and gaze, the moon serves well to illustrate Paik’s mastery in harnessing the potential of the video image and taking the television screen into undeveloped territory. The televisions themselves fade into the darkness of the space and all that remains is the haunting light that they emit.

Like his close collaborator, Joseph Beuys, Paik deeply believed in the power of art to positively influence society. He possessed a potent vision of the potential of video as essential democratic media with the ability to unite and connect people. On New Year’s Day 1984, Paik presented the first international satellite installation to over 25 million viewers, linking New York, Paris, Germany and South Korea. Good Morning Mr Orwell (1984) was something of an avant-garde art variety show featuring Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, Merce Cunningham, and Charlotte Moorman with her and Paik’s TV Cello. For Paik, it was a response to Orwell’s dystopian vision of the use of totalitarian television control in 1984. His spirit and enthusiasm for connecting communities follows through his trademark vivid, cut and paste, slash edits and video synthesis.

For all the glowing, vibrant light and color often on show, it is a quiet, muted object that sits in the center of the gallery at Tate that gets to the heart of Paik’s legacy and purpose. Rembrandt Automatic (Rembrandt TV) (1963/1976) is a television set resting on its screen. The television, face down, becomes an alien object; its function stripped, unnatural and ambiguous. The muted form is left with no content but the brand name visible on the back, titled, Rembrandt Automatic. It resonates further in the historical context of the works shown at Tate, where the age of the equipment originally employed by Paik adds a retro appeal. The rates at which the objects take on obsolesce and a museum piece quality is very evident. This collision of art and technology, a chance object, exemplifies what Paik achieved so brilliantly, he was a champion and conqueror of the everyday, right from his fluxus roots to his laser extravaganzas, he foresaw a future of technology that was ubiquitous and fantastic, as he wrote, “without electricity, there can be no art.”

Peter Merrington is an artist and writer currently based in Liverpool.

Great Article!

Love the commentary and the pictures (especially the egg one) are awesome.

Just signed up to rhizome and can't believe I just found it.