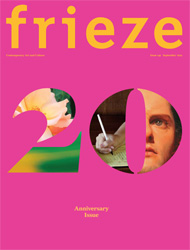

Frieze has a massive new issue out celebrating its 20th anniversary with contributions from Bruce Sterling, Lynne Tillman, Kazys Varnelis, Simon Critchley, and Nina Power. Rhizome executive director Lauren Cornell also has an essay in the new issue:

Since 2005, I’ve been the director of the online organization Rhizome, and have spent a considerable amount of time thinking about why ‘Internet’ is such a gauche word in contemporary art. Here are a few simple reasons I’ve come up with. First, medium-specificity is out of style and the word ‘Internet’ suggests a medium – something separate, something cyber – even though the term can really be used now to describe the experiences that come with an expanded culture and communications system, not just its underlying network protocols. However, this perception of the Internet as a separate artistic territory persists, with its roots planted firmly in the 1990s. In step with Clinton-era rhetoric around globalization, and excitement for new information technologies, the first Internet bubble swelled in the ’90s and burst in the early 2000s, as did patience with ambitious but under-resourced ‘net art’ exhibitions (read: faulty browsers and error signs). Quickly, it was all but abandoned by the art world save for a few ambitious museum media lounges. It’s important to note that much of this ’90s-era ‘net art’ was preoccupied with the technology itself, not with celebrating it, but considering and subverting it. This focus made it somewhat impenetrable for the non-technologically inclined and challenging to exhibit off-line. In the last few years, however, the field of art engaged with the Internet has expanded to being both about new tools and simply how we live our lives – the humanity on top, so to speak.

A second reason for the slow response is that, unlike other industries, such as music and publishing, the art world wasn’t forced to react to cultural shifts wrought by the Internet because its economic model wasn’t devastated by them. The quality of Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010), for instance, isn’t dependent on YouTube votes or the extent to which it circulates virally, and nor can one download and install a BitTorrent of a Rachel Harrison sculpture. The principles that keep the visual arts economy running – scarcity, objecthood and value conferred by authority figures such as curators and critics – make it less vulnerable to piracy and democratized media. The difference between these models belies a more fundamental opposition in values that might give us a third and final reason why the art district and the Internet are polarized: broadly speaking, the art world is vertical (escalating levels of privilege and exclusivity) whereas the web is horizontal (based on free access, open sharing, unchecked distribution, an economy of attention). Furthermore, technology is bound to what we could call a Modernist narrative of cultural progress, innovation and mastery, whereas art is no longer tied to this model. As the artist Michael Bell-Smith put it: ‘Technology is about fixing problems, art is about creating them.’

These points describe positions that have begun to break down. By now, every kind of artistic practice has been touched by the Internet as both a tool and as something that affects us in a broader sense...