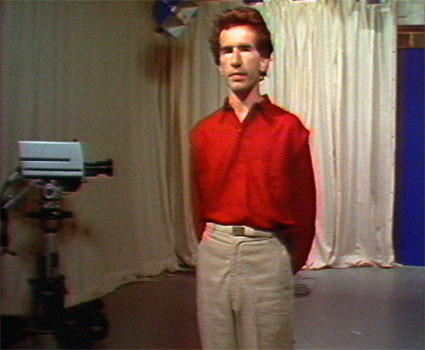

(Courtesy the estate of Stuart Marshall and LUX, London)

Britain, under the Conservative government in 1974, slowed to a government-mandated three-day week: not an immense gift of extended vacation, but a foreshortening of the working week based on the amount of electricity available. From January to March of that year, businesses, shops and services were only open for three consecutive days, and television companies were forced to end their broadcasts at 10:30pm. The remarkable visibility of this retrenchment is perhaps an apposite introduction to the fiscal circumstances of Britain at that time, as it was counterbalanced by extreme activity in the visual arts, with a burgeoning moving image practice taking place in various underground clubs and cooperatives in London and other regional centers, and mainstream television ("mainstream" being redundant; except for some regional variations, there were only three channels at the time) airing artists’ film and video, primarily on Channel 4, which was established in 1982.

This is the period revisited by Raven Row’s current show "Polytechnic" - the late 1970s and early 80s, when artists began using the new medium of video to reflect upon and deconstruct codes of representation, politics and social mores. It’s a smart and striking choice for an exhibition, as the legacy of this time is ambivalent and is still in the process of being settled: art-historically, it’s been partially eclipsed by what preceded it (the medium-specific investigations associated with the London Film-Makers’ Co-op) and by what followed - that is, the yBas, who pretty much turned around and rejected the commitment to politics, collective production and art as labor (not commodity) that this group stood for. At the same time, many of the artists included in the show - Catherine Elwes, Susan Hiller, Ian Breakwell, Stuart Marshall - went on to teach in various art schools (many of them former polytechnics, hence, perhaps, the title) and showed their work on Channel 4 during the 1980s, meaning they have had a much more dispersed, though less visible, impact on art and the wider sphere of culture. Have had and have: Elwes, for example, has recently founded a journal devoted to the moving image (MIRAJ), so the territory contested in this earlier period continues, to a certain extent, to be contested.

(Exhibition view, Raven Row, Courtesy the artist, Photograph by Marcus J. Leith)

Moving away from the Structuralist films of the 1960s and early 70s, these works returned to a representational language and, as curator Richard Grayson notes in his catalog essay, to "narrative" (or perhaps more broadly, to content), an argument that provides the guiding thread through the different works on exhibition here. The works themselves are acerbic, dissatisfied and incisive. Stuart Marshall’s video The Love Show (Parts 1-3) (1980) addressed societal roles and the various stances of authority by which television constructs and ratifies them - including, most memorably, the latent hysteria behind children’s program presenters (an attractive female presenter speaking in dulcet tones: "The only sure way of staying alive is not to do what that child did"). Love Story Part 3 shows the power dynamics, akin even to sanctioned rape, of a man asking a woman he does not know for a drink. Two actors enact the scenarios in a television studio, while a narrator (the woman under threat) decodes the behavior on display, explaining that the freedom of the woman is foreclosed when the man opens the car door for her to enter without asking her if she wants to get in. Meanwhile in the video Kensington Gore (1981) Elwes, who worked as a make-up artist on BBC dramas, interweaves a story of a woman who had an accident with the application of paint onto an actor’s neck for a fictional slasher drama, contrasting modes of linguistic and cinematic construction of events. In We Have Fun Drawing Conclusions (1981) Steve Hawley lampooned the popular British children’s book series where Peter and Jane do "normal" activities that "all children like." The production of gender norms ("All boys love cars. All girls help mummy. Look what a good girl Jane is!") is almost too obvious to need pointing out, but perhaps we have films like this and a thirty-year interim to thank for that.

Deconstruction of the production of illusion and acknowledgment of the manipulation of spectatorship - Post-Structuralism and the different strands of 1970s film theory, such as the work of Laura Mulvey, were great influences at the time - were both the methods and the subjects of these videos, and language and humor, as so often is the case in Britain, were key to their argumentation. Indeed, despite the importance of specific context to these works, what seems most notable is their participation in the longstanding British tradition of satire - one more literary than visual, and one in which moralizing stances are both proffered and taken away, or both praised and shamed. The quintessential British trope of authority undone by a breakdown in communication - the shopkeeper who can’t understand his customer ("Fork handles?" "Four candles!") in a famous comedic sketch - is as symptomatic of deconstruction as of a literary tradition that the return to a narrative approach perhaps here facilitated. The protagonist of John Adams’s Sensible Shoes (1983), in which a woman is trying to tell a story of a love affair but keeps getting distracted by what’s on TV - a canny collision of home recorder technology and public broadcast technology - is a strong addition to literature’s cast of hopeless heroes; David Critchley’s Pieces I Never Did (1979), here displayed as a three-monitor installation, shows the artist speaking to a camera, as if in a memoir, about the works he says he never made. As though paralyzed by his surfeit of ideas, the artist speaks from the position of authority that a man with a camera trained on him enjoys - an irony made all the deeper by its sheer fiction: by naming the works, of course, Critchley in fact makes them.

However, for once with Raven Row’s ample set of galleries I wished to see more pieces, and I struggled a bit to see the argument running through the exhibition, which hung uncomfortably between survey and personal selection; more proof, perhaps, of the ways in which the works are still negotiating their relation to their historical and present context. The last work in the show, chronologically, is Ian Breakwell’s Continuous Diary (1984), one of a series of complex video-essays that combined hand-written notes, images and ephemera that he made in the 1970s and 80s. This 1984 iteration was commissioned by and was aired on Channel 4, a medium whose contributions hover here as the next chapter to be more publicly and extensively explored.

Melissa Gronlund is the managing editor of Afterall journal and Afterall Online. She is a programme advisor to the artist's moving image section of the London Film Festival.

Q: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8KJ2mYBn8FU

A: http://www.emvergeoning.com/?p=6414#comment-208421