An excerpt from Take This Book: The People's Library at Occupy Wall Street, an extended essay by Melissa Gira Grant, forthcoming in print, epub, and as a Kindle single. Available to support on Kickstarter.

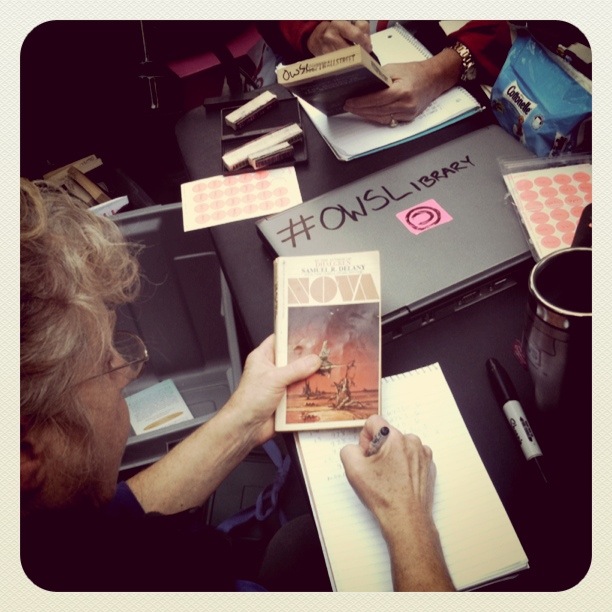

Instagram Photo by Melissa Gira Grant

Remove everything but the books. The librarians who were most versed in direct-action tactics—from participating in various peaceful and spirited disruptions, at street protests against the Republican National Convention in New York in 2004, or while bringing cheer to Wall Street police barricades as a roving brass band—had worked out a plan for what they would do in case of a raid. Whoever was in the library would grab the laptops, the archives, the reference section—countless signed editions among them—and ferry them to safety.

"Philosophically," Jaime, one of the librarians, said, "the books stay with the occupation."

There had been a dry run, too, the night the Occupiers prepared for the city to evict them. On October 13, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that Brookfield Properties, which legally owned the park, wanted to clean Zuccotti, and the Occupiers anticipated that the mayor would also send in the New York Police Department to remove them. So the Occupiers took this order both graciously and defiantly: They would clean the park themselves, and early in the morning, when the cops and the cleaners were to arrive, the Occupiers would refuse to leave. Someone posted an invitation to Facebook on the day of the cleanup, calling people to gather before Wall Street's opening bell, and to bring brooms and mops and pails. All day, wearing ponchos and latex gloves, Occupiers scrubbed the stone steps of Zuccotti, swept the grounds, and straightened their camp's stations. As night fell, some of the camp's infrastructure was evacuated: most of the Kitchen, the Media Center, and almost all of the sleeping bags, foam mats, and blankets that people weren't using at that moment, and at that moment, the moment I entered the park, just after two in the morning on the day we'd been told we'd be evicted, a dozen or two people were still curled up on mats, plastic tarps drawn over their faces, in the swells of rain that joined us as we arrived in the park, that took us down the clean stone steps leading to Broadway, and that ran two-inches deep and quick, into my boots and into the blankets of the few people still trying to sleep.

But near those stone steps, just off to the north side of the park, along Liberty Street, was the library. It was still there, raised up on clear plastic bins, taped over with tarps covered in slogans. That afternoon and into the night, a librarian named Stephen Boyer prepared it: lining up the boxes and taping down the tarps. If someone had slashed into the plastic, she would have seen yards and yards of books, lined up in their clear plastic bins, and there would be no doubt that what she had discovered had been ordered, taken care of, and if doubt still remained, then there was the poetry written on the tarps, too.

The covered-up mass of the library stretched at least 20 feet in length, five or so feet high, a dull-blue mound gleaming with rain that sheltered those of us sitting beside it. There was the woman with the ash-blond curls and the good boots and trench coat, a media badge around her neck, who, each time I looked up at her over the course of hours, could be found rolling a cigarette on the top of her suitcase. There were the three of us—my protest pals for the night, Darryl and Joanne —talking and pacing and inadvertently sleeping on the stone bench set into the wall along Liberty, which was where I always told people who were coming to the park for the first time to meet me. We didn't talk about where we were going—I just led us there, and we sat. Darryl had two onions in his canvas tote bag because when he had been in Tahrir Square that summer, he had learned that if they use tear gas against you, you should bite into an onion to counteract the gas. Every 10 minutes, I thought I might throw up because nobody knew if or when the cops were coming, how many there would be, how they would move or remove us. So that was how I ended up spending hours in the library, with the library, and woke from a soft sleep around half past four as someone called out Mic Check! and asked for help carrying the library to a van parked down Broadway. I don't know how many hands came forward to do it, but the transfer was done in just a few minutes and then nothing but a corkboard was left on the stone bench where the library began.

"Philosophically," Jaime, one of the librarians, said, "the books stay with the occupation."

There had been a dry run, too, the night the Occupiers prepared for the city to evict them. On October 13, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that Brookfield Properties, which legally owned the park, wanted to clean Zuccotti, and the Occupiers anticipated that the mayor would also send in the New York Police Department to remove them. So the Occupiers took this order both graciously and defiantly: They would clean the park themselves, and early in the morning, when the cops and the cleaners were to arrive, the Occupiers would refuse to leave. Someone posted an invitation to Facebook on the day of the cleanup, calling people to gather before Wall Street's opening bell, and to bring brooms and mops and pails. All day, wearing ponchos and latex gloves, Occupiers scrubbed the stone steps of Zuccotti, swept the grounds, and straightened their camp's stations. As night fell, some of the camp's infrastructure was evacuated: most of the Kitchen, the Media Center, and almost all of the sleeping bags, foam mats, and blankets that people weren't using at that moment, and at that moment, the moment I entered the park, just after two in the morning on the day we'd been told we'd be evicted, a dozen or two people were still curled up on mats, plastic tarps drawn over their faces, in the swells of rain that joined us as we arrived in the park, that took us down the clean stone steps leading to Broadway, and that ran two-inches deep and quick, into my boots and into the blankets of the few people still trying to sleep.

But near those stone steps, just off to the north side of the park, along Liberty Street, was the library. It was still there, raised up on clear plastic bins, taped over with tarps covered in slogans. That afternoon and into the night, a librarian named Stephen Boyer prepared it: lining up the boxes and taping down the tarps. If someone had slashed into the plastic, she would have seen yards and yards of books, lined up in their clear plastic bins, and there would be no doubt that what she had discovered had been ordered, taken care of, and if doubt still remained, then there was the poetry written on the tarps, too.

The covered-up mass of the library stretched at least 20 feet in length, five or so feet high, a dull-blue mound gleaming with rain that sheltered those of us sitting beside it. There was the woman with the ash-blond curls and the good boots and trench coat, a media badge around her neck, who, each time I looked up at her over the course of hours, could be found rolling a cigarette on the top of her suitcase. There were the three of us—my protest pals for the night, Darryl and Joanne —talking and pacing and inadvertently sleeping on the stone bench set into the wall along Liberty, which was where I always told people who were coming to the park for the first time to meet me. We didn't talk about where we were going—I just led us there, and we sat. Darryl had two onions in his canvas tote bag because when he had been in Tahrir Square that summer, he had learned that if they use tear gas against you, you should bite into an onion to counteract the gas. Every 10 minutes, I thought I might throw up because nobody knew if or when the cops were coming, how many there would be, how they would move or remove us. So that was how I ended up spending hours in the library, with the library, and woke from a soft sleep around half past four as someone called out Mic Check! and asked for help carrying the library to a van parked down Broadway. I don't know how many hands came forward to do it, but the transfer was done in just a few minutes and then nothing but a corkboard was left on the stone bench where the library began.

We're talking about projects we want to work on

Check out this video on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K56soYl0U1w&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Sent from my iPhone

Nice share